Hope, love, commitment and communal responsibility echo throughout their lives and work, and are woven into all they say and do. Hope for the planet; love for God, neighbor and all of creation; commitment to reducing energy use and fossil fuel consumption; and responsibility for each other and the earth.

The six people, one faith-based environmental organization and two congregations on these pages are working daily to care for creation. They have different concerns: some focus on local projects that build community; others fight shale gas hydrofracturing and the Keystone Pipeline; while still others teach, write and train others into action.

But the driving force behind all their work is an activism that has been shaped by faith.

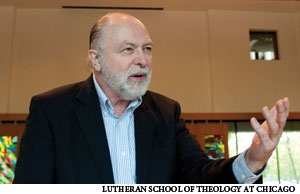

“Caring for creation is a vocational effort to love and restore creation because it is the right thing to do,” said David Rhoads, director of the grassroots environmental organization Lutherans Restoring Creation (LRC) and professor emeritus of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC).

“Caring for creation is a vocational effort to love and restore creation because it is the right thing to do,” said David Rhoads, director of the grassroots environmental organization Lutherans Restoring Creation (LRC) and professor emeritus of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC).

“I’m motivated not by accomplishments or even by any assurance that what we do will ‘work,’ but by the grace and love of God so present everywhere in creation,” he added. “We need personal and social transformation.”

David Rhoads is director of Lutherans Restoring Creation, a grassroots environmental organization that provides resources to the church, congregations and outdoor ministry sites.

Rhoads has lived these words since 1998 when he started a group that works to develop LSTC as a green seminary. He also had a hand in creating the ecumenical Web of Creation and The Green Congregation Program, which provide workshops and resources for churches interested in “greening” their church. Now, as LRC director, he oversees its operations as a clearinghouse of environmental resources and networking for the church.

LRC hosts the Energy Stewards Initiative, an online platform that assists congregations and camps in reducing their energy usage and carbon footprint, and offers a website providing worship resources.

Rhoads, a member of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, Racine, Wis., was drawn to this mission because he believes we are in deep trouble as a planet. “Since I began this work, I’ve studied global climate change, air pollution, land degradation, waste, deforestation, overpopulation, freshwater depletion, among others. Learning about these crises we face has sobered me and made me more committed,” he said.

Jim Martin-Schramm, professor of religion at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, has been active in sustainability initiatives on campus since 1993 when he arrived there to teach.

Jim Martin-Schramm, professor of religion at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, has been active in sustainability initiatives on campus since 1993 when he arrived there to teach.

Luther is a charter signatory of the American College & University Presidents Climate Commitment, which requires sustainability to be part of every student’s learning experience and seeks eventual carbon neutrality on campuses. Luther’s goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2015, by 70 percent by 2020 and to be carbon neutral by 2030.

Jim Martin-Schramm stands by one of the blades for Luther College’s 1.6 megawatt GE wind turbine that he was instrumental in bringing to Decorah, Iowa.

Martin-Schramm, a member of First Lutheran Church in Decorah, also chairs the boards of Iowa Interfaith Power & Light, a multidenominational group working for the planet, and the Winneshiek Energy District in Decorah. Both organizations champion energy efficiency and renewable energy as strategies to reduce climate change and promote a more sustainable and prosperous future.

“I believe we all share one vocation — the care and redemption of all that God has made,” he said. “The unconditional love of God frees me to pursue this. I can do so knowing that, as imperfect as our efforts may be, they are still worthy in the eyes of God.

“The love of God cannot be separated from love of neighbor. Our neighbors include those near to us as well as those far away both in terms of distance and time. Climate change poses unprecedented threats to future generations. My Christian faith calls me to do all I can to defend their interests.”

After reading Frances Moore Lappé’s book Eco-Mind: Changing the Way We Think, To Create the World We Want (Nation Books, 2013), the earth stewardship group at Faith Lutheran Church in Leavenworth, Wash., was deeply moved.

After reading Frances Moore Lappé’s book Eco-Mind: Changing the Way We Think, To Create the World We Want (Nation Books, 2013), the earth stewardship group at Faith Lutheran Church in Leavenworth, Wash., was deeply moved.

