As the coronavirus pandemic has swept the globe, it has brought pain and loss, disrupted lives and pushed many to a breaking point. But this health crisis has created something else too—a call to service, a spirit of helping others, a renewed appreciation for what truly matters.

Through their professional roles and volunteer endeavors, Lutherans have felt this call to provide comfort, assistance and the promise of God’s love to their fellow human. Whether through front-line work with patients, comforting grieving families, making masks, or donating time and supplies, Lutherans are stepping up to help others weather this storm. Here are a few of their stories.

Answering the call

Tammy Schacher never imagined she’d be working on the front line of a global pandemic. As the assistant to Jon Anderson, bishop of the Southwestern Minnesota Synod, Schacher stays busy helping the office run smoothly. But after her day job ends, she puts on her second hat as a volunteer EMT and ambulance director in rural Minnesota.

In many rural areas, hospitals and fire departments rely on volunteers to provide service to outlying communities. Schacher said she signed up for EMT training after realizing there was a shortage of volunteers in her area.

“Ten years ago, I was really sick one night, and my husband was on the fire department, and I’d hear them calling over the radio,” she said. “They had to page twice for an ambulance because they didn’t have enough people. I knew there was a need, and I felt like I needed to help.”

Schacher devotes 10 hours per week to her role as an ambulance director, fielding calls and making sure her staff is aware of ever-changing COVID-19 protocols. On top of that, she answers as many calls as possible as an EMT.

“Bishop Jon has always been very supportive,” she said of juggling her volunteer work with her synod job. “Last week we were in the middle of a Teams call, and the tones dropped and he said, ‘Go.’ Bishop Jon says I always run to the fire—that’s why I’m the synod assembly manager, and that’s why I do this.”

While Schacher said an EMT’s role is often challenging due to the severity of most calls, the job has gotten significantly more difficult during the pandemic.

“The hard part about this COVID period for me has been having to defend these deaths and having to defend the work that we do,” she said. “It’s not about being a hero—none of us do this for that—but having to defend putting your mask on. If you don’t believe this is a real thing, why don’t you get in the ambulance with me? It’s been very hard emotionally, and I’m tired.”

Despite the challenges, Schacher still loves this service because it allows her to be a tool of God to provide comfort to those who need it most. “Sometimes you put yourself aside and let God do his work,” she said. “You just sit and be silent and pray, and it’s amazing what you can do in that time and space.”

Helping families say goodbye

Few cities have been harder hit by COVID-19 than New York City. Chris Kasler, a member of Lutheran Church of the Good Shepherd in Brooklyn, knows the sum of that human toll better than most. A funeral director at Sherman’s Flatbush Memorial Chapel, he has buried hundreds of COVID-19 victims.

“Average funeral homes do around 200 funerals a year; we’re at about 1,400 this year,” he estimated in late December. “We had 402 COVID funerals in six weeks. I never thought in my wildest dreams I’d see anything like this.”

Kasler is no stranger to death. He grew up in the funeral business, the son and grandson of funeral directors. When his family sold their business, he went to work at Sherman’s, the oldest Jewish funeral home in Brooklyn.

During the spring 2020 COVID-19 surge, Kasler said the funeral home was so inundated with bodies that they were forced to temporarily store them in wooden boxes on the pews in the chapel, turning the air conditioning temperature as low as possible.

The staff was completely overwhelmed, not only with preparing bodies for burial or cremation but also with trying to support the bereaved families.

“You’re dealing with people during an extremely emotional time, and a lot of the deaths are unexpected,” Kasler said. “A lot of them aren’t people who are sick. They’re old, but people expect to be with their parents for another 10 years, and then comes the virus and that’s all gone.”

For Kasler, being able to help families through the difficult process of saying goodbye feels like an extension of his faith, a way to bring God’s peace and comfort to those in need. But during the pandemic, he has had to lean on that faith himself, to help him get through an unprecedented time of grief.

“It’s a ministry that I think is often forgotten,” he said. “I know that I’ve made a difficult time easier for people, but this is one time that it was harder on me personally because I couldn’t make it easier for people. My faith goes much, much deeper than my skin, which is probably why I’m still doing what I do. It’s rough.”

