For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate (Romans 7:15).

A searching and honest friend of mine once said, “You Christians always want to talk about sin. What does it really matter that a man supposedly died for my sins? Did that appease your God in heaven—somebody taking the rap for the world’s screwups? Why is the whole notion of sin so important, especially if God seems to forgive everything anyway?”

You’ve probably noticed that the Apostles’ Creed jumps immediately from Jesus’ birth to his suffering under Pontius Pilate. The drafters of the creed want us to quickly notice something about Jesus—a Lord born to die. And he dies “as a sacrifice for sin and a model of the godly life,” as one of our offertory prayers puts it.

Lutheran theologian Ted Peters’ words are helpful here: “We sugarcoat our garbage. Everyone has a stake in hiding the truth of sin. This makes uncovering the mystery of how sin works difficult, because wherever we dig, lies rush in to fill the hole. Perhaps the only way to get at the truth of sin is through confession.”

One of the reasons we’re so enamored with news in all its variety is that headlines subconsciously remind us that even though we may have our little flaws, at least we’re not as messed up as that guy on Channel 4.

Millard Fuller, founder of Habitat for Humanity, once spoke in a seminary setting with an audience of 200 pastors. He asked, “Is it possible to build a house so large that the house is sinful in the eyes of God? Raise your hand if you think so.” Every pastor raised a hand.

He next asked: “Then at what precise square footage does the house become sinful?”

Several moments of silence filled the room. Finally, one pastor quietly said, “When it’s bigger than mine.”

This may be when sin has us most in its power—when we see it in others rather than ourselves. Celebrating the great gift of freedom this month, we realize (in our most honest moments) that we aren’t really all that free after all. We are “captive to sin,” as our confession puts it. For many, it isn’t a happy truth to admit we’re captives in the land of the free.

We are “captive to sin,” as our confession puts it. For many, it isn’t a happy truth to admit we’re captives in the land of the free.

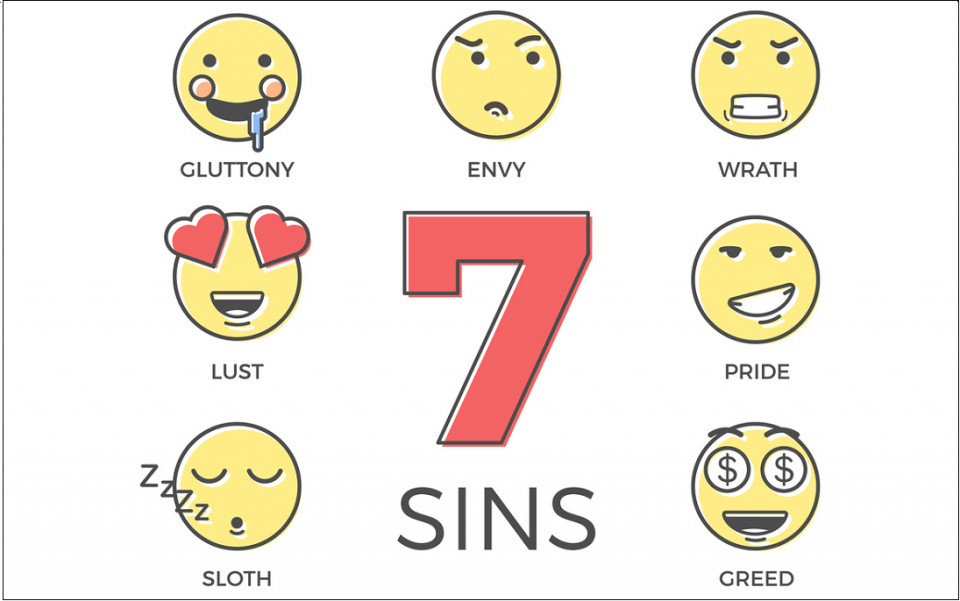

I’ve found it important in my spiritual life to name specific sins out loud before Christ. The ancient breviary of slipups known as the “Seven Deadly Sins” (lust, envy, greed, anger, gluttony, pride and sloth) has been spiritually helpful. Gregory the Great (540-604) called the list “a classification of the normal perils of the soul in the ordinary conditions of life.”

There’s a hopelessly prideful character named Count Olaf in the “Lemony Snicket” children’s stories. “You know,” says the snide Count to the homeless Baudelaire siblings, “there’s a big world out there, filled with desperate orphans who would gladly swim across an ocean of thumbtacks just to be eclipsed by the long shadow that is cast by my accomplishments.”

Self-righteousness, the creeping notion that we may not need God after all, is perhaps the largest temptation for most Christians who’ve never been thrown in jail.

•••

Freedom. Thank God we’re free. And not so free, right?

“Wretched man that I am. Who will rescue me from this body of death?” asked the apostle Paul (Romans 7:24).

Who indeed?

How would you answer the questions posed by my friend? Perhaps the best response is to think of the cross. An innocent man hanging there says, “Father, forgive them; for they don’t know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34).

Luther encouraged making “the sign of the cross” daily to remind a Christian of the shape of baptism. The sacrificial life of Jesus is the antidote for sin.

As we get used to the idea that we are sinners in need of forgiveness and grace, we hopefully become more grace-filled ourselves. Filled with a power that liberates.