How did — and does — the Reformation affect the lives of women? If this relationship was documented on Facebook, the status might be “it’s complicated.”

Argula von Grumbach was a noblewoman and advocate for reform based on her study of the Scriptures. Her first publication was a letter in defense of a university student who had been imprisoned for possessing illegal pamphlets promoting Reformation theology.

The Old Testament tells us that both men and women are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). Paul writes that in Christ distinctions of class and gender no longer matter (Galatians 3:28). Reformer Martin Luther insisted that all Christians, not just some, share by faith in the same spiritual priesthood. Nevertheless, the Reformation had mixed results for women.

At the beginning of the 16th century, women’s life choices were limited. Living as a single, independent woman was simply not acceptable. Most women transitioned from being under the authority of their fathers to that of their husbands and then, if they outlived their spouses, that of their eldest son.

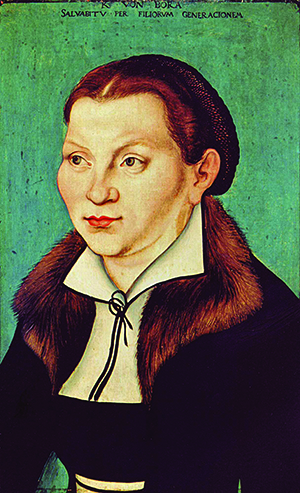

Some women joined convents, but this was often their parents’ choice rather than their own. For example, 12th-century mystic Hildegard of Bingen was the 10th child in her family and her well-to-do parents gave her to the convent as a tithe (10 percent of their assets given to God). Katharina von Bora, Luther’s wife, was sent to a convent at age 5 when her father remarried after her mother’s death.

During the Middle Ages the celibate life of a nun, monk or priest was seen as a “higher calling” than the married life of ordinary people. The reformers rejected this idea. Instead, they praised both marriage and parenthood as worthy callings for all Christians.

LUCAS CRANACH THE ELDER WORKSHOP, 1529.

Scholars today describe Katharina von Bora, Martin Luther’s wife, as a housewife and the manager of a midsized business, feeding family, student boarders and frequent guests by purchasing land, raising crops and livestock, and handling all the household finances.

For centuries the church had taught that the primary purposes of marriage were reproduction and providing an acceptable outlet for sexual desire. Reformers like Luther and John Calvin promoted a new understanding of marriage as loving, faithful companionship.The good news in this is that the Reformation recognized and celebrated the value of women’s status as wives and mothers. At the same time, by closing convents the reformers eliminated the option that had provided some women the opportunity to receive an education, exercise leadership and live in a supportive community of other women.

Nevertheless, the reformers promoted education for all boys and girls, which was astonishing for the time. Education had been available only for boys of higher social or economic status. The Lutheran emphasis on reading the Scriptures for oneself sparked an emphasis on literacy for everyone. Luther encouraged communities to establish and support schools and urged parents to send their children — boys and girls — to school rather than keep them at home to work.

But education for girls was much less extensive than for boys. Girls attended school fewer hours a day than boys and for fewer years,with skills geared toward reading the Bible, managing a household and teaching the faith to their children.

In short, we can see some progress for women in the Reformation of the 16th century, but not as much as we might like. Yet the vision for an educated laity did benefit women. By the second generation of the Reformation, more than 90 percent of pastors’ wives were literate.

Today we could say things are still complicated for women in the U.S. and around the world.

The ELCA’s International Women Leaders seminars, titled “Women at the Crossroads of the Reformation,” were funded by gifts to Always Being Made New: The Campaign for The ELCA. Forty-six women from the ELCA’s companion churches have participated.

Depending on which statistics you accept, women in the U.S. still earn only two-thirds to three-fourths as much as men for the same work. According to the 2014 Global Gender Gap Report of the Geneva-based World Economic Forum, the U.S. ranks 65th of 142 countries in terms of wage equality. The same report found that girls and women have equal access to education in 25 of 142 countries.

Seventy-seven percent of the church bodies in the Lutheran World Federation ordain women. But women in those countries report that female pastors often don’t have equal access to decision-making roles or to higher education opportunities beyond a theological diploma.

Since October 2014, I’ve led a series of ELCA seminars in Wittenberg, Germany, for women from Lutheran churches in the “global south” (Africa, Central and Latin America, and most of Asia) andthe former Eastern bloc. The theme of the seminars is “The Reformation and the Empowerment of Women.”