“We realized God was calling us to take concrete, hope-filled action to embody care for creation in our community, including prayer and worship, recycling, gardening and more,” said Barbara Rossing, a member of the congregation and professor of theology at LSTC.

Although its members have been active in environmental issues since the 1970s, this group has only been working together for two years. Among its accomplishments is the installation of a 96-panel community solar project on the middle school that powers the school and homes of residents who buy shares in the project.

Members and friends of Faith Lutheran, Leavenworth, Wash., gather to dedicate one of the congregation’s major accomplishments in caring for the earth — solar panels that power a school and homes.

“Solar panels are a visible sign of the church’s commitment to a vision of hope for the future of the world,” Rossing said. “We are making a small but important step to help our economy transition away from fossil fuel-dependence, a vital energy shift reflecting our love for God’s people and all creation.”

The earth stewardship group’s next project is to make “eco-Reformation” a part of the 2017 anniversary of the Reformation.

The collective effort is essential to Rossing: “Without Christian community, I would despair at the enormity of the problem. But I see what faith and prayer and determined action by people of faith have accomplished together, such as ending slavery and other injustices.

“Like the earliest Christians in the Bible, we support one another in sacramental community, proclaiming God’s grace through joy-filled action and bold testimony. Faith gives us hope, through the communion of saints, including saints across the generations.”

A member of St. Peter Lutheran Church in New York, N.Y., Pat Almonrode came to eco-activism through a gradual and nonreligious conduit.

A member of St. Peter Lutheran Church in New York, N.Y., Pat Almonrode came to eco-activism through a gradual and nonreligious conduit.

When he became concerned about climate change some five years ago, he started signing petitions and making donations. Then he joined 350NYC, the local affiliate of 350.org, a grassroots network of volunteer-run campaigns in more than 188 countries working to solve the climate crisis.

“It was the proposed Keystone Pipeline, however, that got me up out of my chair and out into the streets,” he said.

In his efforts to save the planet, Pat Almonrode (left), pictured with Fletcher Harper of GreenFaith and Elizabeth Ackerman of Riverside Church in New York, helped organize the People’s Climate March last fall.

The facts of the pipeline disturbed him greatly: “Oil from the tar sands is the dirtiest in terms of the cost of extracting it and its very high carbon intensity. If built as originally planned, it would have crossed the Ogallala Aquifer, which provides drinking water to millions of people and irrigates the country’s breadbasket.”

Due to his activism against the pipeline and involvement in the environmental committee of the Metropolitan New York Synod, Almonrode helped organize the People’s Climate March last September.

Currently he’s working to strengthen the connection and collaboration between his groups and the allies that came together for that march. “When we came together for the People’s Climate March, the varied interest groups, like those advocating for tenants’ rights and the homeless, came out of their silos and recognized the commonalities shared between our issues,” he said.

Almonrode’s activism is now tied deeply to his faith: “I want to make a genuine response to the gift of creation and [my] salvation. I want to help people realize we have to love each other and we have to love the world.”

While growing up, Leah Schade experienced God’s presence in the forests of Pennsylvania as much as in church. But she couldn’t find a way to express her distress over environmental desecration until called to pastoral ministry.

While growing up, Leah Schade experienced God’s presence in the forests of Pennsylvania as much as in church. But she couldn’t find a way to express her distress over environmental desecration until called to pastoral ministry.

“It was the arc of my theological awareness and sense of call to ministry that gave language to what I witnessed and the change I wanted to bring about,” she said.

Schade started an eco-ministry committee 10 years ago in her first congregation and more recently became an advocate and activist for environmental issues ranging from hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to clean air standards. She was also part of a successful attempt to defeat a proposed tire incinerator in her community of Milton, Pa.

Besides serving as pastor of United in Christ Lutheran Church in West Milton, Pa., she teaches courses and workshops in preaching, ecology and ethics and is an adjunct instructor in religion and philosophy at Lebanon Valley College, Annville, Pa.

