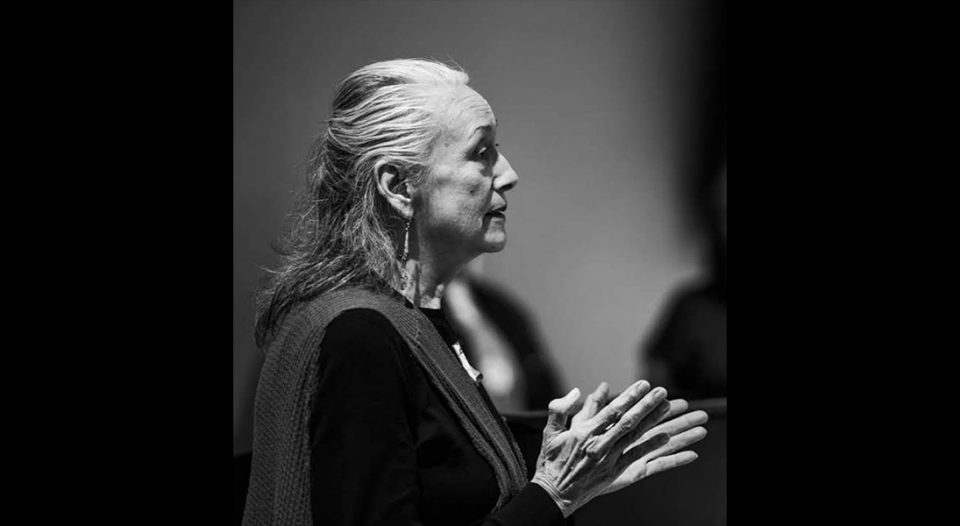

They call her “Big Mama.”

It’s probably not the most common of titles used by church members for their pastors, but it works here.

Mary Louise Frenchman might be “Pastor Frenchman” in professional circles. In more formal settings, some might introduce her as “the Rev. Mary Louise.” But to those who gather for worship and greet her almost daily on the streets of Phoenix, it’s “Big Mama.”

“She is certainly one of our elders,” said Vance Blackfox, ELCA director for Indigenous ministries and tribal relations. “She inspires the rest of us to keep wanting to continue this work.”

That work, for Frenchman, is the Native American Urban Ministry (NAUM), a presence in downtown Phoenix for the last decade. In a city with more than 100,000 people of American Indian ethnicity, this ELCA ministry had been a long time coming—even overdue, some would say.

Big Mama happened to be in right place at the right time.

In fact, Frenchman has been in Phoenix since the 1950s, when her Oglala Lakota parents moved their family off the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota—one of the largest in the country—and south to Phoenix. As did tens of thousands of other American Indians who were “encouraged” by the nation’s Indian Relocation Act of 1956, her family abandoned life on the reservation for promises of a better life in America’s urban centers. For most, it didn’t work out that way.

The ministry today “is not like a ‘regular’ congregation.”

Decades later, an ordained and experienced Frenchman admittedly stayed after the idea arose of restarting a long-absent ministry to American Indian people in Phoenix’s urban center. “It’s just not OK to be in a state with 23 Indian reservations and not have outreach,” she said. So, in 2012, Frenchman began serving as mission developer of NAUM, a ministry sponsored by the Grand Canyon Synod.

The ministry today “is not like a ‘regular’ congregation,” she said. Half of those who gather for worship every other Saturday in the fellowship hall at Grace Lutheran Church are experiencing homelessness. Many of the others—whose tribal lineage includes Hopi, Navajo, Apache and the O’odham people of the Sonoran Desert—are “on the fringe,” she said.

For NAUM, church takes place far outside the church building. “I’m out in the community with people, where they’re at,” said Frenchman, whose training in community organizing long predated her enrollment at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, Berkeley, Calif., in the 1990s.

Any given day at the ministry site might find volunteers sending 50-pound bags of soil home for urban gardeners or teenagers learning together. Some days helpers stock the food pantry. Other days, tribal elders meet and form a circle of chairs for conversation and singing. Every Saturday’s worship concludes with a clothing giveaway to those who need it most.

“This is like Jesus!”

Like many American Indian people of her generation, Frenchman grew up in South Dakota with minimal faith formation. Missionaries permitted little to no inclusion of tribal customs in the worship services they held, and she rarely a saw a clergyperson outside the church building. When she first encountered a Lutheran pastor out among the people in her youth, she said, “I was like ‘Oh, this is like Jesus!’”

That approach has stuck with Frenchman.

NAUM’s services mix traditional Lutheran liturgy with tribal customs as effortlessly as the worship assistants mix sage, oils and other spices with a flame to create the smudging that calls forth confession and forgiveness in a way that many identify with their American Indian heritage.

As the smoke rises from an abalone shell, an older man and a boy fan the scent over waiting worshipers with an eagle feather “to cleanse our aura and prepare our hearts for worship,” Frenchman said.

Smudging is a near-universal custom across American Indian nations. Almost as universal, Frenchman said, is the memory of most native worshipers that churches they had previously known “won’t let them be native.”

“We believe we don’t own anything. We don’t own the church.”

“It’s embarrassing that people would call us ‘savages’ and ‘heathens,’” she said. “We have a deep spirituality that is connected to one Creator. We believe we don’t own anything. We don’t own the church.”

Although she’s never one to utter the word “retirement,” when asked about it, Frenchman has a ready answer: “All my life I’ve wanted to be a grandma who sits around and rocks kids, like in a crisis center.”

Frenchman previously came out of a short-lived retirement to start NAUM. Now, outside of her 45-hour work week, she volunteers in an assisted-living center for patients with traumatic brain injuries. And she has two young great-grandchildren whom she sees every week. They’re the ones who tagged her with the title that has carried over to her professional life.

But that foster grandparent role is something she’s got her eye on when the next “retirement” comes. “They need someone to just love and rock the kids,” she said.

Big Mama, indeed.