Most of the participants, pastors and laywomen, report gender-based discrimination not only in their countries but also in their churches. Lindie Kanyekanye, a pastor in Zimbabwe, said “a real woman gives birth to boys.” If she doesn’t, the man is likely to take another wife.

PHOTO BY ALEPH

German Chancellor Angela Merkel was raised as a Lutheran pastor’s daughter in the former East Germany. Merkel has been ranked by Forbes as one of the most powerful women in the world for nine of the last 10 years.

The Malagasy participants agreed: in Madagascar, sons are valued because of their own worth; daughters are valued because of the bride-price they will generate for the family. Nima David from India knows a man who says he has no children — in fact, he has five daughters, but to him theydon’t count.

Strong women from the past

How can learning about the Reformation make a difference? It’s useful to consider not only the impact of the Reformation on women’s lives but also the impact of women on the Reformation. Reflecting on these past leaders can help us draw information and inspiration for our lives today. (See page 14.)

We can’t pretend that Luther shared our views about the equality of men and women. His writings show some ambivalence. In his commentaries on Genesis, for example, Luther sometimes describes the subordination of women to men as part of God’s created order. At other times he identifies subordination as the result of sin.

Julinda Sipayung is a pastor from Indonesia who attended the ELCA’s International Women Leaders seminars.

Nevertheless, for his time Luther was remarkably progressive. While he married for practical reasons, he came to love and respect his wife, Katharina, very much. Also known as Katie, she was one of the nuns Luther had helped escape from their convent after they wrote to him asking for assistance.

Scholars today describe Katie not just as a housewife but as the manager of a midsized business. To feed a household consisting of family, student boarders and frequent guests, she purchased land, raised crops and livestock, made beer and wine, and handled all the household finances.

The seminar participants are inspired by Katie’s strength and accomplishments, but they don’t see her as unique. Julinda Sipayung, a pastor from Indonesia, said, “This is just like the women in our country. When the men don’t make enough money to provide for the family, the women go out to work too.”

Paulina Hlawiczka is pastor of two congregations of the Lutheran Church in Great Britain, but works for reform in her home country, Poland, where women can’t be ordained.

Darwita Purba, a pastor from India, agreed, as do participants from Tanzania and Gambia. Despite traditional beliefs that women belong in the home rather than the workplace, these women’s experiences confirm the reality that, in practice, the line between domestic and economic responsibilities is often blurred.

Katie was such a good provider that Luther chose to leave everything to her in his will, a move that was unheard of at a time when it was assumed that a widow needed a guardian to act on her behalf. While the authorities, including Luther’s friends, refused to honor his wishes, Luther’s desire to make his wife his heir is remarkable.

We can also take inspiration from Katharina Schütz Zell, another 16th-century woman. Even as a child she believed a woman could live a holy Christian life without joining a convent. At first Katharina opted to live as a single woman in her family home. Later she chose to marry her pastor, Matthias Zell, who was one of the first preachers of reform in Strasbourg, a city on the border between Germany and France.

MICHAEL ANGELO

Nobel laureate and peace activist Leymah Gbowee is a member of the Lutheran Church in Liberia and participated in the ELCA’s International Leaders program, completing a master’s degree in 2007.

But Schütz Zell wasn’t the typical pastor’s wife since much of her ministry took place outside the home. She was incredibly active in social ministry: visiting the sick and imprisoned and arranging for housing and support for hundreds of refugees. For her this wasn’t just a personal expression of her faith but a public ministry of the church. Although a laywoman, her husband referred to her as his assistant minister.

Schütz Zell also wrote extensively, even corresponding with Luther. One of her earliest published writings was a defense of the marriage of pastors. Zell’s marriage at a time when priests were required to remain celibate had prompted gossip and threatened to undermine the credibility of his preaching. Schütz Zell insisted that she wasn’t writing as a wife in defense of her husband but as a Christian in defense of another Christian. All Christians, including women, had the responsibility to stand up for the truth and defend their neighbors from slander. Keeping silence in the face of injustice, she wrote, wasn’t acceptable.

