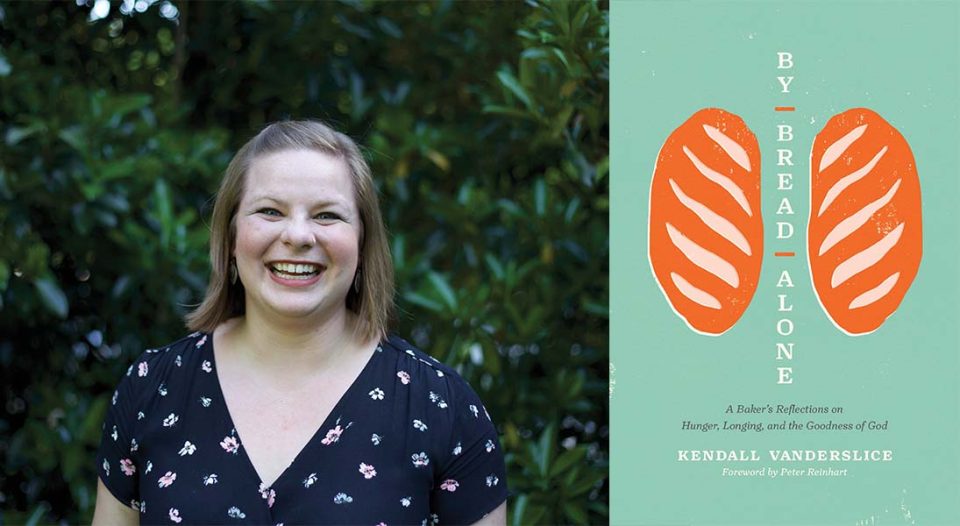

Kendall Vanderslice is a professional baker, the founder of the educational nonprofit the Edible Theology Project and a 2018 James Beard Foundation national scholar. Her new book By Bread Alone: A Baker’s Reflections on Hunger, Longing, and the Goodness of God (Tyndale Momentum, 2023) weaves together her personal story and the theology around bread and sharing meals.

Living Lutheran connected with Vanderslice about By Bread Alone, her organization and some of the personal stories in her book.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about your book?

Vanderslice: I like to say that this book is a theology of bread as told through my story. Bread is present all throughout the narrative of Scripture and also throughout Christian practice, but in general we have a very underdeveloped theological understanding of bread.

While working as a professional baker, I became fascinated with the spiritual parallels woven into the process of baking bread. My love of and knowledge of bread shaped the ways I saw bread at play in the Bible. I then went to Duke Divinity [School in Durham, N.C.], where I wrote a thesis on a theology of bread. But at the core what I found was that bread is God’s way of being present with us in a tangible form, a kind of communion that cannot be captured fully in words.

This made writing about bread an ironic task. In the end I could only get at this theological understanding of bread through narrative, through poetry and through recipe—by sharing the ways that God has transformed me through the baking of bread, in community, and encouraging others to seek God in a similar way.

Your relationship with food hasn’t always been smooth. Could you share with us some of what you’ve learned through those challenges?

Growing up as a child of the ’90s, and also being trained in classical ballet, I was constantly taught to scrutinize my body. I loved food, but my family was always oscillating from diet to diet and, even with our strict eating regimens, I was much larger than my peers. I spent my middle school and high school years in the throes of disordered eating. In college I was diagnosed with PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome]—a hormonal disorder affecting about 1 in 5 women—and I was encouraged to try and manage it through my diet. This created the perfect excuse to further mask my disordered eating until finally I couldn’t take it anymore.

It was the bread offered to me week after week in communion that began to heal me and my relationship to bread, to my own body and to the church. Honoring God with my body looked like allowing myself to find joy in food, a good gift from God, and its ability to draw us together as the body of Christ.

Bread is God’s way of being present with us in a tangible form.

When we look at the story of Genesis 1-3, we see two things holding true at the same time: food is a delightful gift from God, and also, through food we experience the brokenness of creation. Humans were created with two basic needs: the need to eat and the need to live in community. Shared meals address both of the needs at the same time.

From the very beginning of creation, caring for and delighting in the gifts of God took the form of eating. But also it was through eating that we see the breakdown of creation, which has ramifications on the very production of our food. “The ground will sprout forth thistles and thorns. By the sweat of your brow, you will eat your bread,” [to paraphrase] Genesis 3:18-19. We all experience both the goodness and the brokenness of creation in relationship to food, even if the ways we experience pain differs—be it allergies, eating disorders, food insecurity or even being made fun of for the foods of our culture.

But it’s also through a meal that Jesus marks God’s commitment to the restoration of creation, which means that through food we can also experience healing. Learning to treat food as a gift from God, meant for my joy, my healing and for the building of community, is what ultimately helped me to overcome my history of disordered eating.

One of the book’s themes is your own singleness as a woman in the church. Could you share some of your thoughts on singleness and how to best support single friends and parishioners?

Everyone’s experience of singleness is very different. What is hard and what is fun about it changes from person to person and even from season to season. But what’s constant among those who are single and also those who are not is that we were created with the need to share our lives with others. The only thing called “not good” in Genesis 1 and 2 is a human being alone.

Both church culture and the broader culture tend to emphasize that our need for companionship will ultimately be met through a romantic partner. But for an increasing number of people, that’s simply not true. And theologically I don’t think it’s an adequate answer either. I’ve talked to enough young parents and empty-nesters alike to know that loneliness plagues us all.

Ultimately we all need community—people we share the ups and downs, the rhythms of our life with. When we recognize that that is our primary need, it frees us to see how the gifts and the limitations of our own life can counterbalance the gifts and limitations of friends who are in a different season.

Humans were created with two basic needs: the need to eat and the need to live in community.

My flexibility means that I can join a friend at the last minute when she and her kids are going to the playground across from my house. I can sit on the sidelines at soccer games with friends, cheering on their kids, and I can provide a clean, quiet house when they need some space and adult conversation. My ability to recognize the gifts of my singleness, and also my ability to articulate the ways it is hard, opens me up to hearing about both the gifts and the difficulties of my friends’ lives that look so different from mine.

My best advice is to listen closely—when your single friends or parishioners express what is hard, believe them. Create space for that pain to be present. And when they express what they enjoy about singleness, don’t tell them how lucky they are. … They are aware of the cost and that joy is hard-won. Most of all, include them in the rhythms of your life, even the things you might believe are boring or mundane. Friday night pizza dinner, Saturday morning swim lessons, a Memorial Day cookout. It’s a gift to you all.

What makes food and theology a good pairing?

We could have been created with root systems that could draw up energy out of the ground, but instead we were given taste buds and tables. Our basic need for nutrition is met in a manner that not only tastes delicious but that draws us into community with others as well.

I like to say that the gospel is a story of meals: a meal that brought destruction and a meal that brings new life. Christian worship is also built around a meal—the communion meal that we share each week. Something really powerful happens at the table simply because our creative God chose to make it this way.

At the Edible Theology Project, our goal is to help people see the ways our food shapes our understanding of home, of family, of the places we live and how all of this connects to the meal that stands as the cornerstone of Christian worship. We do this primarily through our two [curricula], Bake With the Bible and Worship at the Table, which explore the roles of bread and of meals more broadly in both the Bible and in Christian history.

What are your hopes for your readers?

I hope this book serves as a gentle invitation to see the goodness of God in simple, tangible ways. For those who have a complicated relationship to God, to the church or to their body, I want this book to be a deep breath of fresh air. After reading it, I hope you never participate in communion in quite the same way again.