In the days following George Floyd’s murder, the eyes of the world were on the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue in Minneapolis. The corner where Floyd was killed by police in May 2020 became the epicenter of a passionate local uprising around racial justice, leading to the largest protest movement in American history. One block away from the corner now known as George Floyd Square stood Calvary Lutheran Church, where Shari Seifert, president of the European Descent Lutheran Association for Racial Justice, is a member.

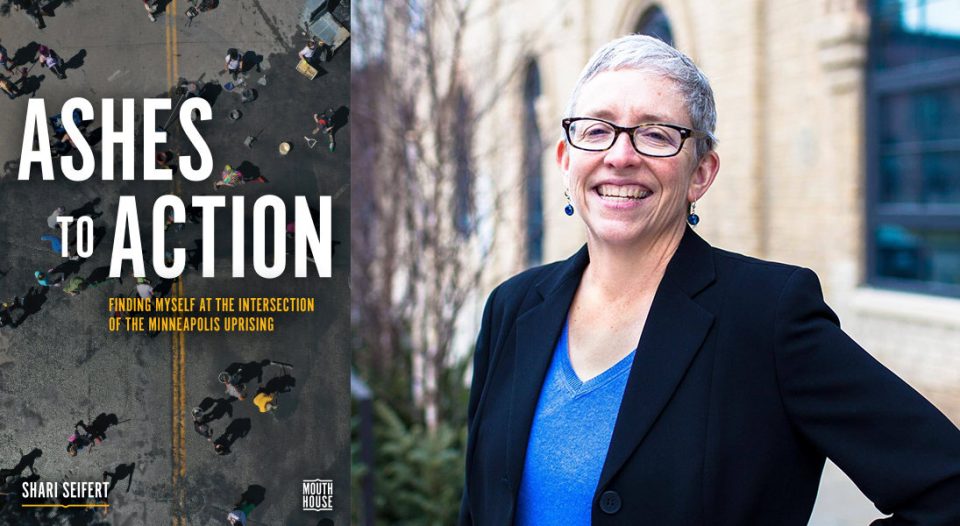

In her new book, Ashes to Action: Finding Myself at the Intersection of the Minneapolis Uprising, Seifert offers a powerful on-the-ground account, and a moving description, of the way she and others from Calvary lived out its mission as the church in their community in the weeks and months after the uprising began.

Living Lutheran spoke with Seifert about Ashes to Action, part of Augsburg Fortress’ new “Mouth House” book series. Inspired by Martin Luther’s declaration that “the church is a mouth house, not a pen house,” the series aims to compel readers to move beyond the written word into deeper conversations and meaningful action in their communities.

Living Lutheran: How did you decide to write this book?

Seifert: I was asked to speak about the events following the murder of George Floyd several times, and I found that I was forgetting some of the details. I think the story of how and why my congregation was able to respond as things unfolded following the death of George Floyd is an important one, so I decided that it was important to write it down. I hope that our story and my book can help other ELCA congregations get ready to meet the moments of racial injustice happening in and around their churches.

One of the centerpieces of Calvary’s response to the moment and to your community was the idea of the Community Table. Could you tell readers about what this entailed?

The Community Table was such a beautiful thing! Because we are so well-practiced at protests in Minneapolis and so many people were outraged by the callous murder of George Floyd, people showed up with an abundance of food and beverages at the first protest march, launched out of the Calvary parking lot. We ended up storing huge quantities of these supplies in our narthex after the march was over.

This experience of losing our walls and having permeable boundaries with the neighborhood allowed us to be the church we were always meant to be.

The next day, streams of hot, thirsty and hungry people started to come to pay respects to George Floyd and walked right by Calvary. It just made sense to pull out some tables and chairs and share the abundance. Calvary members and other volunteers staffed the table for many hours a day, so there was time for deep conversation without any agenda.

This lack of an agenda, and the fact that we were just sharing the abundance shared with us, meant that there was not a power differential—we were just together as people, and a lot of amazing conversations happened. I often wonder if this could be replicated in other places, this simple idea of having a table with food and beverages to offer passersby without an agenda.

Along those lines, you reference the notion that when congregations tell their communities, “Our doors are open,” it puts the onus on those “outside” the church to enter on the congregations’ terms, rather than on congregations connecting with their communities by meeting their needs. How has that distinction impacted Calvary’s ministry?

I’m just a street theologian—I have never been to seminary—but I believe this experience of losing our walls and having permeable boundaries with the neighborhood allowed us to be the church we were always meant to be. Calvary has served the surrounding community before [the uprising], but this feels different. There are more genuine relationships.

We knew we needed to just show up and listen first and move in relationship with our neighbors. It’s really pretty simple: Get to know people in the community. [Determine] what are the needs and what are the gifts, and act accordingly. It’s important to show up with humility and a readiness to receive gifts of community and to not assume a savior role. As one elder [at Calvary] recently said, “We are doing church in a new way.”

I personally feel extremely blessed to be part of the Calvary community and the community at George Floyd Square and have felt the nearness of God both at the square and “in church.” I think the impact of our recent experiences has informed our decision to focus on nurturing relationships with three communities: One, those involved with our food shelf; two, our fellow tenants, when we move back into our building that is being transformed for deeply affordable housing; and three, the community at George Floyd Square. For Martin Luther the most important thing was care for the neighbor. It is a joy to live into that call.

Doing anti-racism work and renouncing evil is part of being faithful—it is part of our baptismal calling.

We also have a broader view of who Calvary belongs to and who belongs to Calvary. It goes beyond who the baptized members are and includes the guy who used to play basketball in the Calvary gym 40 years ago.

As you mentioned, one of the ways that’s been true is through Calvary’s building being converted to deeply affordable housing, meaning units that are available at or lower than 30% of the area median income. Could you tell readers—perhaps especially those who are facing similar questions of how to best use their congregations’ spaces—about that?

Like many other churches, Calvary had an aging building that was way too big for us, needed a lot of repairs and was more than we could afford. After many years of deficit spending and a dwindling account balance, we knew we needed to make a change.

We explored sharing space with other congregations, and nothing quite worked. Having building partners that shared our building did not improve our financial situation. We worked with a consultant and started to explore the idea of selling part of our building to a nonprofit developer of deeply affordable housing. The numbers didn’t work for a partial sale, and the idea emerged to sell the whole property and be able to use the building, rent-free, as a tenant.

Being able to stay in our building and helping to provide deeply affordable housing to our neighbors who desperately needed it seemed like a miracle. Being clear that we wanted what was best for our neighbors before diving into the process of selling our building was important and helped guide us to making this faithful move.

You have a chapter specifically addressed to ELCA Lutherans. How do you hope ELCA readers engage with the book?

A big reason that I wrote this book is that I want other ELCA congregations to be ready when the next George Floyd is murdered a block from their church. I hope ELCA readers think about how things we learned at Calvary may be helpful to them in their congregation: What would it look like for them to have a Community Table?

In the last chapter I encourage readers to remember their baptism, to think about Jesus and to lean into their Lutheran roots and theology. I want people to understand that doing anti-racism work and renouncing evil is part of being faithful—it is part of our baptismal calling. For my white siblings, I want you to understand that you need liberation from white supremacy too. I encourage people to join or start an anti-racism team in their congregation or synod. This work is impossible to [do] alone. Read the book for more ideas!