Last December a commercial from Poland touched hearts around the globe. In it, an older Polish man spends weeks practicing English everywhere he goes, to the amusement of his neighbors and consternation of his dog. At the end of the commercial, the man’s motivation is revealed: he boards a plane to England, where he is warmly welcomed into a house and says to the small girl inside, “Hi. I’m your grandpa.”

The ad had a message that resonated with many—love’s ability to speak in the first language of the heart.

My preaching professor in seminary, Craig Satterlee, now bishop of the North/West Lower Michigan Synod, taught us that when sharing a message, “it’s not about getting the gospel said; it’s about getting the gospel heard.”

Focusing on getting the gospel heard, he said, helps us look beyond ourselves and consider: “Who are you preaching to? What is the good news for them? How do they need to hear it?”

Gary Chapman, a pastor and author of the best-selling book The Five Love Languages might argue that love works the same way as preaching: it’s about “getting the gospel heard,” offering love in the first language of the heart.

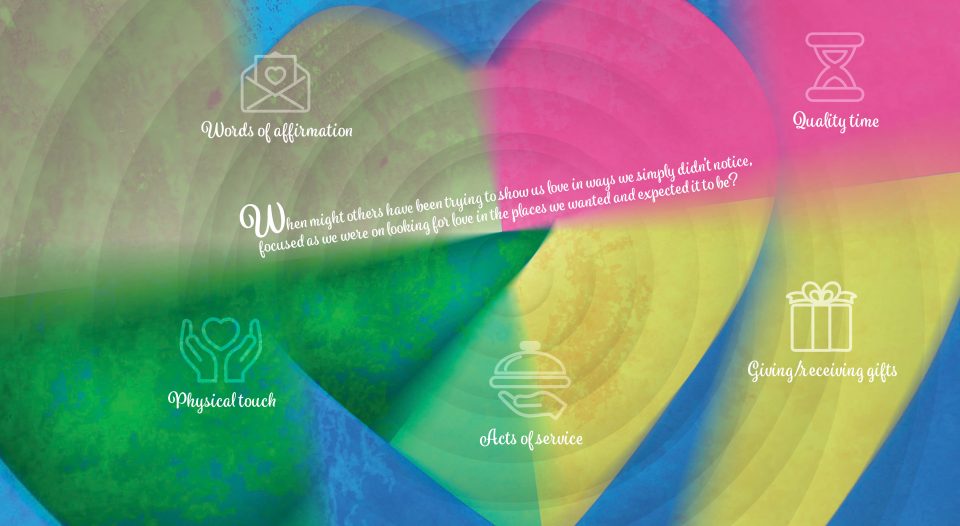

Chapman proposes that there are five primary ways human beings experience love:

- Words of affirmation.

- Quality time.

- Giving/receiving gifts.

- Acts of service.

- Physical touch.

All of these love languages can speak to us in some ways. But usually one or two are our primary languages, the ways we feel most loved and those we miss the most when we don’t receive them.

Most people, Chapman writes, naturally show love in the ways they want to be loved, the “language” they best recognize. This approach seems sensible, recalling Jesus’ advice to “do to others as you would have them do to you” (Matthew 7:12).

In his work with couples, however, Chapman found that this Golden Rule doesn’t work when the people we love need to “hear” love in a different way. The solution? Chapman advocates for learning the love languages of others, as well as our own, and striving to show love accordingly. It’s what has been called the “Platinum Rule”: do to others as they would have you do to them.

I thrive on words of affirmation. My 4-year-old daughter treasures every gift she has ever received, a bird feather from the park no less than a fancy necklace. My 8-year-old son craves physical touch, and he and my husband bond over wrestling or tickle fights. Our 18-month-old toddler absorbs all the love he receives, and we watch to see how his personality and love languages will emerge.

I know the love languages of my family because I know them; or at least, I’m getting to know them more and more each day.

As I reflect on other relationships in my life and ministry, I thankfully recall the joyful moments when I have been able to love others as they needed to be loved. And I remember well, with pangs of regret, the times when I have failed—not for lack of love, but because I didn’t consider how others needed to receive love from me.

Perhaps the key to loving our neighbors as ourselves is not to love them in the same way, lest we project our wishes and identities onto others. Perhaps Jesus means that we love our neighbors by seeking to know them, to consider them in their uniqueness as fully as we consider ourselves. Perhaps to be truly loved—by God and by others—is to be known.

Martin Luther, following Jesus’ command to love the neighbor, found a holy calling in all human relationships—with family, friends, neighbors, even enemies. How might learning Chapman’s five love languages help us, as Lutherans, to love others and to receive love in return?

For me, this begins with grace: the promise that when we fail to love others as we should, we are not hopelessly unloving (or unlovable).

Sometimes it’s simply a miscommunication of love languages: sin causing us to trip over our assumptions and expectations in the love we give and the love we receive. That insight also nudges us to extend grace to others in our lives from whom we sought love and felt disappointment.

When might others have been trying to show us love in ways we simply didn’t notice, focused as we were on looking for love in the places we wanted and expected it to be?

The gospel says God loves humankind in all our complexity. Fully known and fully loved, we are free to love boldly: seeking to know and to love our neighbor as she is. And even when we fail, the love of God in Christ will find us in the language of our hearts.

To learn more about “The Five Love Languages,” visit 5lovelanguages.com.