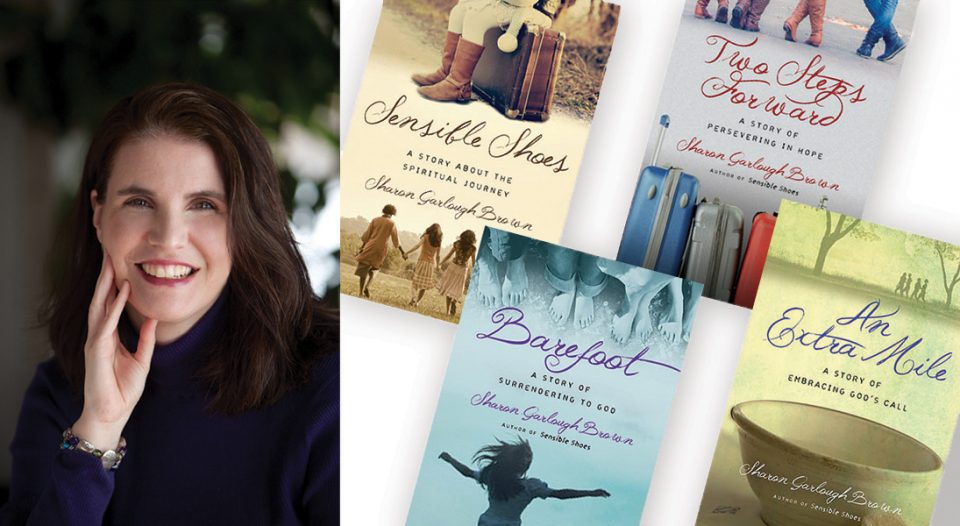

Several years ago, I picked up Sharon Garlough Brown’s Sensible Shoes (IVP, 2013). The back cover promised that it would blend ancient spiritual practices with contemporary life using fiction. I was intrigued. Since then, I’ve walked with Brown’s characters through the “Sensible Shoes” series, finding that their stories and movement toward God has informed and stimulated my own. The fourth and final book, An Extra Mile, is out this month, just in time for Lent.

I spoke with Brown about the power of fiction, the importance of spiritual formation and where Lutherans might find themselves in her work.

Living Lutheran: Could you describe the “Sensible Shoes” books?

Brown: [It] begins with Sensible Shoes, which is the teaching book [in the series]. You have four characters who meet at a retreat center to learn different ways of prayer, different ways of being present with God, and to grow in the grace of knowing themselves and [in] the grace of community. As the characters are growing in their relationships and [in their] friendship with God, the readers are invited to take that retreat journey with them. Embedded within the fictional story are [study guides] that explain the spiritual disciplines. A reader has [the] opportunity to read this book just as a story or to take the journey of retreat with the characters.

The subsequent books are all about how the things that they have learned are being integrated into their lives with God. They aren’t tidy books. … The characters are no longer on retreat, and the question really is: How will they continue to grow and pursue God when they no longer have the structure of meeting together regularly? … Life is difficult in the subsequent books; there are challenges within their families, there are challenges of illness, there are challenges of loss. … My hope and my prayer for the readers is that they will find ways to draw closer to God, in deeper communion and intimacy, as they get to know themselves more deeply, so that the characters really become mirrors for readers to see themselves.

Why is it helpful to approach formation from the standpoint of fiction?

I think we will pick up a nonfiction book expecting that we are going to learn something, and with fiction it facilitates, I hope, an encounter with God—a stirring of imagination. Certainly, Jesus is a master at storytelling and understands the power of story as he tells parables that invite us to consider what the kingdom of God is like.

I hope that with this combination of spiritual formation and fiction, readers are catching a vision. Not in a didactic sort of way, but [that] simply by watching how the characters are wrestling and struggling and growing and responding to God and one another, it becomes an invitational perspective to a reader.

I hope that with this combination of spiritual formation and fiction, readers are catching a vision.

Why do you feel that your work will resonate particularly for Lutheran readers?

I long for readers to taste and see that God is good. I long for readers to discover the love of God—the height, the length, the depth and the breadth of God. I long for readers to be set free from captivity of guilt and shame and regret. The grace of God, the good news of the gospel, sits at the heart of these books. Those are just some of my longings: that readers will leave with a sense of hope, a sense of faith, a sense of courage; that as the characters, in their messy and imperfect and stumbling lives, are encountering the grace of God, I hope readers also are encountering God’s goodness and grace.

What do you see as the benefits of spiritual formation to the church today?

Maybe I should define spiritual formation: this is the grace of God at work in our lives to make us more like Christ, to conform us to the image of Christ. How are we being formed as the people of God? It’s very personal, but it’s also a corporate process in terms of how we are growing in Christlikeness. I think we are good at doing things perhaps for God; I don’t know that we are as practiced at being with God, and what it means to cultivate a life of prayer, and to understand the movements of our own hearts and our own sin patterns, and the ways that we resist the grace of God in our lives and the ways that we move toward God. So I think it’s an essential, foundational piece that then undergirds our mission and our ministry, that our deeper communion with God, our deeper conformity to Christ’s likeness, our deeper friendship with the Lord, that all of this becomes the foundation for our interaction with the world as ambassadors for Christ.

What are some of the real-world responses you’ve seen to your stories and characters?

I think the most common thing I hear from people is that they saw themselves in the characters—maybe bits of themselves in each of the characters; often one or two of the characters really resonate. It can be a reaction of “Wow, I really understand her struggle and I see my own struggle in her life.” It can also be very oppositional: “I don’t like what I see in that character and I feel like the mirror has gone up to my own life and struggles and sin.”

The other thing I most commonly hear is a longing for community: “Oh, I wish I had a group like that,” or “I wish I had a spiritual director who could walk with me and help me to notice and name the work of the Spirit in my life,” and “Where do I go for community?” That’s one of the reasons I’ve been so passionate about providing resources for the book. The Sensible Shoes Study Guide [is] a 12-week primer in spiritual formation. It’s designed for both individual and group experience. When I wrote Sensible Shoes I had two primary longings: one, that readers would encounter God as they read in significant ways; and two, that they would find ways to connect with one another, because God designed us for community—for authentic, life-giving, vulnerable, transformational community.