In the early 1980s, beginning at Mount Katahdin, I backpacked the length of the Appalachian Trail (2,100 miles) south from Maine to Georgia. Sometimes I’d go three days without seeing another hiker.

One night I stayed alone in a trailside shelter near Pearisburg, Va., a common occurrence back then. Two weeks later, northbound hikers—a young couple who were social workers—were murdered in that same shelter. They had shared a meal with a man who soon after ended their lives—a troubled man who had been abused as a child. Crime is exceedingly rare on the trail. Even so, this spooked me a bit.

Twenty years passed. A friend directed me to an article describing a strange incident within a mile of that same stretch of the Appalachian Trail.

Two fishermen shared a meal with a man who then attacked and severely injured them. They escaped and got help. The assailant was the same man who had committed the murder of that young couple. A model prisoner for two decades, he had been paroled to live with his mother in Pearisburg.

***

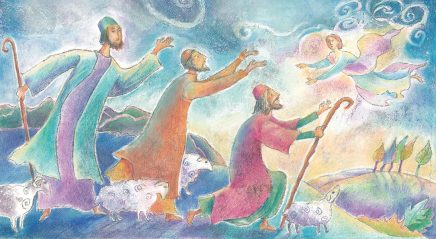

The story of the weeds and wheat (Matthew 13:24-30) is among the oddest Jesus ever told. At night, “an enemy” sows initially undetectable weeds, set to wreak havoc weeks later. Once the weeds emerge, the workers are shocked and outraged, ready to call out the Agronomy National Guard. The head farmer is aware of the potential damage, but he chooses a strange course of action: “Let both of them grow together until the harvest” (13:30).

I once watched one of those epic 18th-century Scottish movies, Rob Roy. The good guys were easily distinguished from the bad. As the movie progressed, I noticed my palpable loathing for this wormy little man who so reeked of affluence, arrogance and disdain for the poor that I found myself almost cheering in the end when the villainous twerp finally got it in the gut.

God may say, “Vengeance is mine” (Romans 12:19), but there is something inside us all that sometimes prefers to say vengeance is ours.

“What this country needs,” I often hear, “is a return to the Bible.” And I couldn’t agree more. In our nation’s capital last June, a Bible was famously hoisted high for the country to see. What may genuinely surprise us is the Jesus we find within its pages.

We find a man who proclaims that ultimate judgment on human life is God’s decision alone. God, who allows time for repentance and change in even the worst of us. Who hangs on the cross and forgives the very people executing him.

There is very little “action” from Jesus on the cross, truly little rear-end kicking. Like the advice in the parable, Jesus appears to be doing not much of anything except hanging there, among the weeds.

“For in gathering the weeds,” we are told, “you would uproot the wheat along with them.” Swiftly enforced righteousness, often accompanied by anger and hatred, can result in the losing of a collective soul.

My daughter, a public defender, once asked me to visit a man (whom I’ll call Josh) on death row. Josh, with a history of mental illness, killed a woman one night while he was off his medication. There was a huge public cry for Josh’s execution. His sentence was eventually changed to life in prison.

Today, Josh leads a daily Bible study and serves as a mentor for new inmates who are entering the system. We write each other monthly. He is an excellent example of someone who has been given time to repent for a past crime.

***

Jesus compares the kingdom of heaven to “someone” (Matthew 13:24) who sowed good seed in his field.

Not just anyone would offer the subsequent parabolic advice.

Not just anyone would spend his life hanging around folk everybody else had given up on.

And not just anyone would die convinced that the way of the cross could save a fallen world.

Be careful with the Bible when you open it.