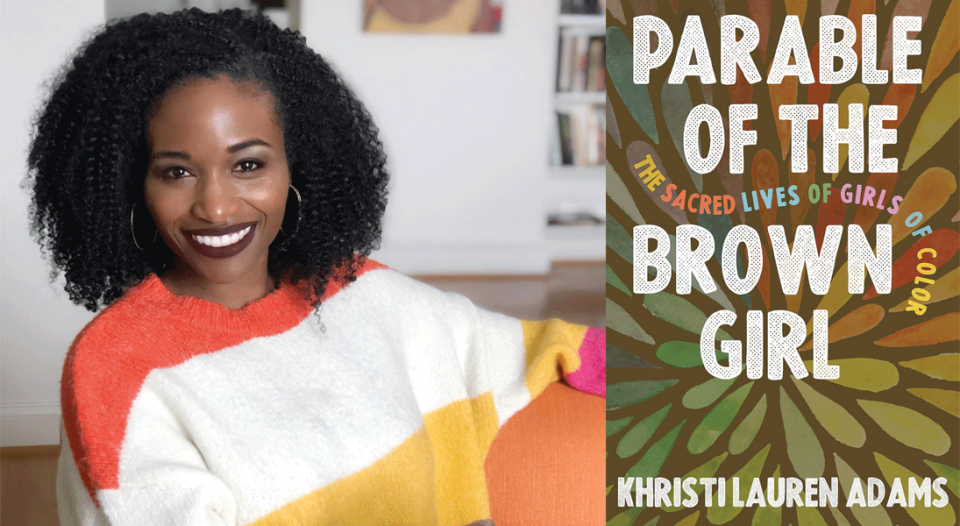

Khristi Lauren Adams is a speaker, a pastor of the American Baptist Churches USA and an advocate for young women. She’s also the founder and director of the Becoming Conference for teenage girls. Her new book, Parable of the Brown Girl: The Sacred Lives of Girls of Color (Fortress Press), juxtaposes her experiences as a black woman with those of several young women of color she has developed relationships with through her ministry.

Living Lutheran spoke with Adams about her book and what she hopes it will mean to her readers.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about your book?

Adams: Parable of the Brown Girl shares seven different narratives of profound personal encounters with young black girls and how specific cultural and spiritual truths emerged through the girls’ wisdom alongside their stories. The book aims to help the reader understand the plight of black girls in contemporary society and the cultural [and] historical overlap between other generations of black women, and offers a theological perspective with respect to the issues mentioned.

It is about how the unlikeliest of narratives can teach us the most important lessons in life, and it sheds light on how black girls have been deprived of positive cultural and theological narratives about themselves.

What was it like placing your personal stories alongside those of the young girls you feature in the book?

It wasn’t difficult at all because, [with] the majority of the moments that I have had in my relationship with the girls, I have seen glimpses of myself or recalled my own similar experiences alongside theirs. In many ways, their stories are my stories and reflect my own, and I was amazed by how consistent many of their struggles are with the stories I have heard from other black girls and women intergenerationally. I recognize their struggles and experiences in my own life.

When I walked through the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and read about the lives of other black women and girls dating back to the 1500s, the cultural similarities were astonishing. Young black women in contemporary society are confronted with similar issues as many of those who have come before them. Their stories share profound spiritual wisdom, yes, but they also highlight challenging cultural truths about the ways black women are viewed and treated that are far too long overdue for serious, revolutionary change.

These girls do not share center stage in our public or churchly discourse. Many of their stories go unheard and, therefore, we do not get the opportunity to glean their wisdom.

What do you think might surprise your readers—and how are you hoping that will bring about deeper empathy and awareness of the complexity of these lives?

I think each reader, depending on their background and perspective, will take away something different from the book. For some of us, it will be confirmation of things we already knew, and for others it will bring up things they were completely unaware of. These girls do not share center stage in our public or churchly discourse. Many of their stories go unheard and, therefore, we do not get the opportunity to glean their wisdom. My intention is to put them in the forefront through this book and to center them and their experiences in ways that we haven’t seen or accepted as a society.

I want to tell their stories and I want as many people as are willing to listen to experience what I have through them. Although the girls are black, the experiences are provocative and relative to a diverse community of readers. Everyone—no matter your ethnicity, race, faith tradition or background— can learn something from their stories and their questions and conclusions.

How are you hoping to invite your audience into the conversation your book creates, as well as the action it spurs?

My audience is primarily adults who want to gain more understanding of the experiences of black girls—how they can create relationships with and become better advocates for those girls. This also includes those who already have personal or professional connections to black girls—parents [and] family, educators, counselors, clergy, laypeople, et cetera.

I hope the Lutheran audience and readers in general will read this book and discover a more positive and more wholesome way of understanding the uniqueness of black girls’ lives and experiences. I hope that Christian readers will seek out intentional ways of working with and on behalf of black girls in their churches and communities.

My intent is to encourage others to read the girls’ stories and to encounter the Spirit of God within them in the same way that Jesus, through his parables, encouraged others to reflect on theological truths through the lives of the overlooked. These girls’ stories are important to God. These girls are important to God. That’s the overall sentiment I am trying to express in my writing.