Lectionary blog for Oct 18, 2020

Isaiah 45:1-7; Psalm 96:1-9;

1 Thessalonians 1:1-10; Matthew 22:15-22

Why do we ask questions? Sometimes we simply want to know the answer. Other times we’re trying to impress someone, either by asking a good question or by stumping the responder. At other times we are trying to create intimacy. My wife’s love language, for example, is quality time with lots of questions about what she is thinking and feeling. Yet, at times we use questions to disrupt intimacy, either through queries that make people uncomfortable or are meant to discredit the responder. Questions are powerful because they make a request or demand of someone else that a statement does not.

The Gospel readings for this week and next feature questions that follow a specific rabbinic pattern. Now, anyone who has been invited to a Jewish Passover seder (or participated in problematic “Christian seders”) will remember a part of the evening in which children were meant to ask four questions about what made Passover different from all other nights. This tradition comes from the earliest written rabbinic document, the Mishnah (Pesachim 10:4).

Another document preserves a first-century rabbinic tradition of a group posing four types of questions to a rabbi named Joshua/Jesus (BT Niddah 69b). These questions were meant to sort out tricky issues and, simultaneously, to test Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah. They followed a pattern:

- A question about wisdom to discern the proper response to an issue of purity.

- A vulgar question about a woman with multiple husbands.

- A question of prioritization of laws.

- A question meant to elicit truth through stories.

The Gospel of Matthew knows about these questioning traditions in first-century Judaism and purposely frames Jesus’ conversations in Jerusalem along those lines. Remember, the chief priests, the Sadducees and some Pharisees had already decided that Jesus was a threat to law and order and were trying to get rid of him (21:45-46). The only thing that kept them from abducting Jesus was the fear of popular protests against violence by authorities. To sway the crowds against Jesus, the authorities attempted to use questions to undermine him with challenges to his supposed teaching authority.

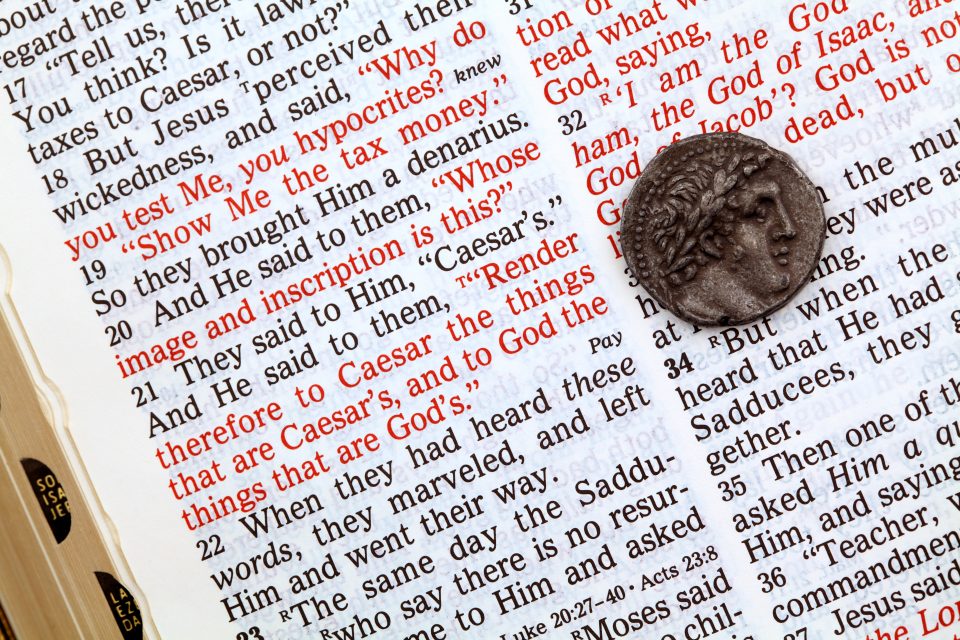

Jesus threaded the needle of their question by pointing out that since Caesar’s image was on the coin, they should give it back to Caesar. Yet, even more important is to give to God what is God’s.

The questions in Matthew follow the pattern above. In attempting to discredit Jesus, some Pharisees plotted to entrap him with an impossible question about ritual purity (22:15). They were so eager to trap Jesus, that they collaborated with their enemies, the Herodians, who happily accepted Roman support and money. The group asked Jesus if it was right to pay taxes to Caesar. On the one hand, paying taxes to Romans acknowledged Caesar’s right to be lord over Jews. The tax also was used to fund construction of temples for idol worship and wars against those who resisted the empire. Many considered the Roman coins to be impure. On the other hand, advocating for not paying taxes to the Romans would be a mark of revolt. Either answer involved tangling Jesus up with an idolatrous, violent, unclean empire that he largely sought to avoid.

Jesus threaded the needle of their question by pointing out that since Caesar’s image was on the coin, they should give it back to Caesar (with a none-too-subtle rebuke to participation in the Roman economy). Yet, even more important is to give to God what is God’s. The Roman coin carried Caesar’s image, but humans carry God’s image (Genesis 1:27). Jesus used the question about paying taxes to a Roman lord to reaffirm the necessity of using our bodies for the Lord.

After the first group of Pharisees failed, some Sadducees decided to challenge Jesus. Again, their question conforms to the pattern: they asked a vulgar question about a woman with multiple husbands, in this case to ridicule Jesus’ Pharisaic belief in life after death and the resurrection of the dead. The Sadducees invoked the law of Yibbum (Deuteronomy 25:5-10) in which the wife of a man who had died without children was to marry her brother-in-law to raise up sons to preserve the name of her dead husband. After such a family all died, who would be married to whom in the resurrection?

Jesus responded to their question by saying that humans will apparently be asexual in the resurrection (Matthew 22:30). Then he went further to say that the Sadducees, who only regarded the Bible’s first five books as authentic Scripture, had failed to understand their abbreviated canon. When God introduces Godself to Moses as the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, God is not some god of the dead but of the living. Therefore, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were to be regarded as alive in God, even though they had died.

The human response to Jesus’ answers to both of these questions was astonishment (22:22, 33). People had sought to use questions to undermine Jesus when violence wasn’t practical, but it backfired. As we seek to follow and emulate Jesus, his responses to these questions should make us sensitive to the ways that some authorities use rhetoric and violence hand-in-hand in our day to discredit those who work toward the kingdom of heaven. Jesus used his answers to those who sought to harm him to remind his hearers that all humans are image-bearers of their Creator, who loves us and saves us from death.

Next week we turn to two sincere questions, and what they tell us of the messiah we follow.