From almost the very beginning of our children’s lives, we invite them to make art: crayons, markers, paints and so many pieces of paper. When they get older, we encourage other kinds of creativity, whether in music, dance, writing or something else entirely.

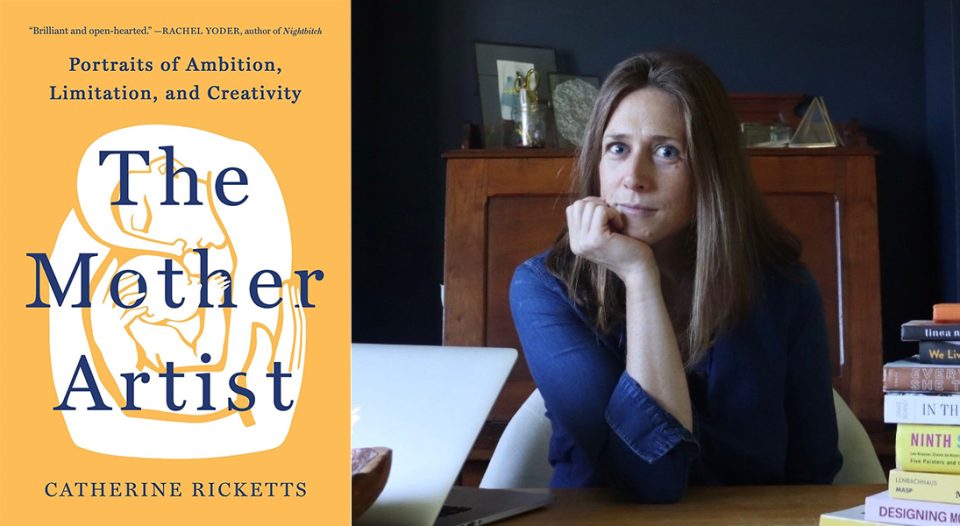

Catherine Ricketts’ new book The Mother Artist: Portraits of Ambition, Limitation, and Creativity (Broadleaf Books, 2024) uses her own story and those of other artists who are mothers to explore what art can look like when it’s not only created by the child but by the parent as well.

Readers who have felt the tension between their own creativity and their roles as parents, or who once found creating art fulfilling but have struggled with it since becoming parents, can find in The Mother Artist encouragement to claim time for their own creative work—either once again or for the first time. Living Lutheran spoke with Ricketts about her book.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about The Mother Artist?

Ricketts: The Mother Artist explores how art-making and caregiving are at play and at odds in the lives of modern and contemporary women artists who had children. I started writing it while working at a big art museum in the earliest days of motherhood. Before becoming a parent I knew that few women artists feature prominently in the history of art, but I began to see that, of the few names that did go down in history—Mary Cassatt, Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, for example—none were mothers.

I began a quest to surround myself with art made by mothers.

As a writer struggling to return to my own creative practice amid the demands of caregiving, I started to wonder about the compatibility of motherhood with creative work and began a quest to surround myself with art made by mothers. I was introduced to visionary, ambitious women who not only persisted through the bodily, economic and social difficulties of pursuing a creative career while parenting but who also found that motherhood enriched their practice. Blending memoir with studies of their work and lives, this book brings readers into this vibrant community of women.

Both parenthood and making art have creativity at their core—and our creativity as humans mimics God’s. How do each of these seemingly disconnected pursuits and their interplay inform your faith?

Art is one of the “means of grace” that connects me most to God. I have long been drawn into worship because of the skill and beauty of a work of culture made by a person that makes me think, “God made humans with the capacity to make this?” Now, having formed two—soon three—children from my own flesh, I am struck with the same sense of awe for humanity’s God-given creative power.

How can the church better care about mothers and their creativity?

Artists help us to see the world in ways that we otherwise wouldn’t. And what an artist looks at shapes the world that she shows us in her work. Mothers spend hours and hours looking at the vulnerable among us, and this can have a particular effect on the way they see the world. I’ve come to call this effect maternal humanism: when a mother looks up from the consuming work of caregiving to see not only her own children but all people as inherently worthy of care, curiosity and delight. Our world, so often marked by brutality, needs art forged through this vision.

Art is one of the “means of grace” that connects me most to God.

Churches can support mothers making art by creating opportunities for artists to create new work and connect with audiences. Commission new music, visual art, writing or performance during high seasons in the liturgical year; host performances; offer resources for artist retreats. And be mindful that one of the greatest barriers for mothers making art is economic; it usually doesn’t add up to pay for child care in order to do creative work, so be sure to pay artists fairly, even abundantly, for their work.

What artists of faith inspire you with their relationship to parenthood and creative work?

The novelist Marilynne Robinson comes to mind. I love how she writes the [titular character in the novel Jack]. By all accounts, Jack Boughton is an intensely lonely, self-loathing and disappointing person. But Robinson writes him with unwavering love. It seems to me that her love for Jack, in spite of all of his failures, is rooted both in her Christian vision of human dignity and in her experience as a mother and grandmother. Robinson loves Jack the way a mother loves even the most deviant of her children: always loving, hoping and believing in their best.

What would you say to an artist embarking on motherhood or a mother embarking on artistic endeavors?

Keep making. Our world needs your unique vision, shaped in caregiving.

What are your hopes for readers of The Mother Artist?

I hope that women who have been struggling to sustain a creative practice while parenting will pick it up again. Maybe they’ll do so immediately. Maybe they’ll remember this book in 15 years, when their kids are more independent, and resume their practice then. No matter the timing, I hope that because of this book, more mothers will return to the work of making and shaping culture. So much is gained when we see the world through their eyes.