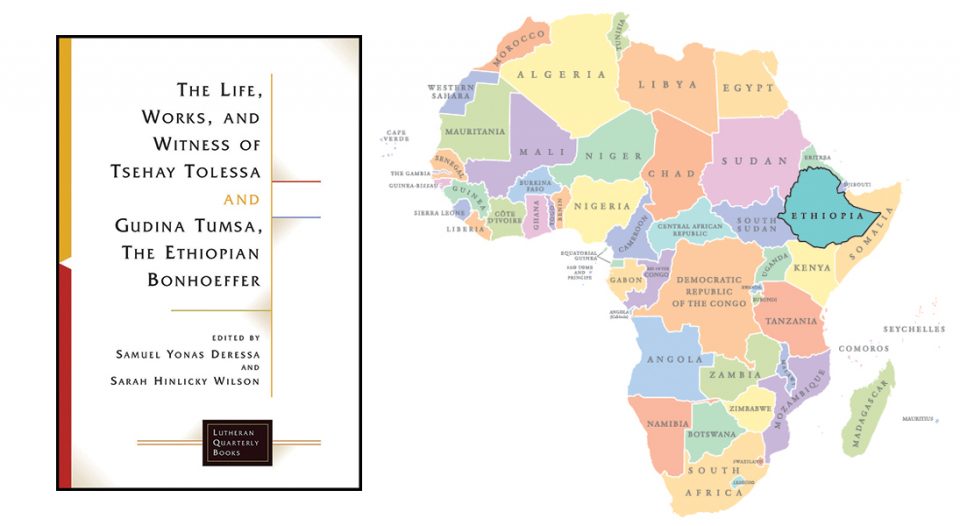

Sarah Hinlicky Wilson is an ELCA pastor in the Slovak Zion Synod, the editor of the theological quarterly Lutheran Forum, and a visiting professor with the Institute for Ecumenical Research in Strasbourg, France. With Samuel Yonas Deressa, she co-edited The Life, Works, and Witness of Tsehay Tolessa and Gudina Tumsa, the Ethiopian Bonhoeffer (Fortress, 2017), a collection of writings by and about the martyred Lutheran couple.

Living Lutheran spoke with Wilson about these two figures who may not be familiar to many Western Lutherans, but who played an important role in global Lutheran history.

Living Lutheran: What drove you to put together this new collection on Gudina Tumsa and Tsehay Tolessa?

Wilson: Years ago, my co-editor Samuel Yonas Deressa told me about Gudina and got me a copy of the first Ethiopian edition of Gudina’s writings. I was completely fascinated. Then Samuel mentioned that he knew of a book written by Tsehay in German. I got hold of the book and discovered that it was actually a translation from Norwegian of a book based on conversations with Tsehay in Amharic, which was a second language for both the author and Tsehay, an Oromo speaker. I added to this game of linguistic telephone by translating the German into English because I was so moved by Tsehay’s story.

I sent my translation to Lensa Gudina, one of the daughters of Gudina and Tsehay, who had never read it. Lensa was able to work through it with Tsehay shortly before Tsehay died and correct a few small mistakes, thus making our English edition the “authorized” version of the story. At that point, both Samuel and I felt that we had the core of a great book on Gudina and Tsehay for a North American audience.

There’s a growing interest in global Lutheran theology. … Here we have primary writings by one of our most important African theologians and the firsthand account of their lives by his extraordinary wife. In fact, it’s incredibly rare to come across a married couple who are equally remarkable Christian witnesses and so articulate about their faith. Gudina and Tsehay are the Martin [Luther] and Katharina [von Bora] of the 20th century.

How would you describe the couple?

Gudina and Tsehay were among the most remarkable Lutherans who ever lived—despite the fact that so few Lutherans have even heard of them. We are hoping to change that with our book.