In her ministry of environmental advocacy, Leah Schade has become a “fracktivist,” taking on the industry at such places as this drill rig in the Tiadaghton State Park in Lycoming Country, Pa.

In her upcoming book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology and the Pulpit (Chalice Press), her goal is to “show how preaching can help give new life to God’s earth, and that God’s earth can give new life to preaching.” One goal of the book is developing a Lutheran eco-feminist Christology for preaching.

Environmental activism outside of the congregation is important to Schade, such as her service on the Upper Susquehanna Synod’s task force examining justice issues around shale gas drilling. This bipartisan group is made up of pastors, theologians, teachers, lay leaders, scientists and individuals who either worked in the industry or were favorable toward it.

After more than two years, they were able to agree that exemptions from regulations enjoyed by the fracking industry were unjust.

“In 2014 our synod assembly voted to ask our legislators to close the so-called ‘Halliburton Loophole’ and put the industry under the same laws as everyone else,” Schade said. “Fracking threatens water, air, public health and contributes to climate change. It is the ‘perfect storm’ of environmental devastation. Faith is absolutely essential to this work because it can be very depressing facing the devastating realities of ecocide.”

Larry Rasmussen, professor emeritus of social ethics at Union Theological Seminary, New York, N.Y., has harbored deep concerns for the environment since the early 1970s during the first energy crisis. Then he was already teaching a course in environmental studies, energy and ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, D.C.

Larry Rasmussen, professor emeritus of social ethics at Union Theological Seminary, New York, N.Y., has harbored deep concerns for the environment since the early 1970s during the first energy crisis. Then he was already teaching a course in environmental studies, energy and ethics at Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, D.C.

Rasmussen’s interest has not waned: “I’m passionate about this because all of us together have to find a way through the high-stakes standoff between the global human economy and nature’s economy. We’re wrapped in a contradiction of our own making: the human economy needs to expand to continue growth, but that same economy needs to contract in order to prevent catastrophic climate consequences.”

Larry Rasmussen

He has lived these words by being involved in faith-based environmentalism with the World Council of Churches, in his community and in congregations.

Among his nine books is Earth-Honoring Faith: Religious Ethics in a New Key (Oxford University Press, 2012), which earned the 2014 Nautilus Gold Prize for the best book in the ecology/environment category. He leads a decadelong project of the same name that meets yearly to focus on environmentally based themes.

Regarding the conundrum of the human economy versus the environment, he asserts, “Either we change the economic model or we change the laws of nature. Since we cannot do the latter, how are we to live? What way of life is mandated, given our responsibility for present and future generations? How we are to live is the question of discipleship.

“Faith offers renewable moral-spiritual energy for the journey. I will do what I can, arm in arm with others, to help make the hard transition from industrial civilization to ecological civilization.”

A team effort is essential for humans to find a new way to relate to the earth, said Robyn Hartwig, speaking for the organization EcoFaith Recovery.

A team effort is essential for humans to find a new way to relate to the earth, said Robyn Hartwig, speaking for the organization EcoFaith Recovery.

“We believe God is stirring up in us and others the spiritual and relational power to take public action for the recovery of human life and healing of God’s creation,” said Hartwig, a pastor of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, Beaverton, Ore. “We do not believe we can have one without the other, and we do not believe we can do any of it alone.”

All that EcoFaith does is a team effort, says Robyn Hartwig, pastor of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, Beaverton, Ore., and a leader in the Oregon-based group that cultivates and trains leaders to actively recover and heal creation.

To build that community, EcoFaith Recoverywas founded in 2010 and has brought together a broad network of volunteer leaders and faith-based communities in the Pacific Northwest.

The organization actively cultivates and trains new leaders through its “Practices for Awakening Leadership,” a framework for personal and organizational growth that “supports faith communities in taking courageous public action for the recovery of human life and the healing of God’s creation.”

For EcoFaith that recovery and healing encompasses not just restoring the natural world but also changing ourselves as humans who have grown up in an addictive and dysfunctional system. To change the system, people must change how they relate to it.

“To recover a more regenerative way of being human within God’s earth community is work that we must engage in for the rest of our lives,” Hartwig said.

