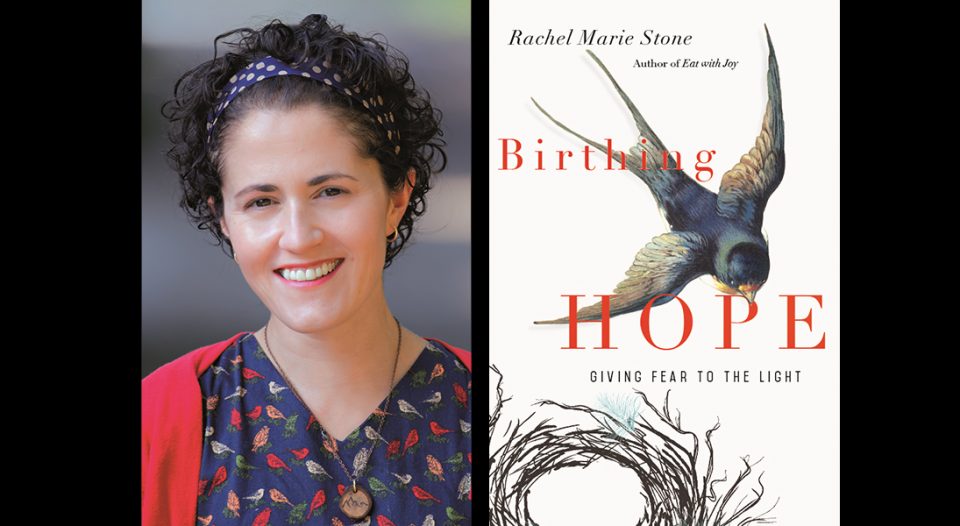

On the surface, Rachel Marie Stone’s new book, Birthing Hope: Giving Fear to the Light (IVP, 2018), is about parenthood and the challenges of giving birth around the world. But below the surface is a universal message about living in the world bravely—even though there might be many things to fear.

Living Lutheran spoke with Stone to go behind the scenes on her new release.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us a bit about Birthing Hope and how you came to write it?

Stone: Originally, I thought this was going to be about maternal health—almost medical reporting or a straight-up social justice diatribe about the tragedy and travesty that is maternal health care—not just in the majority world, in developing nations, but also for women of color and women who are poor in the United States. What the book is about, though, is more than just birth. It’s actually about fear, because birth is a momentous thing, and any big thing, any hard thing that’s worth doing, is not unadulterated joy or unadulterated fear.

I came to realize that is what it is to embrace life fully: to realize that we can’t necessarily numb ourselves out for the hard parts, and we can’t eliminate risk. We can’t always just sleep through it, nor should we always want to get the “emotional epidural.” There is value and goodness in embracing the whole catastrophe of what is. So that’s really what the book is. It’s not just for women, and it’s certainly not only for women who have given birth. It’s really for the anxious, and it’s about [the question of] “How do we live fully in a world where nothing is guaranteed?”

One of the book’s central themes is the way parenthood and other creative acts are entwined with fear. Would you talk about what that link has meant to you and your faith?

We live in a very safety-conscious culture, and I think there’s this idea that we can eliminate risk. We think that if we plan carefully, if we take our vitamins, if we eat perfectly, in a way, we think we can evade death. A lot of the things that [relate to] birth in this culture are just because we’re so afraid of death. A lot of the things that keep us very safe also keep us rather unhappy and isolated. I think we have to expand our notion of what safety is—maybe that’s the wrong focus. Maybe the focus should be on wellness and wholeness. For me, it’s about shifting away from being afraid and trying to stay safe into living a life that’s meaningful and, by nature, involves some risk.

We need concepts of God that can speak to us in a fresh way, especially when we think of the things that Jesus emphasized, like gentleness and accompanying people in hard times—that is a midwife.

The idea of the grace of God should give us tremendous freedom. The notion of grace is that you don’t have to earn approval; you are already beloved, already approved. … There’s a line from my [Episcopal] priest that I quote toward the end of the book: she said faith should be like buoyancy. When you’re in water, you have freedom to move, and you’re also supported by water. I thought that was beautiful.

In your book, and in Scripture, God is portrayed as a laboring mother. How has this image of God informed your faith?

I read a fantastic book a couple of years ago called Mourner, Mother, Midwife (Westminster John Knox Press, 2012) by L. Juliana M. Claassens. It’s about reconceiving God using some of the lesser-celebrated images in the Bible. For Israel, God as warrior was important as a metaphor because they were small and beleaguered and could not fight for themselves. But for the United States, we are already the biggest [and strongest] in the room. We don’t need God as a warrior, fighting for us. We do need concepts of God that can speak to us in a fresh way, especially when we think of the things that Jesus emphasized, like gentleness and accompanying people in hard times—that is a midwife. A midwife is one who helps one through.

I’m speaking in ideal terms here, but at the very least, any of us existing are here because some woman was hospitable with her body and let us live there for nine months, more or less. A good mother raises you when you’re helpless, but then lets you go. It would be a bad mother who would keep you and smother you and make you live out her desires, which we all know some mothers do. If we think of God as [the] ideal mother, God gives birth to us; God is hospitable; God gives us life; and then God ultimately gives us freedom as well.