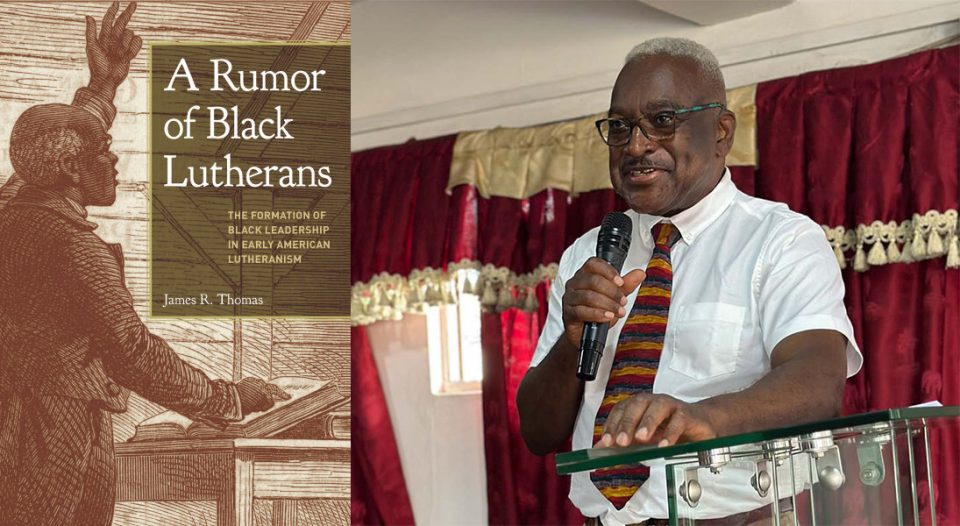

The important contributions of African American leaders to the story of Lutheranism in the United States has a regrettably under-documented history. James R. Thomas’ new book A Rumor of Black Lutherans: The Formation of Black Leadership in Early American Lutheranism (Fortress Press) aims to change that.

By tracing the stories of 10 leaders of African descent whose ministry and service shaped the Lutheran church, Thomas allows Lutherans and general students of U.S. religious history to have, in his words, “a more expansive understanding of Lutheran history.” Unfortunately, many of the painful experiences of the leaders Thomas profiles will feel familiar to African American Lutherans who continue to lead our predominantly white church at all levels today.

Living Lutheran spoke with Thomas about how he came to write the book, the findings in his research that made the biggest impact on him, and his hopes for the book’s readers.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about A Rumor of Black Lutherans?

Thomas: A Rumor of Black Lutherans invites readers to celebrate the lives, faith, courage and resilience of Black Lutherans in the USA. While the narrative does not reach as far back as the Dutch settlement of New York, where Black Lutherans were present, it does remind readers that Blacks have been present in United States Lutheranism for a long time, and their lives and work matter.

How did you decide to write the book?

In the early 1980s, while I was studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York, a [student] colleague bemusedly said, “I’ve heard rumors of Black Lutherans.” Over the years, I came to realize that Black faces in Lutheranism represent 52% of the global membership—when African Lutheranism is factored in—and the rumor is true. My response that day was that I do not know why Blacks collectively choose to join with white Lutherans, but Blacks have been a part of Lutheranism in the United States from the very beginning. The comment by a classmate at Union Seminary remained with me throughout the years and finally became the title of this book.

How did you determine the 10 leaders you profile in the book?

When I undertook studies for my Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota in the 1990s, I was interested in the success of Lutherans in founding parochial and college-grade schools in the African American context in the mid-19th century. As part of my research, I interviewed several individuals who were graduates of schools established by U.S. Lutherans for Blacks. Those interviews became the core for this book. However, to achieve a historical and gender balance, I reached further into the Black Lutheran equational experience and found others. I looked for a thread or a connection between the leaders profiled, and in most cases, I found one.

What were some of the most impactful things you learned about these pioneers as you researched them?

Jehu and Edward Jones came from the same privileged background. Jehu studied under the tutelage of the Rev. John Bachman at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Edward Jones, Jehu’s brother, was the first African American graduate of Amherst College, in Amherst, Massachusetts. The Episcopal Church properly prepared Edward for the challenges of ministry. Jehu Jones, the first ordained Black Lutheran pastor, was not prepared for the work he was asked to do. Edward Jones was accepted as an Episcopal priest and flourished in a career that included serving as a college president in Sierra Leone. Jehu was neither welcomed, accepted nor supported by white Lutheran pastors. The experience of the two brothers provides a clear contrast between Episcopalians and Lutherans.

The book invites readers to celebrate the lives, faith, courage and resilience of Black Lutherans in the United States.

Bishop Nelson Trout styled himself as a liberation theologian. Yet he struggled to articulate a straightforward approach to the LGBTQIA+ community under his care as bishop of the South Pacific District. When he was not elected a bishop in the new Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, he attributed his defeat to his political views and unapologetic stance on liberation theology. One wonders if Trout’s understanding and thinking about LGBTQIA+ matters lost him the support of this community.

Cheryl Pero [was] the first African American woman to complete a degree in New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology [at] Chicago. In 2013, her book Liberation from Empire was published by Peter Lang. Yet Cheryl expressed bitterness and lament at some of her experiences at LSTC. She felt overlooked, ignored, insulted and marginalized by members of the faculty, and “mostly white women.” Cheryl is a reminder that Black suffering may occur in the church, even with a Ph.D. in hand.

Bishop Will Herzfeld worked hard and long, and unto his dying day, for the Lutheran church in the USA. A pastor, church administrator, bishop and ELCA Global Mission executive, one might say that Will seemed to be in all places at the same time. Another word for that is ubiquitous. The warning here is that even the church can use every breath of your life if you are not careful. Will contracted cerebral malaria while representing the ELCA in the Central African Republic in 2002 and died.

Sister Emma Francis is overlooked as one whose life rightly should be commemorated by the church. Here is a woman who took her money to help establish a congregation in Harlem. Almost 100 years later, Transfiguration Lutheran Church, which she helped found, was sold in 2023 by the Metropolitan New York Synod for $3.5 million.

How do you hope readers, in the ELCA or otherwise, will engage with the book?

I hope readers will leave the volume with a more expansive understanding of Lutheran history and what contributes to contemporary reflections about Lutheran identity, cultural thinking and context.