By today’s standards, Schütz Zell’s theology is classified as Reformed rather than Lutheran, but she resisted such labels. To her mind, all Protestants were working together for reform. A shared commitment to the gospel and the authority of the Scriptures was more important to her than doctrinal differences. She even preached at the funeral of two women whom no Christian pastor in Strasbourg would bury because they supported believers’ baptism rather than infant baptism.

Fast forward to 2011, when the magazine of the Women of the ELCA changed its name from Lutheran Woman Today to Gather. Why? The organization’s leadership learned that other Christian women were also reading and benefiting from the magazine, especially those in churches that are full communion partners of the ELCA and don’t have women’s magazines of their own. Gather, together with its tagline “For faith and action,” would have pleased Schütz Zell.

But pastors’ wives weren’t the only women who contributed to the Reformation. Argula von Grumbach was a strong advocate for reform based on her study of the Scriptures. Astonishingly for the time, her parents had given von Grumbach her own copy of the Bible when she was 10. Her first publication was a letter in defense of a university student who had been imprisoned for possessing illegal pamphlets promoting Reformation theology.

A woman from a noble family, von Grumbach attended several imperial assemblies at which the cause of reformation was discussed. She was a prominent enough figure that when Luther mentioned her in letters to other reformers, he used only her first name. Unlike the two Katharinas, von Grumbach didn’t have a supportive husband. In fact, he lost his position as a government official because he couldn’t keep his wife quiet. But his disapproval of her activities didn’t stop her.

We can praise women like these as exceptional figures, but none of them thought of herself as heroic. Each was simply living out her faith as she felt called to do, within her own circumstances.

Strong leaders in the present

How does this legacy of strong women of the Reformation live itself out today? Faith continues to empower women leaders around the world.

Paulina Hlawiczka, a pastor who serves two congregations of the Lutheran Church in Great Britain, said in her native Poland, Katie Luther is used as an example against women’s ordination. “Why don’t you marry a pastor?” she was told. Convinced that God was calling her to be a pastor rather than to marry one, Hlawiczka needed to leave Poland to be ordained. Today she prays and works for change in her home country and church.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whom Forbes has ranked the most powerful woman in the world for nine of the last 10 years, is also a Lutheran. She was raised as a pastor’s daughter in the former East Germany, where being a Christian typically had educational and political disadvantages. As a teen she chose to be confirmed despite the social pressure in East Germany to go through the alternative communist “youth dedication” rite instead.

Merkel doesn’t speak much about her faith in public, but it clearly motivates her. In response to questions from a theology student on a blog in November 2012, she wrote: “I am a member of the Evangelical Church. I believe in God, and religion is also my constant companion and has been for the whole of my life.”

Merkel described belief as a framework for her life and how she sees the world. “We as Christians should above all not be afraid of standing up for our beliefs,” she said.

In a very different part of the world, Liberian Lutheran Leymah Gbowee was one of three women awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 “for their nonviolent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.”

In 2003, Gbowee organized a group of Christian women — and then built a coalition with Muslim women — to protest against Liberia’s corrupt government and end its long civil war. Gbowee’s faith motivated her courageous action, she told the Women of the ELCA Triennial Convention in 2011, and that same faith should motivate all of us to rise up, get out of our comfort zones and work for justice in God’s world. “The God we serve is not a God of halfway [but] a God of wholeness,” she said, and “[God] who called you will equip you.”

Back in Wittenberg, Kanyekanye, the pastor from Zimbabwe, echoed this sentiment: “We have a voice that is more powerful than we can imagine.”

Some of the participants in the women’s seminars were not raised Lutheran or even Christian. They became Lutheran in response to the good news that they encountered in word and action through the global Lutheran church. These women are living testimony that the gospel continues to create faith and transform lives even 500 years after the beginning of the Reformation.

The powerful message of God’s grace through faith in Jesus Christ is not “old news.” It is a life-giving treasure that we have received and are called to share. As ELCA Presiding Bishop Elizabeth A. Eaton reminds us: “We are church, we are Lutheran, we are church together, and we are church for the sake of the world.”

That “we” is all of us — women and men, clergy and lay, young and old. Maybe it’s not so complicated after all.

Katie’s Fund

Women of the ELCA chose to name its endowment Katie’s Fund. In the spirit of Katharina (Katie) von Bora Luther, theorganization receives and manages money to support ministry in three areas: leadership development, global connections and living theology. Katie’s Fund is now more than $1 million.Learn more at www.welca.org/katiesfund.