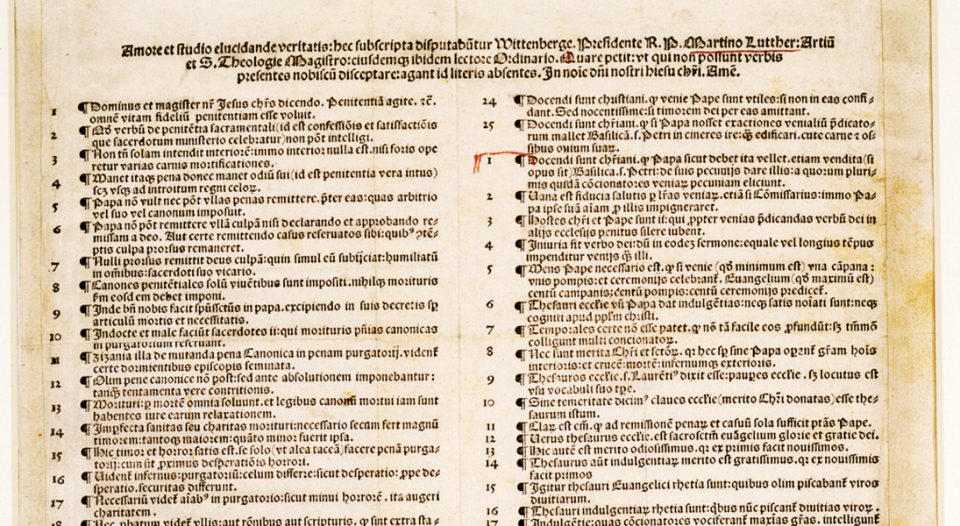

In 2017, Lutherans, other Protestants and even Roman Catholics will mark the 500th anniversary of the German Reformation, when Martin Luther, a relatively unknown theology professor in Wittenberg, penned 95 short statements, or theses, on the practice of indulgence sales for debate at his university.

On Oct. 31, 1517, Luther sent a copy of the theses to Albrecht, the archbishop of Mainz. Ten years later, on Nov. 1, 1527, he remembered the day for “the trampling under foot of indulgences” and promised an old friend that he would toast its memory. People are still remembering 499 years later.

The 95 Theses made two main points. First, they argued from history that the pope, like other pastors, only had authority over ecclesiastical penalties imposed upon flagrant sinners but no authority to reduce God’s punishment or chastisement for sin. Most of the ensuing debate focused on this.

Second, they harshly criticized preachers of indulgences for misleading people into thinking they could ever purchase their way around God’s discipline and penalties for sin by buying the church’s indulgence. This second point directs us to the heart of the Christian message for all people. When gathering on “Reformation Sunday,” we best remember this second point and shape our preaching, teaching and worship accordingly. Three theses summarize this.

Thesis 1: “Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, in saying ‘Do penance …’ (Matthew 4:17) wanted the entire life of the faithful to be one of penitence.”

In the standard Latin Bible of Luther’s day, Matthew 4:17 was sometimes taken as a command to go to the “Sacrament of Penance.” In 1516, however, the first Greek New Testament appeared in print, and Luther learned that the Greek word translated into Latin as “penance” meant “change one’s mind.” Thus, Luther argued that Jesus’ words extended far beyond private confession to a priest, and he insisted that there was no “before and after” in the Christian life.

This thought not only ran against the teaching of Luther’s day, but it also challenges Christian practice today, when many people think they once were sinners but now are at least on the way to becoming saints.

Luther’s first thesis proclaimed that when we stand before God, we are always and only sinners in need of God’s amazing grace. Moreover, when we hear the unconditional promise “You are forgiven,” that word justifies us in God’s sight, clothing us with Christ’s righteousness. Thus, as Luther often repeated, we are at the same time righteous and sinner (simul iustus et peccator) and must daily return to God’s baptismal promises to us.

Theses 92 and 93: “And thus, away with all those prophets who say to Christ’s people, ‘Peace, peace’ (Jeremiah 6:14), and there is no peace. May it go well for all of those prophets who say to Christ’s people, ‘Cross, cross,’ and there is no cross!”

These statements summarize the entire 95 Theses. Luther accuses indulgence preachers of offering false peace to people by proclaiming escape from God’s chastisement by obtaining letters of indulgence. Christians can no more avoid the consequences of sin than they can buy their way out of death.

Many secular and ecclesiastical preachers in our day lure people into the same trap—offering all kinds of “peace” (emotional, financial, familial or societal) and ignoring the truth of the human condition. A letter from 1516 that Luther wrote to a fellow Augustinian, who had just lost his position as prior, clarifies his point:

That person whom no one disturbs does not have peace—on the contrary, this is the peace of the world. Instead, that person whom everyone and everything disturbs has peace and bears all of these things with quiet joy. You are saying with Israel, “Peace, peace, and there is no peace”; instead say with Christ, “Cross, cross, and there is no cross.” For as quickly as the cross ceases to be cross, so quickly you would say joyfully (with the hymn), “Blessed cross, among the trees there is none such [as you].”

It’s tempting to proclaim and believe in worldly peace. The Christian life, however, moves daily from cross to resurrection, from terror to peace, from death to life, and—as in our daily baptism—from drowning to rising. This movement properly distinguishes law (which shows sin and puts to death) from gospel (which proclaims forgiveness and brings to life).

It also demonstrates what Luther called the theology of the cross, that is, the revelation of God in the last place we would reasonably look (namely in the midst of sin, suffering and death).

Thus, our proclamation on Reformation Sunday, and every Sunday in between, is simply: “You have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians 3:3). In later writings, Luther associates this “saint and sinner,” “dying and rising” and “hidden life of faith” with baptism. Perhaps the best way to commemorate the Reformation may be simply to return to our baptisms, where we were marked with the cross of Christ forever.

Citations from Martin Luther’s 95 Theses with Introduction, Commentary and Study Guide by Timothy J. Wengert (Fortress Press, 2015).