When I first met author and theologian Erin S. Lane, we were both voluntarily child-free. Meeting her was a gift to me because, especially in the church, I felt that much of my worth was tied up in my family or perceived lack of one. Though both of us have since taken on mothering roles, the parts of us that aren’t about motherhood are still there.

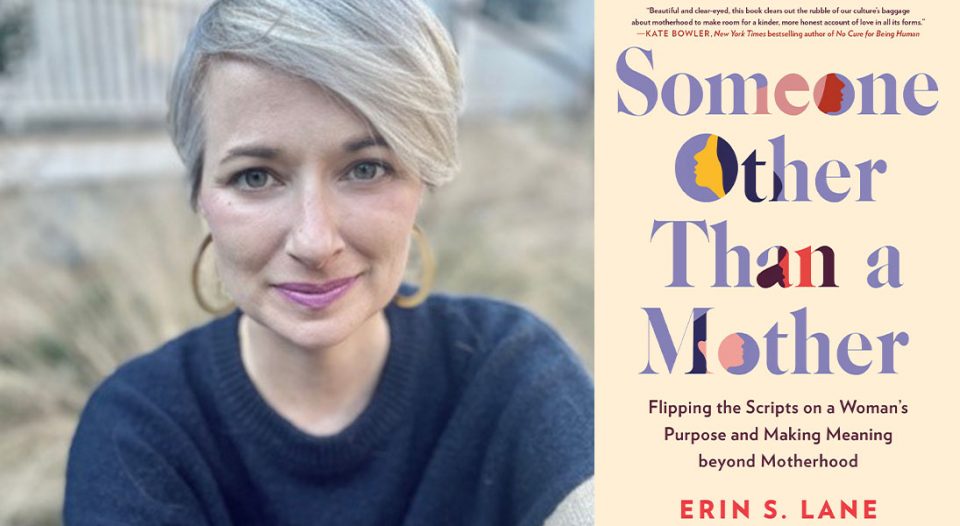

Lane’s new book, Someone Other Than a Mother: Flipping the Scripts on a Woman’s Purpose and Making Meaning Beyond Motherhood (TarcherPerigee, 2022), is also a gift—not only to “nontraditional” mothers or parents but to the rest of us, who may not feel that our lives are defined by those for whom we care.

Living Lutheran caught up with Lane, whose book reminds us that there are many ways to be part of the body of Christ.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about your new book?

Lane: I like to describe Someone Other Than a Mother as a memoir/manifesto for anyone—whether single or coupled, stepparent or foster parent, infertile or ambivalent—who doesn’t feel what they’re supposed to feel about motherhood, traditionally defined. We want a purpose bigger than body parts. We want an identity fuller than children—[our] lack of [them] or love for [them]. We want a legacy larger than our own kin. We do not want to be seen as more mature or immature, selfless or selfish, holy or unholy, than anyone else solely on the basis of our parenting status. Most of all, maybe, we want to set aside the shaming social scripts that are bad for moms and non-moms alike and write a truer, kinder story about who we are when we are not who the world expects.

You weave personal narrative with research and interviews. How did you decide what to include and how to structure the book?

The structure was the easy part. Each chapter centers on a particular social script about motherhood—everything from “Your Biological Clock Is Ticking” to “You’ll Regret Not Having Kids”—and offers a more generous rewrite—like “The Sound of Your Genuine Is Calling” or “Kids Are Not Insurance Policy.” The point is not that these social scripts or pervasive cultural sayings don’t work for some women, but that they’re assumed to be true of all women, thus shaming anyone who lives beyond their cloud of certainty. The hard part was that every chapter could have been its own book!

“If we don’t learn how to disentangle popular “family-first” philosophies from our lived theologies … we’ll diminish our credibility to preach a gospel that says we’re saved not by what we’re able to produce or reproduce but by grace and grace alone.”

What surprised you in your research or writing?

Originally, I thought I was writing a book for non-moms. The title pitched in the proposal was The Non-Mom Manifesto …. But then I realized that what I was really trying to do was write a book that was big enough to include me, a formerly child-free, adoptive mother of three. Soon I realized other women were struggling to fit the pre[fabricated] categories too: “real” moms and surrogate moms, the childless and child-free, “traditional” and “alternative” families. No one in my circles really described themselves using these labels. So, it made me want to try, somehow, to host a more generous conversation in the book [for] any woman who was struggling with the categories. When we came up with the title Someone Other Than a Mother, it finally clicked for me, especially given that “other love,” not specifically “mother love,” is considered the litmus [test for] a life well-lived in spiritual traditions like mine.

Was it easier or harder to write this book now that you’re an adoptive mother rather than a child-free woman by choice?

I want to say easier, because it’s not until I became a parent that I knew, definitively—for myself, at least—that parenting was not the shortcut to enlightenment I’d been sold. And this is the problem. We tell non-moms, “Oh, you don’t know love until you become a mother,” and there’s no good way to refute that other than to ask, with gritted teeth, “And who are you to make a hierarchy of love?”

So, it felt important to say to readers with some authority, look, I’ve been on both sides of these shaming social scripts now, first as a childless woman who didn’t feel capable of the big, exceptional love mothers talked about, then as a child-full woman who didn’t experience the big, exceptional love mothers talked about. And, as I write in the book, I’m now convinced that almost every shred of shame I have swallowed before and after motherhood is not because I don’t love children or my children but because of the insistence that I’m supposed to exceptionally love them, more than anything. Even God.

What do you think members of the church, and Lutherans in particular, need to know about what it is to be someone other than a mother?

I define “someone other than a mother” as anyone who resists the idea that motherhood is a superior source of meaning, identity and love to all the others. At face value, this way of being in the world should be pretty easy for folks in the church to understand, especially given our profession that baptism, not biology, is what binds together the family of God. And yet, the research shows that involvement in religious activities often provides social affirmation of parenthood and social sanctions for those deviating from childbearing norms. For instance, there’s a positive correlation between how often a woman attends worship and how often a woman gives birth—even across denominational lines of difference.

Another study shows that women who are voluntarily childless are more likely than their involuntarily or temporarily childless peers to affiliate with no religious denomination, even after having been raised in one. So, if we don’t learn how to disentangle popular “family-first” philosophies from our lived theologies, not only will we diminish our ability to support a growing number of women who are making meaning beyond motherhood, but we’ll also diminish our credibility to preach a gospel that says we’re saved not by what we’re able to produce or reproduce but by grace and grace alone.