“When you stop trying to force the Bible to be something it’s not—static, perspicacious, certain, absolute—then you’re free to revel in what it is: living, breathing, confounding, surprising and, yes, even magic” (Rachel Held Evans, Inspired).

I lost a good friend in May. We had spent many hours together over the years, discussing and debating. She had told me about her childhood, her marriage, her babies, her transition from her conservative evangelical background to the Episcopal Church. Her sudden death at age 37 affected me deeply, and I mourned the loss of her wisdom. Though I never met author Rachel Held Evans and our conversations took place only in my imagination, our relationship was real to me and her influence profound.

As a Catholic child in the 1960s, I didn’t read the Bible. In those days we weren’t encouraged to do so on our own, without the guidance of the priests. The only Scripture in our house, my parents’ wedding Bible, sat untouched on a shelf.

When I joined the ELCA in my 30s, I felt like a complete biblical novice. Oh, sure, I heard the readings in church on Sunday mornings, but frankly many of them washed over me, especially the often-disturbing Old Testament passages. After becoming a Sunday school teacher and later joining the church staff as spiritual formation director, I studied the Bible as if cramming for a big exam. And while eventually I became conversant, if not fluent, I remained intimidated and put off by much of what I read. I learned how much Martin Luther loved the Bible—he described Scripture as the cradle that holds baby Jesus. I wanted to love it too, but couldn’t quite get there.

Like all great stories, the Old Testament contains contradictions and conflicts and reconciliation and joy. To approach it as a rigid series of answer books, Evans wrote, is to miss the entire point.

Then I discovered Evans. Here was a young, gifted Christian writer from a totally different church background who clearly knew her Bible. But instead of tiptoeing around or explaining away the questions, contradictions and messiness that I found so daunting, she plunged right in and grappled with it all—and encouraged her audience to do the same.

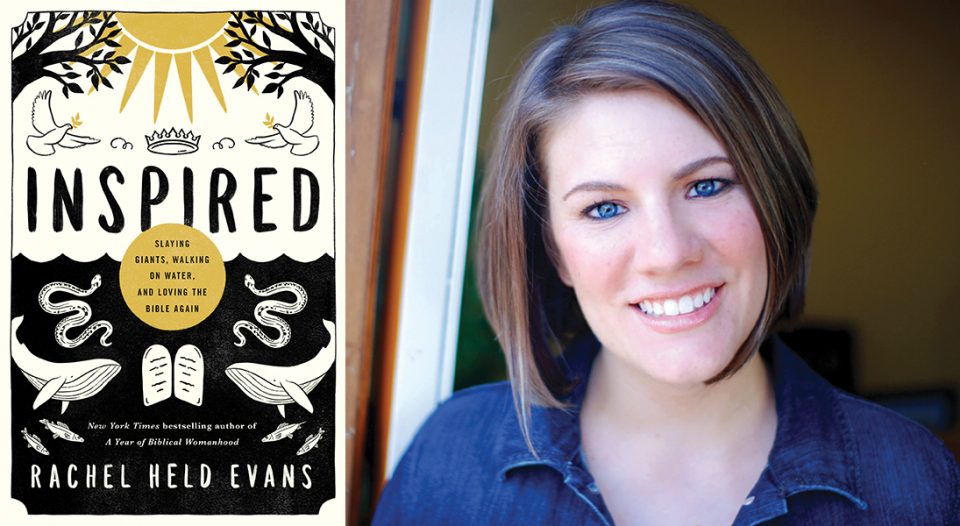

My favorite book of hers, Inspired, gave me a new set of eyes for my encounters with Scripture. While I was most comfortable with Evans’ thoughts on the Gospels, it was when she led me out of my comfort zone, to the bloody battlefields and strange characters of the Old Testament, that I learned the most. She helped me see it as an epic story told by an ancient, oppressed people in a tumultuous but loving relationship with their creator. Like all great stories, the Old Testament contains contradictions and conflicts and reconciliation and joy. To approach it as a rigid series of answer books, Evans wrote, is to miss the entire point. Our doubts and fears and even our anger can and should be brought to our engagement with the Bible. God deserves nothing less than our all. Like Jacob in his wrestling match, we may end up shaken and bruised but also blessed.

Nowadays, I lead our weekly adult Bible study. Thanks to Evans, I no longer feel ill-equipped when we tackle a difficult passage. Together, our small group debates and discusses. And if we come to no agreement at all, that is fine. We are taking a complicated but exhilarating journey—just like life itself. And as our group talks, I often feel the presence of this special person, still challenging and delighting me.

May all who miss her, including the many she never met, be comforted by the God whom Rachel loved, and in whom I believe my dear friend rests.