My middle daughter, Marta, is 4 feet, 11 inches tall. In 1988 my wife and I adopted her from a Roman Catholic orphanage in San Salvador when she was 11 months old. Sadly, the orphanage was destroyed in an earthquake a few years later. From a distance, Marta has always felt a close kinship to the children who died in the tragedy and to her Mayan birth parents whom she will never meet due to the almost nonexistent records we received from the public hospital in the city.

Marta has always loved the story of Zacchaeus, who climbed a sycamore tree to get a better look at Jesus. We read her board books at an early age featuring the diminutive tax collector and his precarious climb out onto the branches.

I was reading the story of Zacchaeus the other day (late in the church year) and was reminded of an interesting twist affirmed by several early church commentators. The pronoun at the end of Luke 19:3 (in English and Greek) is provocatively ambiguous: “because he was short in stature.” Exactly who was short in stature?

Take a look at the story again and read it slowly. A compelling case can be made that Jesus (not Zacchaeus) was difficult to see because of his relatively short height, especially when surrounded by a crowd in a town such as Jericho. The tax collector climbed a tree to get a better look at the teacher who was all but invisible at ground level, swallowed by folk hanging on his every word.

If this is true, that Jesus (not Zacchaeus) is the fairly short man requiring sycamore assistance for a potential convert to properly view, then lots of Bible images explode in my imagination beyond the possibility of the Lord of heaven and earth resembling a sassy Danny DeVito.

It may explain how Jesus was consistently able to hide from enemies who wanted him dead. It may suggest why Judas needed to kiss and identify a surprising troublemaker when soldiers may have been expecting a more formidable enemy. And it certainly fits the proclivities of God whose thoughts are not ours (Isaiah 55:8) and who consistently chooses unexpected venues for revelation, including an unlikely Bethlehem barn.

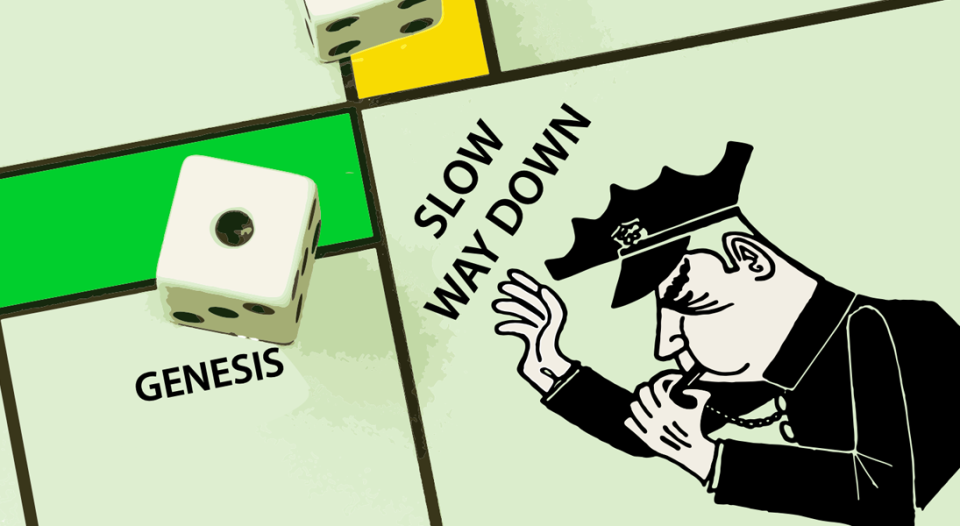

The Bible is an enchantingly bizarre library of bound books. The evening news comes at us fast and furiously and includes distracting zippy commercials. The Bible requires serious readers to slow down, way down, so they can unveil its surprising truth.

Bible interpretation is at least as mind-bending as a challenging board game, requiring patience, attention, creative thinking, even risk.

This isn’t an easy enterprise for a distracted nation (and church) such as ours. “The Bible may be difficult and confusing,” Thomas Merton wrote in Opening the Bible, “but it is meant to challenge our intelligence, not insult it.” Reading Scripture is not an easy “express insight” enterprise. Truth in the Bible is often mined, percolated, sifted and examined from multiple angles.

