Care for and by children of God in Black skin has a long history in the Lutheran church, despite the impression one might have of the ELCA as currently a predominantly “white” denomination. What follows is a glimpse of significant early Black Lutheran contributions and records.

Historical records show that the first Lutheran baptism of an American of African descent occurred on Palm Sunday in 1669, when a man named Emmanuel was baptized at Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Matthew in New Amsterdam (now New York City).

Not long after, in what is now Ghana, Anton Wilhelm Amo was born around 1700. Taken in 1704 as a slave to Germany, Amo was “gifted” to Anthony Ulrich, duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He was raised in the household with the duke’s sons, attended the universities of Halle, Wittenberg and Jena, and eventually taught at those schools. His first dissertation, loosely translated, was “The Rights of an African in Eighteenth Century Europe” (no copy exists). A second work was “The Apathy of the Human Mind.”

Today at Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, Amo is among the professors commemorated in the quadrangle, alongside reformers Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon.

By 1860, 200 Black members worshiped at St. John Lutheran Church in Charleston, S.C., with a Sunday school of 150 served by 32 teachers.

The congregation of Zion Lutheran, Oldwick, N.J., remembers that their history began in the living room of Aree Van Guinea. He had purchased his and his family’s freedom while in New York City. Van Guinea bought land in the Raritan Valley, in what is now Oldwick. The first worship service, July 14, 1714, was at his house, when Van Guinea invited his pastor, Justus Falckner, to preach to his newly arrived neighbors who were Palatine Germans. Van Guinea deeded a portion of his property to build the first church there, which still stands on a corner in Oldwick.

Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, often described as North America’s Lutheran patriarch, disembarked in Charleston, S.C., in 1742 to serve German immigrants in the colonies. He wondered in his journal whether the large population of Black people he first witnessed in North America had been “saved by grace.” Muhlenberg was aware of the status of Black people in Charleston as he had, during his transatlantic crossing aboard a packet ship, raised a question regarding a Black stowaway. Once in Charleston, he put together a gathering of Lutherans before his departure for Philadelphia. St. John Lutheran Church traces its origin to that early gathering.

John Bachman, after accepting the call to the Charleston congregation in 1815, asked St. John’s leadership whether he could invite Black people into membership. Their affirmation led St. John to include Black congregants in worship and to develop a separate Sunday school. By 1860, 200 Black members worshiped there, with a Sunday school of 150 served by 32 teachers. Bachman also sent three Black men to serve the church in other places.

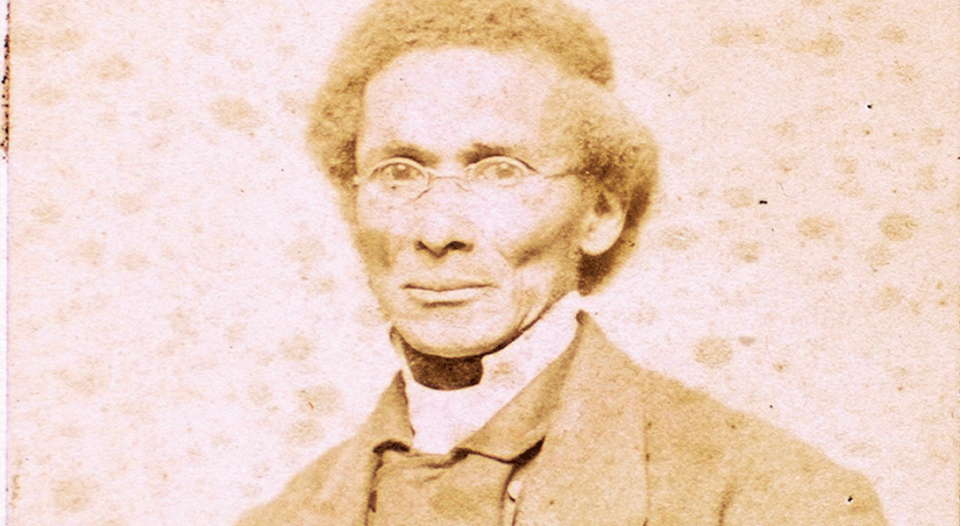

In 1832, Jehu Jones, a 46-year-old freedman, was sent north for certification by the New York Synod, but his age was seen as a detriment to his serving as a missionary to Africa. He thus moved to Philadelphia with his family and started St. Paul Lutheran Church in 1834. He received minimal and sometimes no financial or other support from his colleagues in the city. The undercroft of the church survives inside the University of Pennsylvania’s Mask and Wig Club.

An abolitionist speaker, Daniel Alexander Payne drew the attention of the Franckean Synod—a Lutheran church body formed by pastors who were dissatisfied by the church’s position on slavery—which offered him ordination.

Daniel Alexander Payne, a Black 19-year-old schoolteacher, turned to Bachman, who had written biology books with noted naturalist John Audubon, for advice and information about his future. When Black people were denied the right to teach or run schools in South Carolina, Bachman, among others, gave letters of introduction as they assisted Payne in moving north.

The Mission Society of Gettysburg (Pa.) Seminary offered Payne a scholarship, with the understanding that he did not want to be an ordained minister. An abolitionist speaker, he drew the attention of the Franckean Synod—a Lutheran church body formed in 1837 by New York pastors who were dissatisfied by the church’s position on slavery—which chose to offer him ordination. Within two years Payne had relocated to Philadelphia, reaffiliated with his Methodist roots and became a pastor, bishop and the president of Wilberforce (Ohio) University.

Black leader Boston J. Drayton was ordained by Bachman as a missionary and sent to Liberia in 1845. He started a missionary compound in Maryland (which became part of Liberia). Drayton occasionally returned to seek funds for his efforts. He was even bold enough to go beyond Lutheran sources, thus giving Southern Baptist churches a link to this shared history. He died in 1866 as the chief justice of the Supreme Court of Liberia.

Historical records are spotty during the years of Reconstruction (1863-1877) and in the 1890s, but records can be found to identify the following early contributions by Lutheran Black pastors:

- 1868: Michael Coble is licensed to preach by the North Carolina Synod.

- 1880: J. Koontz is ordained by the General Synod.

- 1884: Nathan Clapp and Samuel Holt are ordained by the North Carolina Synod—but not granted full pastoral privileges nor financial support.

- 1888: William Philo Phifer, educated in Baltimore, is licensed by the Maryland Synod in 1888, received by the North Carolina Synod in 1889 and ordained in 1890.

- 1889: Coble, Koontz, Clapp and Holt, not receiving support from the North Carolina Synod, form the Alpha Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Freedmen in America.

- 1890: Koontz dies.

- 1891: In seeking funds for support, the Synodical Conference sends Nils J. Bakke to supervise. He persuades all to resign, except Phifer, who professes that his ministry is just as valid as Bakke’s. He uses the constitutional autonomy of the congregation to refuse to move.

A grant from the Louisville Foundation is underwriting the author’s research into Black Lutheran history.