Both of them came to Christianity as young people through encounters with Lutheran missions. Gudina was ordained a pastor, and Tsehay joined him on some of his preaching tours, a powerful evangelist in her own right. Gudina … won a scholarship to study at Luther Seminary (St. Paul, Minn.) in the 1960s. When he returned [to Ethiopia], he was appointed general secretary—for all intents and purposes, the bishop—of his church, the Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus.

Not long after taking office, the [Ethiopian] emperor, Haile Selassie, was deposed and replaced with the Communist Derg regime. … [Gudina] went from criticizing the imperial regime to criticizing the communist regime, and ultimately paid for it with his life. He may have been the lucky one, though: Tsehay was imprisoned without accusation, trial or sentence. She was tortured and then left, forgotten, in prison for 10 years before her release. Both Gudina and Tsehay were persecuted for their refusal to [kneel] before worldly powers.

What impact did Gudina and Tsehay have on Lutheranism today?

In North America we still have the idea that Lutheranism is a northern European phenomenon that followed immigrants to the U.S. Certainly that’s where Lutheranism originated and has deep roots, but if you want to see where it’s growing by leaps and bounds, you have to look to East Africa. … If we look just at the example of Ethiopia, it’s clear that Gudina is the Lutherans’ inspiration, role model and ideal. He managed to hold together what so often gets put asunder: proclamation of the gospel of faith in Jesus Christ with service to the neighbor; personal piety with social activism; charismatic worship with political protest.

He challenged Western missionaries who wanted to fund either evangelistic activities or diaconal works, but not both. Gudina insisted: We are whole people, and so our Christian ministry must be holistic. No more choosing between body and soul, individual and community. And no more telling us the best way to go about our work. Trust us Ethiopians to be Christians as fully as you are.

Why is Gudina called the “Ethiopian Bonhoeffer”?

Gudina was being called the “Ethiopian Bonhoeffer” quite soon after his death. Like [Dietrich] Bonhoeffer, Gudina was a Lutheran pastor, deeply rooted in the Lutheran theological tradition, an impassioned preacher and deep thinker. Like Bonhoeffer, Gudina was forced to reckon with an abusive and idolatrous government demanding abject loyalty of its citizens. Like Bonhoeffer, Gudina was executed not simply because he was a Christian, but because he was a Christian who challenged the state’s absolutism. His confession of a Lord greater than the state was intolerable to the pretensions of the state.

Like Bonhoeffer, Gudina was executed not simply because he was a Christian, but because he was a Christian who challenged the state’s absolutism.

Ultimately, Gudina was kidnapped off the street and murdered by government officials. What makes his story even more painful, however, is that the government refused to acknowledge what it had done. For the rest of the Derg’s rule, they denied all knowledge of his whereabouts. Tsehay and their children tried desperately to get news. It was only after the regime change, and a very extensive search on the part of Gudina’s brother, that they were able to locate his body in a grave outside the old imperial palace, and give Gudina a Christian burial.

He should certainly be recognized as a martyr by the church. But I’d add that we should also recognize Tsehay as a confessor for her steadfast fidelity to the gospel during the truly appalling conditions of her decade of imprisonment. In fact, after her release, she started a new congregation.

The Ethiopian church has a long history of playing a vital role in the global church as it has developed, including as forerunner to the Reformation. What do you attribute that vitality to?

Ethiopia may be the best example of taking Luther’s priesthood of all believers seriously. Evangelism is not primarily the task of the ordained clergy—it’s everybody’s job, and they actually do it.

What do you feel all Lutherans stand to gain by learning from the life and witness of Gudina and Tsehay?

I’m continually impressed by Gudina’s insistence on wholistic ministry. In North America we tend to see a bifurcation in churches—[usually] they are either really bold in proclaiming Jesus but quiet in the face of social and political issues, or they are really outspoken on social and political issues but seem to choke on the name of Jesus. There is no either/or in Gudina’s ministry and theology. … We don’t need to be in a situation of [his] political extremity to benefit from this witness—though probably all Christians at all times need to be prepared for that possibility.