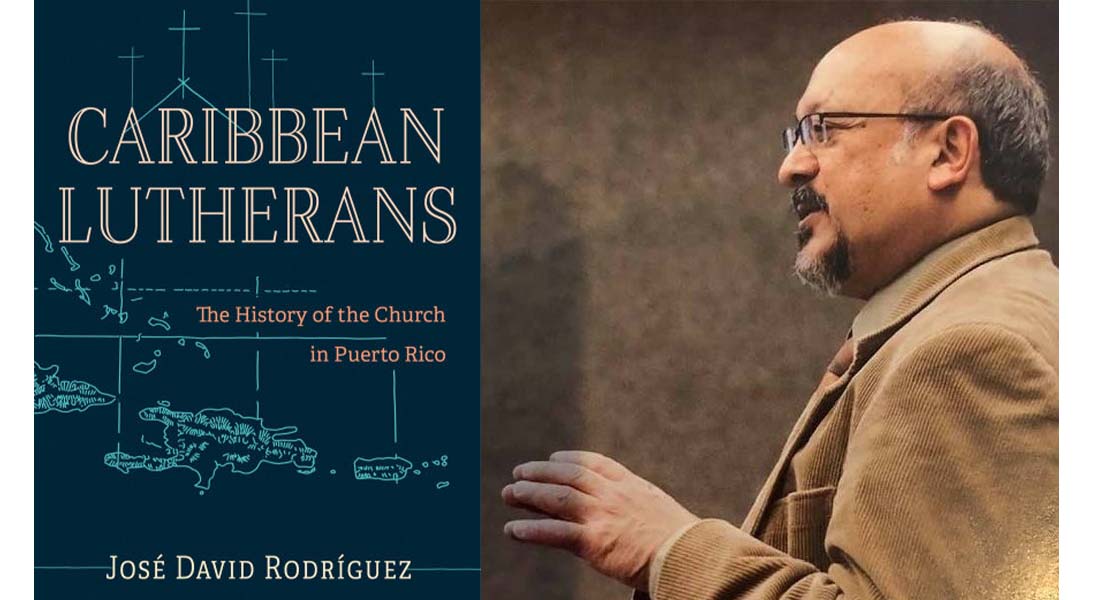

For José David Rodríguez, what began as a doctoral dissertation is now the first academic history of the Lutheran church by a Puerto Rican.

Rodríguez’s new book, Caribbean Lutherans: The History of the Church in Puerto Rico (Fortress Press, 2024), first took shape through a Ph.D. program in the Department of History at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica. An ELCA pastor and professor, Rodríguez had long hoped to put together a history of how the Lutheran mission in Puerto Rico began and evolved. But when he visited the Archivo General de Puerto Rico (General Archive of Puerto Rico) to begin his research, he found no information.

His project became one of recovering history, of relying on oral tradition, historical archaeology, social history and women’s history to tell the story of the Lutheran church in Puerto Rico from a Caribbeanist perspective.

He brings to the book both academic expertise and personal experience, taking an accessible approach and adding a postcolonial perspective to this history. Living Lutheran spoke about the book with Rodríguez, who is the Augustana Heritage Professor Emeritus of Global Mission and World Christianity and professor emeritus of systematic theology at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about Caribbean Lutherans?

Rodríguez: It’s the first historical, systematic approach to the history of the Lutheran mission in Puerto Rico. It incorporates a serious, professional historical approach along with—since I’m a systematic theologian as well—excerpts where I deal with the topic of the Lutheran theological background of the missionaries and the place where the candidates for the ministry in Puerto Rico did their university and seminary formation. There are a lot of interesting things about the type of Lutheran missionary approach [covered in the book] and the theology behind that approach.

