On Jan. 21, 2017, Rafael Malpica Padilla, executive director of ELCA Global Mission, donned his clerical collar and set out to join the Women’s March in downtown Chicago. On the way he encountered some women holding protest signs—including one that read: “Keep your rosaries out of my ovaries.”

“I asked the women if they were going to the march,” Malpica Padilla recalled, “and reluctantly they engaged me.” Eyeing his collar skeptically, they answered: Yes, they were marching. When he told them he was marching too, they replied with surprise and curiosity: “What kind of priest are you?”

The question “What kind of priest are you?” is about theological identity; it applies not only to priests, but to the priesthood of all believers—the church.

What kind of people of faith are we? For Lutherans, shaped by Martin Luther’s insight that all of life is part of our calling from God, the question of theological identity is not only about the interior faith of our hearts and minds, nor is it only a description of how we live within church walls. It’s also about the life of faith we live out in the world. This has always been the essence of Lutheran Christianity, Malpica Padilla argued, pointing to the “simple question” Luther posed in a 1519 sermon: “How do we stand before God, and how do we stand before neighbor?”

“At the heart of our Lutheran identity is a relationship with God—justification by faith,” Malpica Padilla said. Justification is a free gift of God’s grace apart from human works. But if justification is nothing less than the total restoration of our personal relationship with God, it is also something more: a transformation of our relationships with others.

For Lutherans, justification is “not only freedom from” sin and brokenness, it is “also freedom for” a purpose, he added.

Where Luther wrote that sin is being curved in on the self, “justification means striving toward the other,” Malpica Padilla said. “It is lifting your chin up so you can see the other—and not just the other who looks like you, but especially the other who is different from you.”

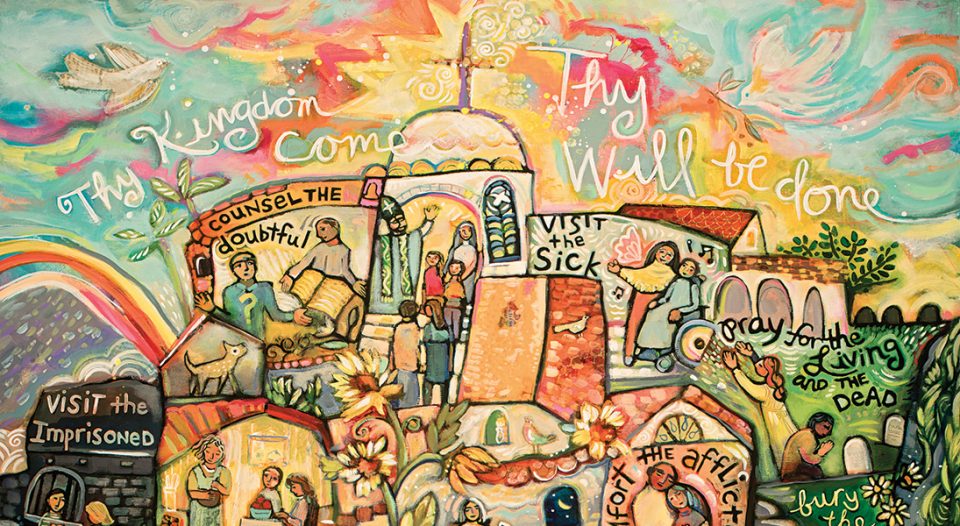

Love of God and neighbor, for Luther and for Lutherans today, is a theological identity that guides our whole lives. As Lutherans in the ELCA and around the world reflect on the past 500 years, it’s worth considering how the Reformation roots of social action continue to guide Lutheran identity and calling—exploring how we stand not only before God, but also before our neighbors. What kind of Christians are we today? And what kind of church will we become?

As Lutherans in the ELCA and around the world reflect on the past 500 years, it’s worth considering how the Reformation roots of social action continue to guide Lutheran identity and calling.

Reformation roots:

A holy calling and a Common Chest

In the 2016 collection The Forgotten Luther: Reclaiming the Social-Economic Dimension of the Reformation, Cynthia Moe-Lobeda wrote that Luther never wavered from his belief that “works do not cause salvation.” Still, “Luther also insisted that works are a vital part of life for people who are justified by Christ,” particularly “works that embody ‘love to our neighbor,’ ” she said.

Moe-Lobeda found that “for Luther, that norm of neighbor-love pertains to every aspect of life for the Christian.”

Ryan Cumming, program director for hunger education with ELCA World Hunger, notes that Luther’s opposition to indulgences stemmed in part from the fact that their sale created “opulence built on the backs of people who could barely afford to feed themselves.” This led Luther to write in his 95 theses that giving to the poor was “a better work” than purchasing indulgences, and that to buy an indulgence rather than help a neighbor in need was to purchase “the indignation of God.”

In the Large Catechism, Luther argued that the commandment against murder applies both to the taking of life and the failure to preserve it: “If you see anyone who is suffering from hunger and do not feed her, you have let her starve.”

Reflecting on the commandment against stealing, Luther also boldly critiqued the “free public market” of his day: “The poor are defrauded every day, and new burdens and higher prices are imposed.” Luther urged Christians instead “to promote and further our neighbors’ interests, and when they suffer any want, we are to help, share, and lend to both friends and foes.”

As a way for the government to respond to the needs of the vulnerable, Luther and others in Wittenberg established a “Common Chest” in 1522. The chest offered financial support for orphans and poor children, dowry support for poor women, interest-free loans, refinancing for high-interest loans, education or vocational training for poor children, and vocational retraining for adults. Health care was added later, as the Common Chest funded the services of a town physician and paid the cost of hospital care and other treatments.

The Wittenberg Common Chest order spread to other cities and towns and became a model for how church and state could work together for the sake of all neighbors.

