Lectionary blog for Jan. 7

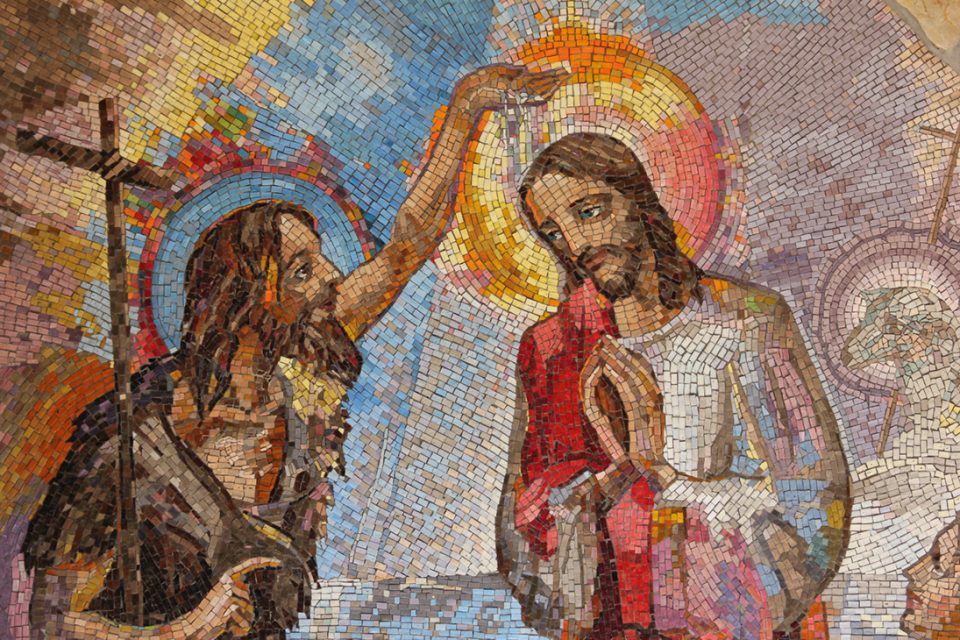

The Baptism of Our Lord

Genesis 1:1-5; Psalm 29;

Acts 19:1-7; Mark 1:4-11

On the liturgical calendar, yesterday was the Epiphany of Our Lord, when we celebrate the revealing of Jesus as the Son of God, the Messiah, the Light of the world. It’s a time when we start to connect the dots between the first chapter of Genesis—In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep. … Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light—and the first chapter of John’s Gospel—In the beginning was the Word. … What has come into being in him was life and the life was the light of all people. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

The images of light and darkness carry with them many interpretations; one of the most pervasive and persistent is sin and forgiveness, evil and redemption.

John the baptizer appeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism for the forgiveness of sins (Mark 1:4).

I’ve been haunted for many years by the vague memory of an old TV show. I remember the word “sin-eater,” and a teenage boy dressed in rags going into a torch-lit room and taking a piece of bread off a man’s chest. He gobbled it down while sobbing and screaming in apparent torment. That’s all I could recall. Sometimes the internet is an amazing research tool. I typed in “sin-eater” and in a matter of minutes all was revealed. The show was a 1972 episode of Night Gallery based on an old tradition in parts of rural Wales and England in which one of the villagers was the sin-eater. When someone died, food was placed on their chest, which the sin-eater ate while reciting a prayer. The deceased’s sins then passed from his or her soul into that of the sin-eater.

In the TV show, the sin-eater had died, and his wife persuaded their son to eat the bread laid on his father’s corpse—he took on not only his father’s sins, but those of all who had died in the village for many, many years. No wonder he sobbed and screamed. The episode was called “The Sins of the Fathers,” echoing the biblical admonition that “the sins of the parents shall be visited upon the children …” (Deuteronomy 5:9, among other places).

Proclaiming a baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

The question of what to do about our guilt, shame and remorse for having done wrong has haunted humanity for a very long time. Everything from human sacrifice to appease the anger of the gods to little children crying, “I’m sorry,” while promising to be good fits within this equation. Sometimes we try to put the blame on the powers that be for being arbitrary and too strict; other times we take on the very concept of sin and shame itself, proclaiming it outmoded and unhealthy. Or, if we keep the idea of sin and shame, we redefine them in such a way that the things we do are acceptable and understandable, while the evil done by others is totally reprehensible and worthy of punishment. And so it goes—under whatever labels and ethical codes we devise, we continue to struggle with what to do when that still, small voice reminds us that we have failed to behave.

Proclaiming a baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

Today we celebrate the Baptism of Our Lord. Those of us in the Lutheran church are most familiar with the baptism of infants. Because of this, we sometimes have a hard time understanding the “baptism for the forgiveness of sins” aspect of this day. For us, baptism is mostly about the celebration of an innocent child’s inclusion in God’s community of love, and the community’s commitment to share with the parents in the raising of their child. The forgiveness of sins is something of an afterthought—after all, how does sin apply to a little baby? There is some thought that the idea of “original sin” arose as a response to this question.

But notice—those coming to be baptized by John in the Jordan were adults, not children. And the language about “repentance” and “forgiveness of sin” wasn’t exclusive to mean old John the Baptist—throughout the gospels, Jesus called people to repentance and talked about sin and forgiveness frequently. Any of us who have lived to any level of maturity and honest self-reflection have struggled with the reality of our moral and ethical failures. What are we to do about our awareness of (and feelings of guilt and remorse for) our very real shortcomings, our not-very-original sins?

Hiring a sin-eater is not only out of the question, it is also totally unnecessary—not because we have no sins, but because God in Christ has already taken them up. Martin Luther put it this way: “That is the mystery which is rich in divine grace to sinners: wherein by a wonderful exchange our sins are no longer ours but Christ’s and the righteousness of Christ not Christ’s but ours. He has emptied Himself of His righteousness that He might clothe us with it, and fill us with it. And He has taken our evils upon Himself that He might deliver us from them … in the same manner as He grieved and suffered in our sins, and was confounded, in the same manner we rejoice and glory in His righteousness (D. Martin Luthers Werke; Weimar, 1883).

And though we may not be able to remember our baptism, we can remember the baptisms of others. And week after week, as we come into the church, there is the font—we can see and touch the water. After we pray the confession, we hear the words reminding us that God does, indeed, forgive us. Following the sermon, we say the creed, reminding ourselves that we believe in “the forgiveness of sins.” Later, the pastor stands at the altar, lifts the bread and cup, saying those beautiful words: Shed for you and for all people for the forgiveness of sins. Then we make our way forward to the altar where we eat and drink, not our sins but our salvation. Finally, we are sent forth to shine the bright light of God’s love and grace and forgiveness into a dark and lonely world.

Amen and amen.