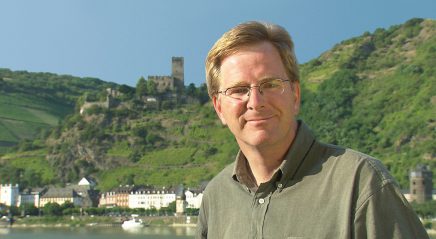

As a travel guide, Rick Steves knew his business was contributing to climate change. Last year, the host of the popular PBS series Rick Steves’ Europe—and a member of Trinity Lutheran Church, Lynwood, Wash.—announced a significant effort to do something about it.

In 2019, Rick Steves’ Europe launched its Climate Smart Commitment initiative, imposing upon itself an annual $1 million “carbon tax.” The company invests the funds each year in a portfolio of 11 nonprofit organizations working to fight climate change, including ELCA World Hunger.

“Climate change is real,” Steves said in a statement. “It hurts poor people in poor countries the hardest. And as travelers, we need to be honest: We’re contributing to it.”

The organization’s $100,000 grant to World Hunger continues to bolster the ELCA’s work with global partners, supporting smallholder farms and their communities. With the funding, the ELCA has been able to introduce more sustainable farming practices, improve water availability, provide carbon-efficient cookstoves, reduce deforestation and increase local security in more than 60 countries.

“The Rick Steves Climate Smart grant has enabled us to continue our work with companions who are engaged in projects related to climate change,” said Rebecca Duerst, ELCA director for diakonia, “especially work with communities that bear the burden of the impact of climate change globally, to strengthen resilience, implement solutions to adapt, and work to mitigate its effects.”

“Climate change hurts poor people in poor countries the hardest” said Steves. “And as travelers, we need to be honest: We’re contributing to it.”

It is widely reported that almost 80% of the world’s food is produced on small farms, but about half of the world’s 800 million undernourished people live on such farms. As the impact of climate change increases, the world’s food supply will become more insecure and hunger in many regions will increase.

World Hunger addresses these changes through long-standing relationships with companion churches and other partner organizations that are embedded within their communities—many of which, Duerst said, are in rural areas where families rely on subsistence farming for food and income.

In Senegal, funds from the grant are being used for a dairy center project that enables cattle herders, especially women, to increase milk production. In India, modernized agricultural techniques, disaster preparedness training and irrigation improvements are strengthening communities’ resiliency.

The grant is similarly supporting innovative practices in rural Vietnam for alternative sources of fuel, in Cambodia for drip irrigation and crop diversification, and in Colombia for coffee production with less water and no chemicals.

While World Hunger’s partnerships are long-established, these new and creative approaches continue to help guarantee food and income for families in the context of climate change.