Hand in hand:

ELCA action, accompaniment and advocacy

The Reformation legacy of social action, rooted in a theological identity of freedom in Christ to serve the neighbor, can also be glimpsed in the history of Lutherans in North America, who built not only churches but also schools, hospitals and other social agencies.

The ELCA’s first social statement was “The Church in Society: a Lutheran Perspective,” adopted in 1991. It reads in part: “In faithfulness to its calling, this church is committed to defend human dignity, to stand with poor and powerless people, to advocate justice, to work for peace, and to care for the earth in the processes and structures of contemporary society.”

“This is Lutheran theology,” Malpica Padilla said. “We are free to see and engage the other, and mission cannot happen unless we see the face of God in the other.”

This theological orientation provides the foundation for accompaniment and advocacy, two related approaches to ELCA social action. “The other is not the object of my action. It is not ministry to, but ministry with and among the neighbor,” he said. “When we engage in social activity, it’s not ‘for them,’ but because, in working together, we are dismantling systems that prevent humanity from living in the full abundance promised by Jesus: life in relationship with God and with one another.”

Malpica Padilla knows that many Christians, especially in a divided and partisan culture, are reluctant to think of faith as “political.” This, he urged, should not prevent us from recognizing that “it is the work of Christians to advocate for the poor and marginalized.”

Citing Luke’s Gospel, which consistently frames Jesus’ mission as a reversal of an unjust social order, he added, “I cannot allow political ideology to claim for itself what belongs to the gospel. I am a committed follower of Jesus Christ; I do [what I do] because of the gospel.”

“This is Lutheran theology. We are free to see and engage the other, and mission cannot happen unless we see the face of God in the other.” — Rafael Malpica Padilla, executive director of ELCA Global Mission

Faith in action:

World Hunger

Cumming describes his work with ELCA World Hunger as grounded in the love of neighbor. “Hunger is a system of broken relationships,” he said. “We know there is enough to feed people, but some are excluded and don’t have access to create and purchase food.” When we “seek out the image of God in our neighbors [and] see one another as revelations of God among us,” he said, we realize that “need doesn’t just exist ‘over there,’ in that other person, but in relationships with others.”

World Hunger funds an average of 250 grants each year to 60 countries through companion synods and partners. International grants support projects like eco-friendly farming, responses to malaria and HIV and AIDS, support for those affected by domestic violence or incarceration, and advocacy for human rights, including gender equity.

Cumming also views this work as rooted in a Lutheran understanding of vocation. “God has graced each person with gifts to share in the community, but if we can’t [due to need], the community suffers, and we suffer.”

Like Luther’s Common Chest, World Hunger supports partners in “helping people find ways to use their own talents and skills to provide for themselves and participate in the community,” Cumming said.

Faith in action:

Global Church Sponsorship

Despite growing up as the son of two pastors and attending an ELCA college, Andrew Steele, director for ELCA Global Church Sponsorship, didn’t feel a strong connection to church as a young adult—until he spent a year in South Africa through the ELCA’s Young Adults in Global Mission (YAGM) program. “There, church was an integral part of life. … I learned so much about spirituality and public church,” he said.

Global Church Sponsorship supports long-term missionaries; the YAGM program; ministry projects by global partners, such as new church buildings and training workshops; and an international women leaders’ initiative that provides scholarships to women for ELCA seminaries and undergraduate programs.

The ELCA’s accompaniment model for global mission took getting used to, Steele admitted: “At first, you want to build and do things; then your job is to sit there and watch the water boil, and you think, ‘What am I doing here?’ ”

Steele’s epiphany came after he joined local farmers in planting a field of corn. After a long day’s labor, Steele was proud of his efforts—until he learned that guinea fowl had eaten all the corn and the planting would have to be done again. Sharing the experience with his South African neighbors, Steele realized he “wasn’t there to plant the corn. We were there to be humans together … to live in community.”

Faith in action:

Domestic Mission

When Stephen Bouman, director of ELCA Domestic Mission, considers a Lutheran approach to social action, he looks to “the powerful public nature of the sacraments.”

“Luther always called us to the world,” he said. “When we baptize a child, it’s baptismal ministry to follow her into the world … we struggle for the world of that child.” Likewise, sharing communion also means considering those who need to eat, “extending the eucharist into the world,” he added.

Since 2009, Domestic Mission has been committed to making sure that at least 50 percent of new-start congregations serve immigrants, places of deep poverty or communities of color. In 2016 that number hit 57 percent. “We are slowly becoming a church that is changing [to reflect] what America is becoming,” Bouman said.

This strategy, far from a church dictated by culture, represents for Bouman a reclaiming of the roots of the Reformation—and Christianity itself.

2017:

The church at a crossroads

Five hundred years after the Reformation, the ELCA faces “a Lutheran crossroads” that will determine the future of the church, Malpica Padilla said. But for many Christians in a North American context, he said, Jesus is regarded less as the source of our love for neighbor and more as a “personal spiritual trainer—that’s how we have reduced Jesus, so that the trainer works on us one hour a week.”

The disconnect between self and neighbor, church and world, faith and action, means “we have domesticated Luther, [making him] hostage to cultural and institutional life,” he warned. “[Yet] our Lutheran identity pushes us into the world.”

If Lutherans reclaim the love of neighbor that was so central to the teachings of Jesus and Luther, Malpica Padilla believes “the core identity of our theology” will show our neighbors, including the “spiritual but not religious,” that “Lutheran identity means something.”

On his way to the march that January day, when he was asked “What kind of priest are you?” Malpica Padilla responded by telling the women that he was a Lutheran pastor. As he shared with them the theological identity that prompted him to march, the women inquired: “Where is your church? We’d like to go.”

Faith in action, Malpica Padilla concluded, is not only identity and calling—it is also evangelism.