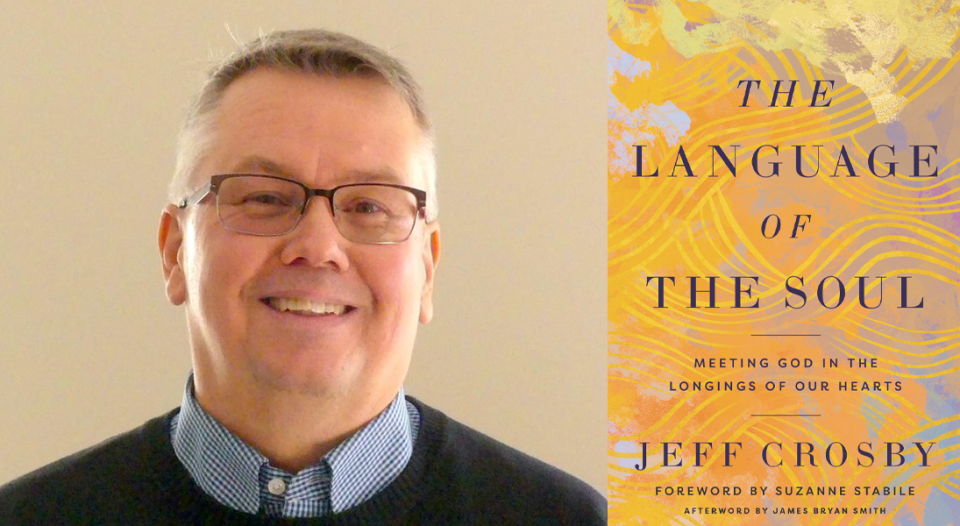

For years Jeff Crosby searched for ways to articulate the human longings and unanswered yearnings that language often can’t express. In his search he gathered clues from music, cultures, faith traditions and sacred texts from around the world. His new book, The Language of the Soul: Meeting God in the Longings of Our Hearts (Broadleaf Books, 2023), explores how those longings can provide profound opportunities to connect with God.

Living Lutheran spoke with Crosby, president and CEO of the Evangelical Christian Publishers Association and a member of Faith Lutheran Church in Glen Ellyn, Ill., about the book’s themes and their connection to his identity as an ELCA Lutheran.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about The Language of the Soul?

Crosby: It’s a brief, accessible work of spirituality that explores 10 “longings of the human heart”—from home to heaven—that I believe are common to most if not all of us as people made in the image of God. It also illustrates, through stories, the ways in which we are met in the midst of them in ways both ordinary and extraordinary.

How did you decide to write a book on this topic?

It’s a book I’ve been working on for more than 15 years—I don’t recommend waiting that long to publish, by the way—as a means of understanding the stirrings of my own heart through seasons of change, loss, transformation, growth.

Much of it began as journal entries where I was attempting to be attentive to what was happening in my soul and gain greater understanding of both internal and external longings I identified there. But during the spring of 2020, when the pandemic upended so much of life, I leaned into it with greater energy, believing the time was right to share my reflections about a longing for friendship, for community, for freedom from fear and anxiety and more.

The book explores the concept of saudades. Could you explain that term?

The word saudade is a Portuguese word that linguists call an “untranslatable emotion.” There is no direct translation into English. It came to me originally through jazz, bossa nova and fado music arising out of Brazil and Portugal, and musicians such as João Gilberto, Ivan Lins, Yo-Yo Ma, Chris Rea, Ivan Lins, Oscar Castro-Neves and others.

All the pieces fit together into a beautiful tapestry that wasn’t just individualistic but was communal.

Most English writers and thinkers equate saudade with our English notion of longing. Although I’ve worked in the world of publishing all of my adult life, music is the language of my soul. So the book brought together those two things—books and music—into one cover as I wrote about spiritual longings.

You share in the book how God met you in your longing for a spiritual home through your congregation. How did the worship experience there offer that for you?

When my wife and I joined our ELCA congregation nearly 15 years ago, we came from a decidedly nonliturgical background and also a spiritual context that was much more focused on an individual response to the gospel. When we came to Faith Lutheran Church, I recall having a sense—paraphrasing John Denver’s “Rocky Mountain High”—that I’d “come home to a place I’d never been before.” It was as if I instinctively saw how all the pieces fit together into a beautiful tapestry that wasn’t just individualistic but was communal.

The church cared about the proclamation of the gospel, yes, but it also cared about social justice. It cared about ecology, about climate change. It cared about racial reconciliation. It cared about all human persons made in the image of God. Our observance of the church year brought a rhythm of reflection and joy to each passing season, which was another gift. And most of all it was the eucharist—kneeling at the rail, receiving the bread and wine—that was a weekly reminder that God is—that God is present in our world, despite all of the division and anger and injustice and needs all around us.

How have you found that Lutheran theology aligns with the pathways for getting in touch with the feelings of longing you describe?

Martin Luther esteemed music highly, as we all know. So I would begin there—that the lyrical and musical aspects of the book will feel familiar and will draw readers in. I also write in various places about practices, such as praying the psalms and doing a Daily Examen, that are reflected in our worship liturgy within our congregations. The assurance of forgiveness is another point of alignment. [And] ultimately, our theological embrace of grace, of the sufficiency of Christ, of the importance of Scripture.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

In his book The Holy Longing, the writer Ronald Rolheiser said that what we do with our longings—both the pain and the hope they bring—that is our spirituality. My hope is that The Language of the Soul will help Lutheran readers—and others—be attuned to their own longings, and find hope, peace and joy in the midst of them.