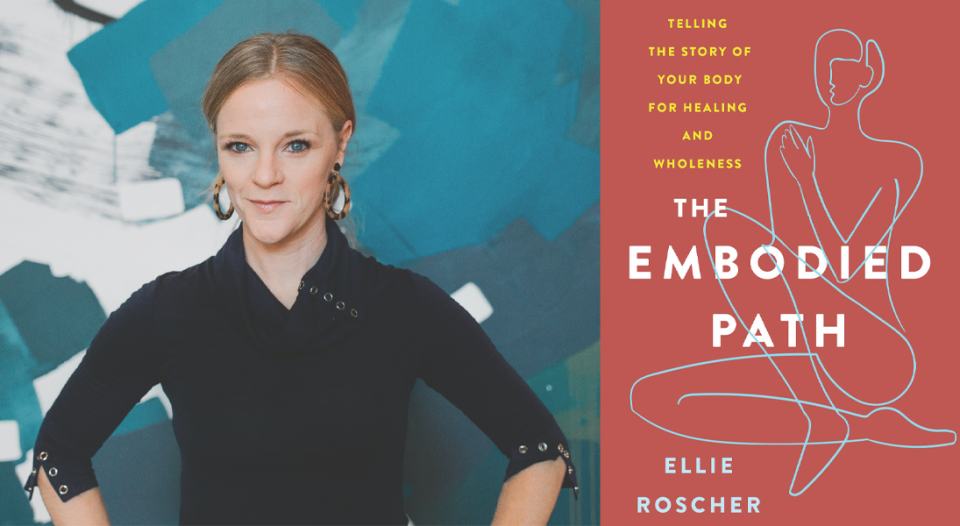

When Ellie Roscher was 13 years old, she dreamed of becoming a gymnastics star. The night before a big meet, a tumbling accident sent her to the emergency room, a story she details in her book The Embodied Path: Telling the Story of Your Body for Healing and Wholeness (Broadleaf Books, 2022).

After her fractured, dislocated elbow healed, Roscher learned that her doctor had almost been forced to amputate her arm. “This book isn’t about what happened to my elbow,” she writes. “This book is about the story I tell about what happened to my elbow, and how that story has helped me live a more embodied life.”

Alongside her stories, Roscher highlights more than 20 body stories from people with varied backgrounds. She hopes the collection will enlighten readers’ understanding of their neighbors and empower readers to claim their body stories.

Living Lutheran connected with the ELCA member and author to discuss her latest book.

Living Lutheran: Who is your book for, and what do you hope it will do?

Roscher: The Embodied Path is for everybody. I think it’s going to [resonate] with people who work with bodies for their jobs—teachers and nurses. Every person has a body, and [the book is] inviting people to be tender and compassionate with theirs; to explore all their bodies have been through and to honor their resilience; to notice the ways their bodies have been policed [and] the ways they are privileged; to explore ways we take our bodies for granted.

One of the things the book is going to do is help us think about how we can do community better so that all bodies feel a sense of safety and belonging. We’re at a tipping point now when we understand trauma happens in the body. Where does narrative play into that? Can there be narrative repair?

Tell us about your book’s title. What is the embodied path?

My body experience is that there’s invitations all the time to live in my mind. The embodied path is carving out neural pathways to drop back down into the body. Three of my paths back home to my body have been my breath, movement and writing. That’s why the book has breath practices, body breaks and writing prompts. Inhabiting our bodies is part of our vocation.

I hope readers see their bodies reflected in the book somewhere and [take it] as an invitation to step into their stories. They have to have agency to do it. I created Plum as a place for people to land after reading it. It’s a safe online community where people can breathe, move and write together. My vision is that it can be one place to share body stories in a way that [feels] generative and healing.

Why did you write this book?

Since I was 13, I’ve been really conscious that I had two arms and I had a body. My injury introduced that to me. I felt in one moment how shifting my story about my elbow shifted my sense of freedom and agency.

Jesus’ ministry was about restoring bodies.

When I would preach or write about my experience and embodiment, people would ask me to do that more. People also told me stories about their bodies. My life got more complicated hearing about different bodies. I have so much body privilege; I want to listen to people who have had a different body experience in society.

Every body is limited, and we’re interdependent and all need each other, but we cast away certain bodies. I experienced that as a mother. When [moms] get back to work [after having a baby, society] just wants [them] to be “normal.” What would happen if there’s no back to normal? What if society could learn from how mothers break open and grow and expand?

You share vulnerable stories of your body in this book and elevate the stories of others with bodies and backgrounds different from yours. Why are body stories important?

The personal stories I shared in this book were stories I was ready to attach words to. Writing about [my miscarriages] brought a lot of emotional healing. Miscarriage is so common. You’d never know because [the church doesn’t] have a liturgy around it. This is a grief that’s highly invisible. The shame falls away by naming it.

As I was telling my story, I wanted to listen to others’ stories. I wanted a diversity of bodies telling stories so that readers could connect in somewhere. We need to intentionally put ourselves in the path of other bodies who are different from ours.

We live in a society that pressures us to be very cruel to our bodies and to each others’ bodies. When we speak our truth, our stories build empathy and connection. By naming and claiming what our bodies have been through, that’s going to activate us as members of churches and society.

What can the church glean from this book?

I’m hoping for this to be a tool, a place to start. I’ve created a faith guide that is a supplement, including seven Bible stories that go with seven chapters of the book.

We have this history in the church of being deeply disembodied. Trusting the wisdom of our bodies is spiritual work. When we can speak our truth, our stories work to build empathy and connection.

God took on a body in Jesus. God knows what it’s like to be embodied and to experience body limitations. Jesus’ ministry was about restoring bodies. [I hope readers] turn toward their body with curiosity and reverence and know it is something very good and powerful and extremely resilient.