Meeting the need

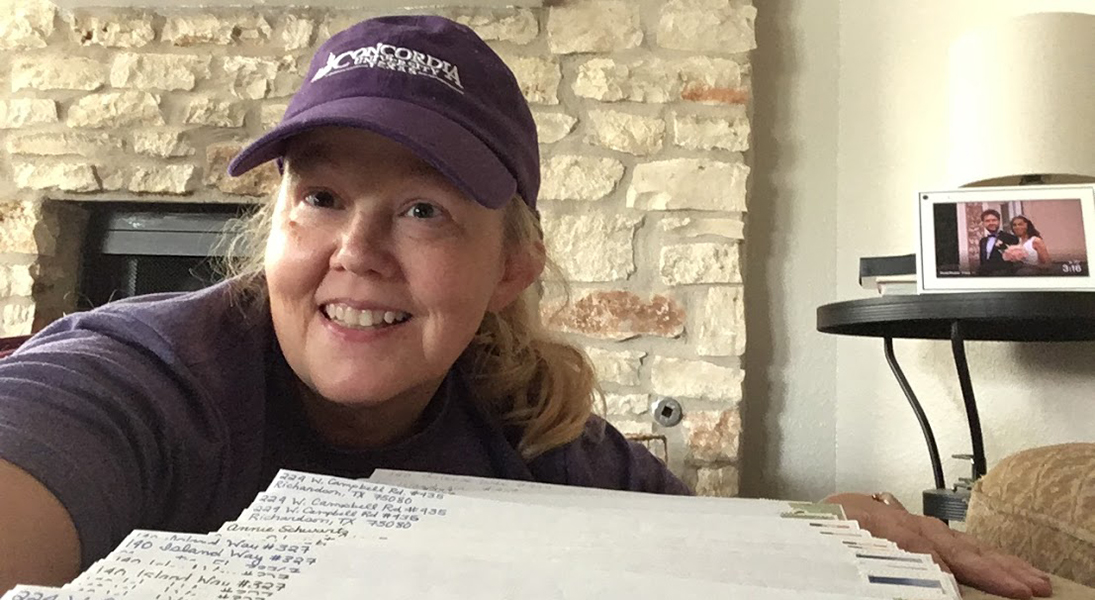

Like so many, Ann Schwartz sat inside her home last spring, wondering how she could help those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. She was on sabbatical from her job as a sociologist, so Schwartz had time on her hands and wanted to use it for good.

So she thought back to her 4-H days and brushed off her sewing machine to make masks for Lutheran World Relief’s “75,000 Face Mask Challenge.” But after sewing masks for the effort, she wanted to do more.

Schwartz got involved in outreach work at her congregation (Grace Lutheran in Round Rock, Texas), delivered meals to retirement community residents and donated supplies to an emergency shelter for children.

Still, Schwartz wanted to do more. Relying on her training as a sociologist, she got involved with several organizations that were working in Austin to do online monitoring of the virtual eviction courts. The work they did helped convince city officials to halt evictions during the pandemic, and Schwartz hopes it will have a lasting impact on how evictions are handled.

“We recognize it more when more people are impacted, but there are people affected by eviction all the time,” she said. “Because it’s happening on a larger scale right now, and the way we look at the pandemic, it’s causing people to see the issue in a different way.”

Schwartz sees the work she’s done as living proof of the power of “God’s work. Our hands.”

“It’s an outgrowth of my faith,” she said. “There are different ways we can love and serve our neighbor, and that can happen on a very personal, individual level. But we are also called to look at how we can impact systems, and because I’m a sociologist, that is a lens I use when thinking about the world.”

Bringing hope

Spring 2020 was one of the most difficult seasons of Charleen Tachibana’s medical career. As chief nursing officer and senior vice president for quality and safety at Virginia Mason Health System, Tachibana worked at the epicenter of the burgeoning pandemic, just miles from Life Care Center of Kirkland, Wash., the location of the first COVID-19 outbreak in the United States.

“That nursing home is a block from our church (Holy Spirit Lutheran)—it really was close, and there were a number of our members there,” Tachibana said of the nursing facility that recorded 46 deaths among residents, staff and visitors.

That outbreak was just the beginning. As the pandemic intensified, Tachibana and her team worked around the clock, logging 13- to 15-hour shifts some days, to treat those affected by the virus.

“We didn’t know what we were dealing with,” she said. “There were no standards of care or protocols developed. There was a lot of coordination across the county and with the state, trying to understand and put standards of care together very rapidly. Our intent was to keep our workforce safe and save as many lives as we could.”

During those difficult times, Tachibana—a graduate of ELCA-affiliated Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, Wash.—leaned heavily on her faith to stay focused and overcome the previously unimaginable challenges of working to save lives during a pandemic.

“You’re just being called to a different reason for serving and for getting up in the morning and understanding what you do has an impact on others,” she said. “I’ve always felt my skills and abilities have been a gift to me that you don’t waste. My faith gives me that sense of vocation, that sense of calling and purpose of serving others for the greater good.”

Now that service comes in the form of administering COVID-19 vaccinations at a clinic that runs 15 hours a day, seven days a week. Tachibana said some of the first patients to receive the vaccine were residents of a long-term care facility across the street from the hospital, many of whom hadn’t left their rooms since March 2020.

“It’s joyous,” she said of administering the vaccine. “Every shot you put in someone’s arm, there’s this special feeling that you’re protecting one more person from this disease.”