Series editor’s note: Throughout 2020, “Deeper understandings” will engage the ELCA’s commitment to authentic diversity.

—Kathryn A. Kleinhans, dean of Trinity Lutheran Seminary at Capital University, Columbus, Ohio

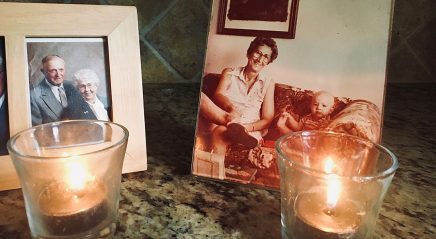

This month we will gather—perhaps virtually—and raise our voices to the triumphant strains of “For All the Saints,” celebrating the company of believers who “from their labors rest.” This year, some will experience an acute, recent pang as COVID-19 marks families and communities. In times past, we might have met in our sanctuaries with a photo of a relative and lit a candle in their memory. This year, sorrow and hope will mingle on our screens as we hear about the great multitude worshiping before God’s throne.

Throughout the United States, Latinx communities—especially Mexican Americans—have grown to the extent that retailers have discovered the windfalls of Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). Many of us have seen the Disney film Coco, after all: sugar skulls, marigolds, picnics at a loved one’s grave and the belief that they visit us during this thin time between worlds. It’s easy to see it as another day reuniting families, even from beyond the veil.

Yet neither Latin Americans nor Latinx communities are a monolith. Different cultures have found various ways to observe Día de los Santos (All Saints Day), from the celebratory (Mexico, Peru, Guatemala) to the somber (Paraguay, Panama), as diverse Indigenous traditions merged with Roman Catholic beliefs during this astronomical midpoint.

Recent history is important when looking at how communities remember their dead. Throughout Central America it is still within living memory that U.S.-supported death squads roamed the cities and countryside killing innocent people and decimating communities. Some left out in the streets as a warning were catechists who taught others to read the Scriptures through the eyes of the poor. In South America, opponents of the military dictatorships were raptured—disappeared—tortured and never seen again. Thus, Día de los Santos can take on a poignancy for communities beset by generations of state-sponsored violence: families shattered, not by disease or old age, but by governments and, recently, street gangs.

On this All Saints Day, I invite white Lutherans to hear the blood of their Latinx siblings crying out to God from the ground.

In the United States, Latinx communities have linked Day of the Dead observances with various societal ills that plague our people. Some have made prayerful processions at the sites of gang violence. In Chicago, a vigil protesting the mass closing of public schools in minority neighborhoods was held in 2017, recognizing that death comes in many forms. Several years ago, the National Museum of Mexican Art, also in Chicago, constructed an altar from empty water bottles, drawing attention to those who die of thirst in the desert seeking to escape poverty and violence.

Our lectionary contains abundant texts touching on death. From Revelation’s joyous multitude to the destruction of the shroud that covers all people in Isaiah to the raising of Lazarus, these readings witness to the sorrow and hope of communities grappling with grief.

To these I want to add one that challenges those of us on this side of privilege to consider how systemic evil brings death. In Genesis 4, God asks Cain, “Where is your brother, Abel?” Cain answers with the perennial question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Can you hear God’s anguished cry? “What have you done? Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground!”

On this All Saints Day, I invite white Lutherans to hear the blood of their Latinx siblings crying out to God from the ground. COVID-19 is taking a disproportionate toll on Black and Latinx communities systematically marginalized from health care systems. Retail “essential workers,” many of them people of color, are still placed at risk to serve those who are able to work from home. In the meantime, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement expels refugees and asylum-seekers and separates families, placing them in overcrowded conditions that help spread disease. In the news we also see police violence against Latinx continuing at an unequal rate to the population, even as the federal government villainizes immigrants and brown-skinned Americans.

Simultaneously, to balance local budgets, some cities cut funding for education and social programs in minority neighborhoods while increasing police spending, a recipe for disaster both now and down the line.

I ask my fellow Christians to reflect on the nature of this country’s and the church’s treatment of Latinx people and other marginalized communities. Listen to the cries of the blood of your siblings throughout church and society. Listen when we tell you that maintaining white supremacist theologies and structures are anti-gospel and lead to death—for brown, Black, Indigenous and white people.

This will make us uncomfortable—as in the other instances when we face death throughout our lives. We may, like Cain, double down and make excuses or simply choose to look the other way. But ask yourself, as God asks us, “What have you done?” And on this All Saints Day, as we witness the dying creation outside our windows, let us have the courage to face our sins and in time emerge to resurrection for all.