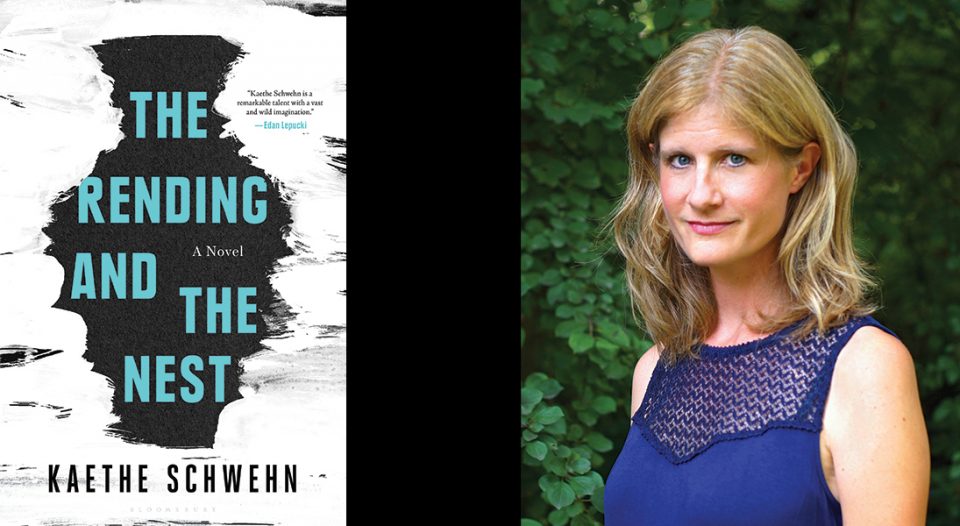

Kaethe Schwehn has been writing about faith throughout her career. Her first book, Tailings (Cascade, 2014), is a memoir of personal and spiritual grappling set against the backdrop of Holden Village, a Lutheran retreat center in Washington’s North Cascades. Her new book, The Rending and the Nest (Bloomsbury USA, 2018), takes a decidedly different approach to the topic. The dystopian novel explores belief and doubt, motherhood and loss, community and relationship through the lens of fiction.

Living Lutheran spoke with Schwehn, who teaches writing at St. Olaf College, Northfield, Minn., about balancing darkness and light in her novel.

Living Lutheran: Could you describe The Rending and the Nest?

Schwehn: My book is a post-apocalyptic novel, set in Minnesota, that opens about three years after the apocalyptic event (referred to as “the Rending”) takes place. When the book opens, the protagonist, Mira, finds out that her best friend, Lana, is pregnant. About 100 pages into the book, Lana gives birth to an inanimate object instead of a baby, and things progress from there.

How did this story and these themes capture you?

For me, when I’m writing, there’s what I’m letting myself know consciously, and then, when I get done writing, what I realize has been going on subconsciously. After I got done writing [this book] I realized I was writing very soon after the birth of my daughter, and as I wrote, my son was born. So I was very much experiencing both motherhood for myself, and witnessing my friends go through the experience of motherhood, and seeing how drastically different that was for women.

What happens in my book is influenced by hearing stories of loss and miscarriages. I saw how hard it was for [friends] not just to have this horrible thing happen but to live in a culture where we don’t have good rituals really for that kind of loss.

Even though women in the novel are giving birth to inanimate objects and that is so strange and weird, the emotional grounding of the story was in this sense of these women then not knowing how to relate to these objects—and feeling a deep connection, and also feeling like by remaining too connected to them, they were going to destroy themselves with grief. Mira starts to create these nests in which they place the objects—that starts to give them a sense of relief a little bit.

I’m not saying it’s the same thing by any means, but one of my hopes about this book is that even though it is full of absurd and bizarre and strange things, it is very grounded in real human grief and loss and the reality of relationships: friendship, romance and how we deal with our parents’ history, [and how we] resist that or grow into it.

It’s clear that your Lutheran faith is important in your work. Would you talk about that?

[Tailings] is a memoir about a year I spent living at Holden Village. That memoir is set when I’m 22 and coming to terms with a failed relationship and my parents’ divorce and not knowing what I want to do with the rest of my life. It deals a lot with issues of community and faith, and many of those things carry over into the novel.

The protagonist of the novel (Rending) is right around the same age I was in the memoir. She’s wrestling with questions of faith. Her father was a pastor, and when the apocalyptic event occurred, she was 17 and feeling like she just didn’t buy into the Christian faith anymore. Then the apocalyptic event occurs, and it seems very easy to excise that part of herself from who she becomes after the event. She just doesn’t tell people that her father was a pastor or that religion was part of her life.

What was interesting for me was to watch and see as these strange events occur [how] she wrestles with how much and what parts of her faith creep back into her life. She starts building these nests, she starts developing ritual as a way to cope with mystery and grief and suffering. She becomes a leader for her community and starts to help them learn to tell a story about themselves. Seeing what aspects of faith pull through and resurface in spite of her resistance and her desire to squelch that part of herself was really interesting.

What led you to this genre, and how are you hoping readers will engage with this book?

What’s important to know about the book is that it doesn’t ultimately end in darkness. It’s about a probing of that darkness, for sure, but, you know, “the light shines in the darkness and the darkness did not overcome it” (John 1:5). I think that image is at the center of my faith, and I hope at the center of the book, as well—though the light that continues to shine is a complicated light.

But it’s important for people to know that going in because there are some post-apocalyptic and dystopian books that are completely brutal in terms of their visioning of the world. … I was eager to write a novel that reflected a little bit more hope and humor, that thought about [the question of] if the worst happened to us, how would we pick ourselves up and move on? I think that we would do that with community and relationship and ritual and humor and some joy, too.

What do you see as the heart of the novel?

It’s partly, how do we make sense of that which is inexplicable? Part of it is, how do we learn to tell stories about ourselves that bring life instead of death? Part of it is, who gets to tell the stories of our lives? There’s so much right now in the news—who gets to tell stories and which stories do we believe and how lives and laws can be manipulated by who is telling the story, and what parts of the story they decide to include.

What would you like to say particularly to Lutheran readers, as they pick up your book for the first time?

A writer’s greatest hope is that a reader will find themselves somewhere on the page, or find a question that they’ve been carrying with them articulated, or that they’ll be annoyed or frustrated, and that that will start a conversation. When I was at Holden, there was a woman named Gertrude. During the passing of the peace she would say, “May the spirit of God disturb you.” I feel that way about good writing too—that the hope is not always “I hope you love this,” but that it disturbs you somehow.