In fact, one of the things that I say in the book is that in Puerto Rico, the Lutheran church changed its approach to mission. For example, the Danish church in the Virgin Islands that started in the 17th century—and other approaches to mission up to the 19th century in Puerto Rico—their approach was that they would develop a Lutheran colony. All the Lutheran [worship] services were just for those who came together from Europe in Puerto Rico. There was a change in mission because, although the first Lutheran church that was established Jan. 1, 1900, [held services in] English, three months after that they established the first Lutheran church in Spanish. That didn’t happen in other Lutheran missionary enterprises in the Caribbean, or in the United States, for that matter.

So in a way, what happened in Puerto Rico was a threshold of how to engage in different approaches to Lutheran missionary work. And I think people will appreciate how the Lutheran work in Puerto Rico [dealt with] many important issues that are still so relevant for the church today.

You intentionally took what you call a decolonized approach to telling this history. What did that involve?

The most prominent works or studies that were published about the presence of Protestantism in Puerto Rico from 1898 to 1930 [employed] an imperialist historiographical approach. What they do is they project the history of an empire, either Germany or France, into the Caribbean. A decolonized approach takes much more seriously what’s happening in the Caribbean and takes the approach of starting from the Caribbean and then dealing with the research done by other historians in other parts of the world. My book is the first one that deals with the Lutheran mission in Puerto Rico from a Caribbeanist approach.

The other thing that characterizes my approach is dealing with the history. It’s a difficult task when you’re dealing with an ancient period. One of the problems that the Caribbean Synod had was that during the 1960s [it] had used a church to gather all the historical data. And that church burned down [and lost much of its archives]. So it was so difficult to gather the data of the history. I went to the archives of the church and there were important contributions, but … it’s not complete. So the issue was, how do you complete the history? Where do you find the data that is not collected officially? Well, the postcolonial and decolonial approach helps in doing that.

What you find in my book is stories that convey the experiences that the official documents don’t have.

The postcolonial and decolonial approach finds, in nonofficial documents and means of communication, information that was shared at that time. For example, I use music, because one of the interesting things about particularly popular music is that it is used at times as a means to convey history. And art is used for that purpose as well. From a more popular perspective, one of the interesting things I used was a book of poems from a pastor by the name of Francisco Molina, who was a literary artist in Puerto Rico. In his poems he [references] some historical happenings of the Lutheran experience in the island.

So this approach allows me to fill some gaps that were in the official documents. First of all, if they had it, these documents got burned and there is no way to recover them. But these alternative means of recording history are interesting. A social anthropologist at Yale University, James C. Scott, calls them “the weapons of the weak.” Because these are the ways that the underrepresented groups of society, who lacked the power of the dominant sectors of society, communicate: humor, art, music, gossip (laughs) and the like. What you find in my book is stories that convey the experiences that the official documents don’t have.

How did you ultimately decide to write the book?

When the fire took place, I was a pastor already in the Caribbean Synod and my uncle was the bishop—or, at that time, president. So I learned about that, and it really hit me hard because I was part of the Lutheran church. It was a tragedy.

Records had also already been collected in the United States by the United Lutheran Church in America and later, in 1962, the Lutheran Church in America. The problem with the records is that they are not complete. There are some voids—lagunas—and the issue is, how do you maybe fill out those empty spaces?

What drove me to do it was not just this understanding that the records were burned but something still more important. When I began as a professor at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, the faculty gathered in a guild of Lutheran scholars. And the first time I went to that organization of the Lutheran scholars, I heard people from the German and European Lutheran tradition speak about the studies that have been made about Lutheranism that had already [been] published. When it got to my turn, I couldn’t mention any study. It was just oral history. And that really triggered a [feeling of being] so uncomfortable. Because I knew that we had a history to share, but the problem was that there wasn’t any serious study done about that history. And when I finally retired, I said, well, if no one has done it, I’m going to go do it.

I’m really excited that I’m working with a pastor, Enrique Mercado Cruz, to complete the history [of events after those covered in my book], up to the time when, in 1988, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America was established. I think this research is going to make an important impact in the way that the ELCA and the Lutheran church in Europe look at the contribution of Lutheranism in the Americas.