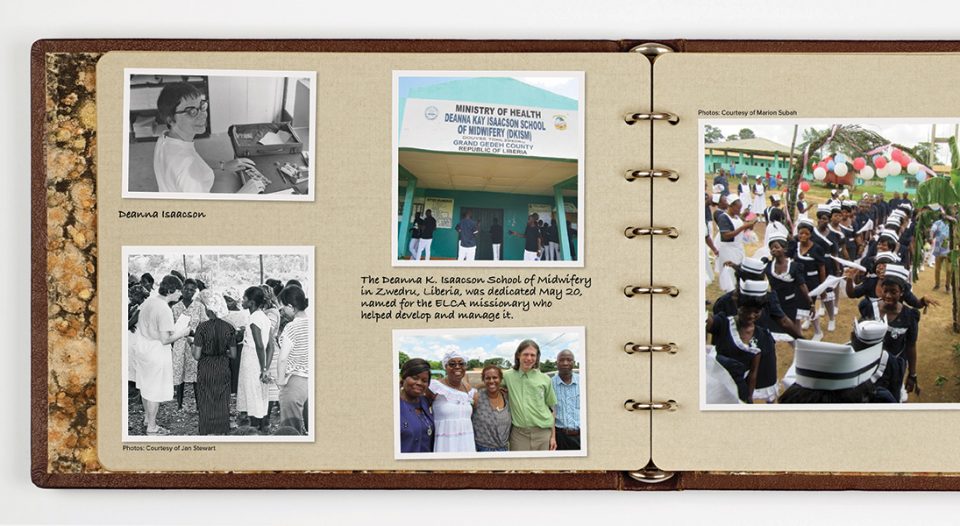

When 43 midwives graduated from a three-year midwifery training program in Liberia on May 20, a 44th person was honored: the late Deanna Isaacson, an ELCA missionary from 1966 to 2000.

The school, operated by the Liberian Ministry of Health, was renamed the Deanna K. Isaacson School of Midwifery to honor the woman who helped develop and manage it beginning in 1983.

The Isaacson School is in Zwedru, Grand Gedeh County, and serves six counties in southeastern Liberia, a rural region where access to health care can be problematic.

For Liberian women, the presence of a certified midwife can make the difference between life and death. Midwives handle all aspects of a delivery except caesarian sections, and they can safely treat hemorrhage, sepsis and other situations that might otherwise trigger maternal death.

In a country with one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world, “we are vulnerable because we don’t have enough doctors and less than half the number of midwives that we need,” said Marion Subah of the Human Resources for Health project of the Maternal and Child Survival Program in Liberia.

Graduates of the Isaacson School will help close that gap.

Lifelong commitment to Liberia

As a new graduate of nursing and midwifery, Isaacson was “surprised to learn upon arrival that I was expected to teach in a midwifery and practical nursing program at Curran Lutheran Hospital in Zorzor,” she recalled in a letter to congregations in 1999.

She quickly developed a reputation for being a meticulous teacher, said Jeannette Kpissay, a former missionary colleague who met Isaacson in nursing school. “I remember one day helping a student at Zorzor get the right amount of medication in a syringe. When she got frustrated she said, ‘You’re as bad as Miss Isaacson. She makes us do it exactly right!’ ”

Besides teaching and training midwives at hospitals of the Lutheran Church in Liberia, Isaacson designed curricula and organized hospital staffing and procedures. In the 1980s, as a staff member of the Christian Health Association of Liberia (CHAL), she was recruited to help launch the new Midwifery Training Program–South Eastern Region in Zwedru.

“Very few students from that region came to Curran or Phebe Hospital, and when they did, they didn’t go back,” Kpissay said. “The idea behind opening the school in Zwedru was that people stay in the region where they are trained.”

“[Deanna] wasn’t the director, but she was the one running the school,” said Subah of her close friend and longtime co-worker. “She developed materials, organized teaching, and worked with CHAL, UNICEF and other groups to get it off the ground.”

Opened in 1983, the school graduated a steady stream of capable, certified midwives until Liberia’s long civil war forced it to close.

“Because the president was from Grand Gedeh County, the rebels completely destroyed Zwedru,” Subah said. “When Deanna and I came back for the first time in 1992, we couldn’t see anything. After the rains started, the grass and trees had swallowed everything up. You couldn’t see a house, a town, anything.”

Early in the war, Isaacson stayed put and continued working to assure the continuity of health services provided by CHAL members like the Lutheran Church in Liberia. “Our desks faced each other, and when war came, we joined them into one,” Subah said. “All the others had left.”

Later Isaacson was evacuated, but she returned to participate in a Catholic Relief Services assessment team designing a food distribution system for people affected by the first wave of the war.

Throughout the war, Isaacson continued her work for CHAL, sometimes from the Ivory Coast. Kpissay said Isaacson’s rule for staying in the country was: “When does my presence endanger other people? When people around me feel they have to protect or hide me, I’m out of here.”

Continuing her legacy

The Isaacson School reopened in 2008, thanks to partnerships between the Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare and international donors. It began graduating students again in 2011.

During the graduation and dedication ceremony, traditional dancers and fanfare greeted graduates, their families and dignitaries. Isaacson’s nephew Lee spoke about his aunt’s life, and Sumoward Harris, retired bishop of the Lutheran Church in Liberia, led the prayer of dedication.

“Deanna wasn’t into drawing attention to herself, and she would have had a lot of suggestions about other people that it could have been named for,” Kpissay said. “But she would have been very humbled by this gesture.”