Editor’s note: We asked synod bishops: “What book most radically changed your thinking on matters of faith, and why?” Here’s how five answered.

“Ministry among the people”

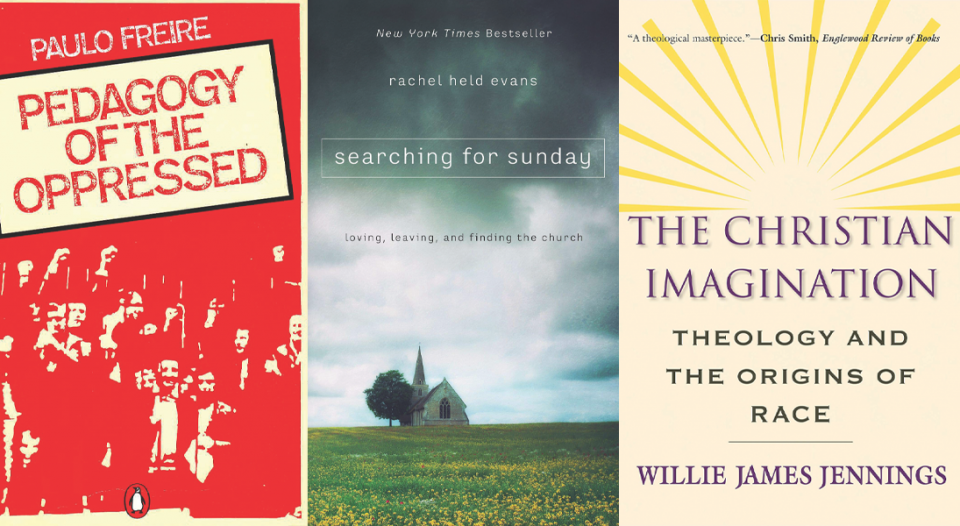

Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Penguin, 2017) forever changed the way I think about my faith, the way I taught confirmation and the way I preached sermons and connected them to daily life and congregational ministry. Freire teaches a process of unmasking the assumptions that cause people to oppress and/or tolerate their own oppression. He models a transformational ministry among the people based on an action-reflection-action-reflection model of observing, codifying, learning and living with the belief that the gospel has something to say about how we live and engage in the world. He writes of more than “pie in the sky when you die.”

Freire himself was far from perfect, yet his book helped me appreciate more fully Jesus’ ministry among the people. It helped me move beyond a chaplaincy model for ministry and beyond religion as an opiate.

—Michael Rinehart, bishop of the Texas-Louisiana Gulf Coast Synod

Revealing God anew

One book that changed my way of thinking about faith is Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving, and Finding the Church (Thomas Nelson, 2015) by Rachel Held Evans. Maybe it’s because I grew up in an evangelical background, so I can relate to her love of church and Jesus in the lived experience of the evangelical. As a young person, Held Evans truly loves God and wants to serve God. She’s convinced there is a way to be a super-shiny Christian, and all will be well. And then life happens. There are heartaches in her personal life, and more shockingly, there are disappointments with her church and pastors. She relocates to a liturgical church and is delighted and surprised to see the holy sacraments as vital, life-changing experiences.

This book made my heart sing as I understood in fresh ways how God is revealed to us in the waters of baptism and in communion. Sure, we talk about this a lot in the Lutheran world, and we should, but it was great to read a book filled with such unabashed joy and unapologetic love for God but written by someone not born into this type of Christianity.

—Brenda Bos, bishop of the Southwest California Synod

Inspiration for a life of learning

My desire is to focus narrowly on the question as asked. The question is not “What book has been most important, or had the best ideas, or struck me as most profound or most useful?” and so on. The question is, “What one book radically changed your thinking when it comes to matters of faith? Why?” The book is C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity (HarperOne, 2015). Why? During my college years, I had many questions about God, faith, religion and church. My thinking on these things was initially geared to “What is the right answer?” Mere Christianity got me to think about the easily overlooked question “Am I asking the right questions?”

First published in the 1940s, Mere Christianity was already “dated” when I first read it in the 1970s. But Lewis’ straightforward, dogged pursuit of issue after issue inspired my future deep dives into theology, hermeneutics and epistemology. For example, whether I agreed, agreed in part or disagreed with the following statement from his fifth chapter, I could not ignore it: “We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning, then to go forward does not get you any nearer.” Wrestling with Lewis’ Mere Christianity sparked my lifelong pursuit and love of learning.

—John Roth, bishop of the Central/Southern Illinois Synod

“Healing requires renewed theology”

I didn’t realize at the time what a gift I received from Ronald E. Peters, a Presbyterian pastor and professor, when he encouraged me, a new board member of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, to read The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (Yale University Press, 2010) by Willie James Jennings.

Before finishing the first page, I wrote in the margin: “This is my story too.” What resonated so strongly and so joyfully with my experience was the author’s reflection on his earliest faith formation: “The stories of Jesus and Israel were so tightly woven into the stories my parents told of themselves … that it took me years to separate the biblical figures from extended family members.”

But by page 9, I realized that Jennings intended to reveal our default location within “the story of modern Christianity’s diseased social imagination.” This was a more sobering experience of recognition, but it was also the greater gift.

Through four compelling narratives—“Zurara’s Tears,” “Acosta’s Laugh,” “Colenso’s Heart” and “Equiano’s Words”—Jennings works as a film director would, telling the painfully personal stories of people facing “newfound worlds” between 1444 and 1854, as European exploration and pursuit of empire dislocated African and Native American people from their lands of identity. Theological reflections on literacy and belonging carry the book toward its conclusion.

I came away from the book with a conviction that our world’s healing requires renewed theology as generous as Jesus’ self-giving and as humble as the soil to which we all belong.

—Kurt Kusserow, bishop of the Southwestern Pennsylvania Synod

A field guide to prayer

As a young pastor serving my first parish, I struggled with helping the folks God called me to serve to grow in their devotion and discipleship. Then I started a small prayer group, and we devoted ourselves to simple prayer practices. As we grew in our practice, we sought to go deeper but were uncertain where to go.

A local United Methodist pastor introduced me to Richard J. Foster’s book Prayer: Finding the Heart’s True Home (SanFran, 2002). This book served as a field guide to our prayer group, and we learned to explore and practice a life of prayer that brought intimacy with God, personal spiritual transformation and a desire to love and serve our neighbors. It transformed our small group, which in turn renewed our entire parish. Foster taught us that prayer is foundational to building a life with God, one another and the community.

As I recount my days in parish ministry, I remember Foster’s words: “Coming to prayer is like coming home. Nothing feels more right, more like what we are created to be and to do.”

—Daniel G. Beaudoin, bishop of the Northwestern Ohio Synod