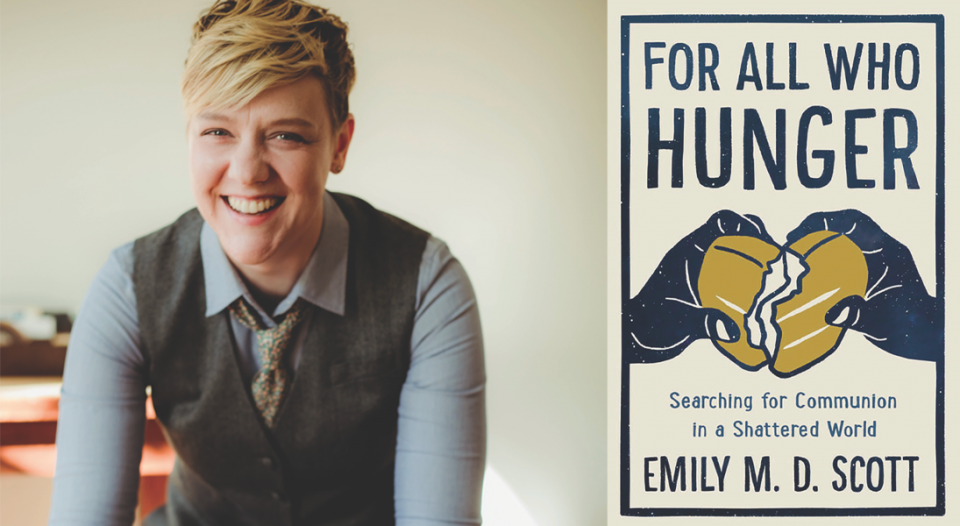

When Emily Scott started dreaming up St. Lydia, an ELCA congregation in Brooklyn, N.Y., that worships around a dinner table, she didn’t know that she would help spark a dinner church movement that would spread across the country. Her new memoir, For All Who Hunger: Searching for Communion in a Shattered World (Convergent, 2020), focuses on the humble beginnings of this ministry as she explores her journey planting a new form of church among the buzz and commotion of New York City.

Living Lutheran spoke with Scott about how her book covers loneliness as a young pastor, learning how to engage with the past and present of her congregation’s neighborhood and how she led her quirky, budding community through it all.

Living Lutheran: For All Who Hunger is about providing a unique faith space in a busy, often anonymous, city for people who are lonely. But it’s also an exploration of your own need for community and love. Could you talk about that?

Scott: I feel really glad to have had the chance to share some of what it’s like to be a younger, single pastor. I think sometimes younger clergy are asked to carry a lot of weight in the church—they’re supposed to be rescuing the church, but also everyone’s kind of annoyed at them because they’re millennials and they want to do things differently—so there’s a lot of conflicting messages coming at younger clergy.

For a lot of younger and single clergy folks, there’s a tremendous amount of sacrifice that takes place to serve the church that doesn’t always get named. And there’s a real sense of becoming quite isolated from your peers as a clergyperson. It puts a bit of a wall between you and other people around you, and there’s a sense of isolation. So I think it’s helpful to start a conversation about that reality, because it helps people feel less alone in that, and it helps the church understand the particular nuances of a younger clergy’s experience, which is really important. Because it is an experience that a lot of folks, especially younger women, share and also feel they can’t talk about.

As you write about the process of dreaming up St. Lydia, you ask, “Is it possible to create a church that’s made of real life?” What have you learned is necessary to do so?

What comes to mind for me is a comment that one of my congregants made, and she had grown up in a quite evangelical context. She felt that there was this divide between who she was Monday through Saturday and the person she was supposed to be on Sunday when she came to church. And it almost felt like, when she came to church, she was being asked to hide pieces of herself that were too raucous, and she said, “I’ve been so happy at St. Lydia’s to find a place where who I am on Saturday night can be the same as who I am on Sunday at church.”

There’s nothing about the louder, brasher, “funner” parts of ourselves that God doesn’t embrace or connect to, and I’m really interested in creating spaces where there’s a sense that all the sides of yourself are equally embraced and visible.

What do you think it is about a dinner church format that creates those spaces?

A piece of it was an environment that was participative. It was all set up in a way that allowed us to learn from each other. And I tried to really embrace ambiguity—different people would share their stories as part of the sermon, and I tried to never wrap that moment up in a neat bow and say, “This is the moral! This is what we learned.” I really let the edges be a little raggedy, because that’s life, that’s our theology—the sense that we don’t always have it figured out and we don’t always have to resolve every dissonance.

And also being around the table, cooking, sharing, there was a lot of laughter, there was a lot of connection, there was a lot of humanness that was taking place in church. And we were marking all of that as sacred with our liturgy. I think there was a blessing of ordinary, real life—humanness that allowed people to feel at ease with their full sense of self.

There’s nothing about the louder, brasher, “funner” parts of ourselves that God doesn’t embrace or connect to, and I’m really interested in creating spaces where there’s a sense that all the sides of yourself are equally embraced and visible.

Has the COVID-19 pandemic made you reflect differently on For All Who Hunger?

It’s been a kind of ironic time for the book to come out because it’s so much about community connection in this physical, visceral closeness around tables. So I think in some ways that’s been kind of painful because we can’t have that right now. But in another way, I think the book has been able to offer people that experience of feeling close and finding communion, even through the pages of a book, so that’s been really powerful.

Part of the book covers the history and demographics of Gowanus, where St. Lydia is located. It’s home to the Gowanus Canal, a neglected waterway. Can you talk about the canal and the neighborhood it represents?

The canal became representative to me of these different layers of communities that have lived in Brooklyn and are living in Brooklyn. The canal itself has these layers of history that are still visible—it’s so polluted that, when you look at it, you think, “How did we get here?” And if you go and research, you can read all of those layers of abuse back through history, starting with colonialism, when the Lenape Indians were deprived of their land. So, the story of that canal is so deeply rooted in so many layers of sin.

At the same time, it’s the home of this very thriving artistic culture in Brooklyn of artists who come to the city and often—and I include myself as one of these people—as newcomers to the city, almost live on top of the city, on the surface. But if you take a moment to drill down into those layers of story, you start to see, “Oh my goodness, I’m part of a much larger story of this land and this city.” And to be connected to that story started to become so important to me.

One of the stories that I learn [in the book] is of [Nicholas] Naquan Heyward, Jr., this young child who was shot in that neighborhood in the ‘90s. And I think there’s a similar layered quality there—that some of us might be just awakening to racial injustice in the United States, but when you start to look around your neighborhoods and your communities, you start to see, “There are so many layers of sin that I’m standing on at any moment, on any given block.” I think that that process of awakening was a very painful process, but it’s so much better to be awake than to be asleep. It’s better for the world in general and it’s better for our souls, as well.

[St. Lydia] itself moved through this process of awakening and becoming much more connected to the stories of our neighborhood, and being much more deeply rooted in the wider family of God that lived there in Gowanus.

What other aspects of For All Who Hunger are you most excited to be talking about?

Part of my hope for this book was to write a story that it felt like most of my readers—predominately white, predominately mainline Christian and predominately middle class—would identify with, and then to sneak some subject matter in that they might not have necessarily have picked up in the bookstore. When we tell our stories, it allows people to engage something that they might not have considered. It’s really my hope that people will be drawn to the story of St. Lydia’s, but then be opened up to these broader issues around economic injustice and racial injustice.

That’s the most important piece to me, because I think that’s really what God is doing in all of our lives, is this process of awakening and turning over and transformation, that’s drawing us into being more connected and more open to the stories that are around us—the stories of the world and the stories of injustice.