Making a real difference was on the minds of members of Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church, Dayton, Ohio, as they conducted a strategic plan in 2008. What emerged was the desire to do something to create a better connection to their community, as well as do something positive for the environment.

Making a real difference was on the minds of members of Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church, Dayton, Ohio, as they conducted a strategic plan in 2008. What emerged was the desire to do something to create a better connection to their community, as well as do something positive for the environment.

The following year they created a community garden on the church property that is fulfilling both objectives.

“We now have 60 plots, 15 of them reserved exclusively for growing produce to donate to the local food pantry,” said Ron Root, the project’s lay leader.

Ron Root, a member of Zion Evangelical Lutheran, Dayton, Ohio, is a leader in that congregation’s effort in community gardening and the installation of a windmill to provide the garden with water. (The “Z” was mistakenly carved backward on the cornerstone, and the church has kept it as part of its identity; www.zionelc.org).

The rest of the plots are open to anyone in the community to use for a small fee. The church has created a partnership with Five Rivers MetroParks, a public parks system in the Dayton area, to share resources.

“We now have a closer connection to other people in town and we donate approximately a ton of produce each year to the pantry, so we are supporting the community in multiple ways,” Root said.

The largest obstacle was getting water to the site. “The garden sits 700 yards behind the church, which made running a city-provided water line too cost-prohibitive,” he added. The solution came with a well and a small, farm-style windmill that operates the pump. The water is stored in a raised tank and pulled down by gravity.

The garden also has a large composting area for all to use. The goal of the garden being carbon neutral and self-supporting has been reached.

Among other environmental moves, the church renovated the parking lot, grinding the asphalt for use as a drain pipe slope.

“We see our environmental activities as a major focus, which also supports our ministry of serving others’ needs,” he said.”

“All of my classes, public speaking and published works aim to build moral power and hope for the work of earth-healing and justice-seeking,” said Cynthia Moe-Lobeda, a member of University Lutheran Church in Seattle.

“All of my classes, public speaking and published works aim to build moral power and hope for the work of earth-healing and justice-seeking,” said Cynthia Moe-Lobeda, a member of University Lutheran Church in Seattle.

A professor of theology and environmental studies at Seattle University, Moe-Lobeda has been working for environmental justice for more than two decades and has authored or co-authored four books.

Her most recent, Resisting Structural Evil: Love as Ecological-Economic Vocation (Fortress Press, 2013), “helps people explore how we are intimately connected to sisters and brothers near and far, and how we might transform those connections from being exploitative to being life-giving,” she said.

Moe-Lobeda said ecological and social healing happens on three levels: lifestyle change, which are personal things we can all do; structural change, the ways institutions operate; and consciousness or worldview change, how we view society at large.

Cynthia Moe-Lobeda, pictured with her husband, Ron, is a teacher and writer who views ecological and social healing on three levels. Vocationally, she focuses on a worldview, but she also works for change on institutional and personal levels.

Her teaching, writing and speaking are focused on worldview change. For her, the crisis of climate change is inextricably tied to social justice, what is sometimes called “climate injustice” or “climate colonialism.”

A month in India revealed to Moe-Lobeda that “many economically impoverished people around the world already are displaced and dying due to the climate change … caused disproportionately by the world’s industrialized societies, including ours.”

But she’s keenly aware of the other levels, joining efforts to get Seattle University to divest from fossil fuels and reinvest in clean energy; and making changes at home (bus and bike, rather than a car), motivated by a friend whose family makes one lifestyle change each month.

Though still visited by despair, her faith helps her find hope.

“Once upon a time, I gave up hope,” she said. “I was overcome by the sense that the powers of systemic injustice-racism, imperialism, economic exploitation, ecological devastation and more — were simply too strong.” A Lutheran pastor reminded her of the ramifications of the resurrection.

“This resurrection faith does not excuse us from responsibility,” she said. “It is we humans who must ‘put a spoke in the wheel’ of carbon emissions and the economies that depend upon them. … Nothing we do toward ecological healing is done alone. We work as part of a cloud of witnesses — transcending continents, cultures and time.”