As churches across America face declining attendance and questions about their sustainability, ministry leaders have sought new ways to connect with their communities—particularly in rural areas where congregations are often aging and geographically dispersed.

The Northwest Synod of Wisconsin took a step last year to help make those connections. The synod applied for and received a state grant to provide training materials and education for congregations, communities, families and individuals struggling with addiction.

The partnership began with Aimee Wollman Nesseth, an ELCA chaplain who serves as program coordinator for the Northwest Wisconsin Healthcare Emergency Readiness Coalition. She knew grants were available for addiction education in affected communities of northwest Wisconsin. The area, long a national hotbed for alcoholism, has been plagued by rural meth labs and hit hard by the burgeoning opioid epidemic.

Seeing a unique opportunity for the church and the government to work together and reach vulnerable people, Nesseth contacted the Northwest Synod of Wisconsin. Greg Kaufmann, an assistant to the synod bishop, was excited to hear from Nesseth. For years he had watched the addiction problem worsen in the synod’s territory.

“I’ve lived in rural northwestern Wisconsin for 38 years,” he said. “I never thought our problem would be this bad. I was sure it was a big-city problem. We’ve long been the No. 1 alcohol-consuming state in the country, but I had no idea that we would become the epicenter for both meth and the opioid crisis.

“The meth crisis has not gone away at all, and the opioids are so much easier to get ahold of. They’re now the drug of choice for a whole bunch of people.”

Kaufmann is no stranger to the ravages of addiction. His brother has been in recovery from alcohol addiction for more than 10 years and an acquaintance recently attended a treatment center where all except one person were dealing with opioid addiction.

He also serves as volunteer director of Select Learning, a separately incorporated ELCA ministry that provides continuing education resources for clergy and laity. While doing research, Kauffman came across Kal Rissman. An ELCA pastor and a native of rural southeast Minnesota, Rissman has spent 40 years working in chaplaincy and ministry to people coping with addiction, first at a hospital in North Dakota and then in Indiana, where he serves a congregation today.

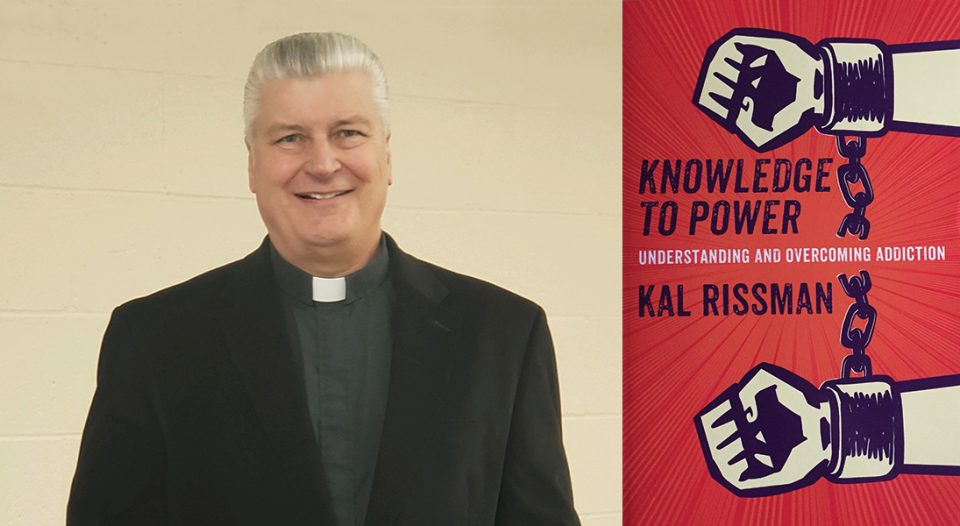

Rissman has written a book, Knowledge to Power: Understanding and Overcoming Addiction (Outskirts Press, 2018) and created DVD resources to help educate clergy, church leaders and community members about addiction and how churches and family members can help but not enable people.

Kaufmann said Rissman’s 40 years in addiction ministry are rare: “Most people don’t last 10 years. People get burned out.”

Rissman is known for a way of speaking that feels familiar to people in rural ELCA congregations whom the synod is trying to reach. He had spent his whole life in the rural Midwest, and when Rissman talked about addiction, Kaufmann said, “he turned our language into regular-people talk. … It’s him telling stories and suggesting ways to both understand and deal with it.”

Using the grant money, the synod purchased resources from Rissman and Select Learning that are geared toward families, friends and fellow church members of people in active addiction. “That’s mostly who churches will come into contact with—the families,” Rissman said.

Congregations and their leaders should be careful of two tendencies, he added. The first is a “judgmental and moralistic view of people who are addicted,” he said. “Churches need to talk about addictions the same way they talk about any other disease.”

The second: Congregations and their leaders need to be careful not to feed co-dependent or enabling behavior. Rissman said some volunteers may be overly active at church to avoid dealing with addicted family members at home.

“Church members and pastors are very forgiving too quickly,” he said. “They offer absolution without repentance.” Congregations should be careful not to shame families or addicts, he cautioned, but should also avoid enabling active addiction by providing money or excuses.

He also said people in recovery are often open to beginning a spiritual journey, even if they first refer to “a higher power” rather than God. “You have to start where people can start in their spiritual life,” he added. The church, he explained, can offer a respite to people in addiction by opening their eyes to a grace-filled, loving God who is not “standing around with a big stick to whack you.”

Rissman told a story of a man named Kenny (last name withheld) whom he met in his addiction work in a hospital in Jamestown, N.D. A farmer who milked 120 cows every day, Kenny had been dealing with alcohol addiction for at least 30 years when Rissman met him.

Ultimately, Kenny got into Alcoholics Anonymous, found a sponsor and became sober. He asked Rissman, who was part-time pastor of a local congregation, if his coming into the church might cause the roof to cave in.

“He started coming to services, then regularly, and by the time I left the congregation, he was president of the council,” Rissman said. “He was still pretty rough around the edges, but his faith was genuine. People could see it.”

Stories like this give Rissman and others hope that education and training in addiction ministry can lead to more recovery and healing for communities across America, beginning in programs like the one at the Northwest Synod of Wisconsin.

With the state grant, the synod brought Rissman to Wisconsin in February to lead forums for clergy and lay leaders. His work incorporates healing from grief and loss, both of which often go hand in hand with addiction.

Kaufmann said grants like the one the synod received are also available in other states. He suggested that interested pastors and congregational leaders contact the Lutheran office of public policy for their state or directly contact the state agency that deals with this issue. “They’re eager to find partners,” he said.