A daily reader of the Bible for 35 years, I’m now convinced this was an on-purpose recurring intention authored by the surprising Spirit who inspired its writers. I’m not talking about intentional obfuscation, so fuzzy that only academics can decipher the Bible’s “true” meaning. I’m saying that Bible interpretation is at least as mind-bending as a challenging board game, requiring patience, attention, creative thinking, even risk.

There is a great scene in the movie Smoke (1995), set in New York City. A tobacco shop owner named Auggie (Harvey Keitel) has the curious habit of taking a photograph outside his shop each morning at the exact same time. Each day of the year—same time in all sorts of weather—he never misses. Auggie has dozens of albums with these photos, covering decades of time. One night in his apartment, Auggie shows the album to his writer friend, Paul (William Hurt), who is suffering from writer’s block after an accident.

Paul flips through the album pages quickly, laughs and says, “They’re all the same.” Auggie begins to gather up his photos, a bit offended. “No, you’re missing it. You’ll miss the point if you look at them that way. You’ll miss the people. All these people who have come to my little corner in this little part of the world. And you’ll miss the light. How the earth turns at different times of the year. How the sun hits my corner at a different angle in the spring from the fall. You may as well not look at them if you’re gonna go that fast.”

Wise congregations will adopt the thinking of Auggie as they plan ministries introducing new adult Christians to the power and depth of the Bible. The church’s book isn’t filled with stories at which a mature Christian simply glances.

It took me a while, for example, to discover that Jesus is something of a tease in the Gospels. This isn’t apparent in examining the life of a man who seems utterly serious at first glance and who offers no scene of laughter to be recorded in the Bible. Jesus, however, knew all about humor and had impeccable timing.

Cleopas and an unnamed friend walk away from Jerusalem, apparently punting the early church community. “We had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21). A third man appears and walks along, seemingly unaware of the sadness that’s recently occurred on a hill outside the city. Stunned, Cleopas is curt with the newcomer: “Are you the only stranger in Jerusalem unaware of these things?”

Even something as small as punctuation choice matters in the slow percolation of biblical truth.

Perhaps Jesus waited a few seconds to answer. But take a moment to sound out his reply and let it sink in. “What things?” Two words. One small question. Seinfeld couldn’t have staged it better.

It also took me a while to notice tiny bits of Bible data that often unlock new worlds of interpretation. Consider Peter’s speech to gathered believers just before Pentecost in the first-century equivalent of the church announcement period during worship. Peter is explaining the treachery of Judas and his grisly demise (Acts 1:15-19). The original Greek includes no punctuation. But a slow interpretive guess on the boundaries of Peter’s speech reveals fascinating possibilities. The New Revised Standard Version interrupts Peter’s words after verse 17 and then includes a couple of graphic parenthetical sentences describing Judas’ bowels.

Interestingly, the Revised Standard Version (RSV) chooses to include the bowel-gushing within Peter’s speech! An R-rated announcement by the presiding minister in the gathered assembly.

Well, which punctuation choice does the patient interpreter make? Personally, I like the unsanitized RSV approach that might lead to more transparent honesty on Sunday mornings for clergy like me who tend to protect parishioners from the nitty-gritty of church life.

But the main point: even something as small as punctuation choice matters in the slow percolation of biblical truth.

A few months ago, my wife and I vacationed with another couple on Smith Mountain Lake in Virginia. They brought a competitive board game called “Wingspan” that we played one rainy day. The game teaches avian habits and requires a mindful balancing of eggs, food tokens and bird cards. Our friends patiently explained the rules. I played the game and had to lie down on the floor for a nap. The game is brain-taxing and mine was toast. I suspect one must play “Wingspan” multiple times to get any good at it.

American Rabbi Burton Visotzky, in Reading the Book: Making the Bible a Timeless Text (Schocken Books, 1996), writes that reading God’s word is “an adventure, a journey to a grand palace with many great and awesome halls, banquet rooms, and chambers, as well as many passages and locked doors. The adventure lay in learning the secrets of the palace, unlocking all the doors and perhaps catching a glimpse of the King in all his splendor.”

Zacchaeus once went out of his way and patiently climbed a tree—perhaps through tangled branches—to get a glimpse. It made all the difference.