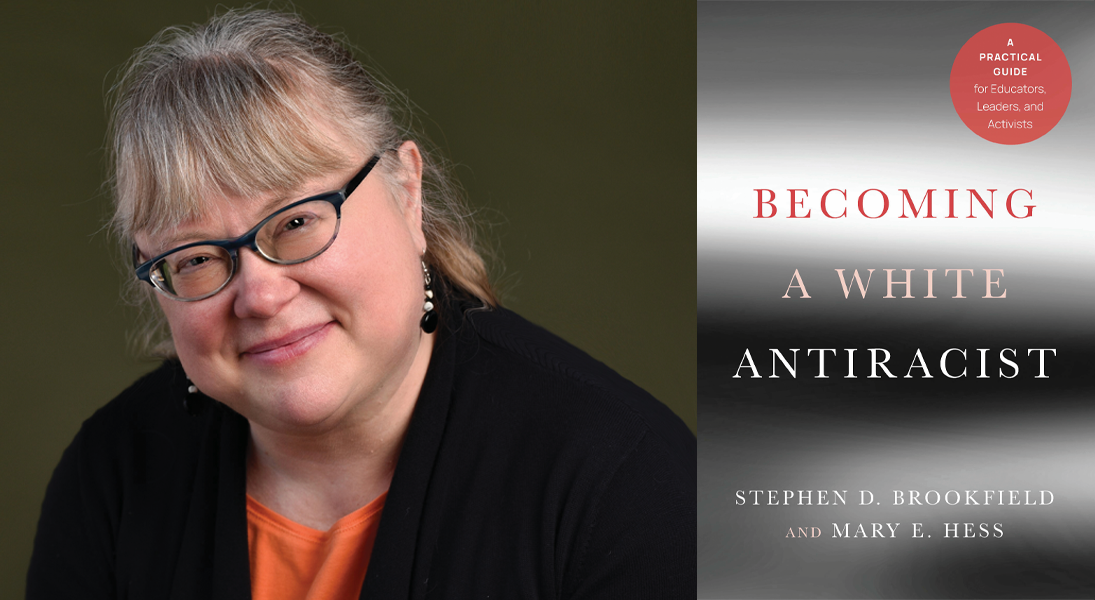

In Becoming a White Antiracist: A Practical Guide for Educators, Leaders, and Activists (Stylus Publishing, 2021), co-authors Mary E. Hess and Stephen D. Brookfield offer a road map for people of European descent who want to turn their awareness of racism and systemic injustice into action. Living Lutheran recently spoke to Hess, who has been on the faculty of Luther Seminary in St. Paul, Minn., since 2000, about how she and Brookfield aimed to create a resource for white readers seeking to create conversations about race, teach or arrange development workshops on racism, or help colleagues, students or fellow congregation members create an antiracist environment or culture.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell us about Becoming a White Antiracist?

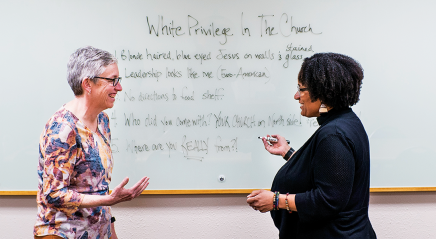

Hess: It’s about recognizing the ways in which we are all interconnected and [how] the brokenness of racism, and the whole process of racialization, has shaped who we are in the United States. As people of faith, if we are actually serious about recognizing that we are all one body, then [we must open] ourselves up as white people to the awareness of what has happened.

One of the things that we say in the book a lot is that, for a white person to do anti-racist work, you’re either going to do it imperfectly or not at all. So our desire was to try to find ways to at least do it imperfectly. The reason the book is called Becoming [a White Antiracist] is because we never actually get there—it’s a journey. And it’s work that needs to be collective as well as personal.

In the United States, a lot of [white] people have grown up thinking race is an issue for other people and that race is something that white people don’t need to think about. I think it’s almost the exact opposite: Those of us who are white benefit from the system to such an extent that it’s really up to us to change it.

What motivated you to write the book?

Stephen [Brookfield] and I were trying to do something that was very practical. There are multiple chapters in the book where we point to short YouTube videos and other kinds of resources that live in digital spaces that people can draw on—creative exercises, ways to hold conversations. At the heart of it, for me at least, is, what does it mean to be in accountable and authentic relationship?

Figuring out how to heal, to begin to restore and repair, those are impulses that are deep in Christian faith.

There are a lot of ways in which we are beginning to recognize—certainly here in the Twin Cities, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder but, I think, even before that—how broken and fractured the fabric of our relationships is. Figuring out how to heal, to begin to restore and repair, those are impulses that are deep in Christian faith. And Lutherans have something really powerful to offer. When Lutherans say we are simultaneously saint and sinner, that’s a powerful thing for a white person to say—to say, “I recognize that I live in a racist system.” So, rather than denying that [we] contribute to that …, we could say, “We get that we are implicated in the system. … What does that mean? How do I deal with that?”

How does your faith shape your approach to anti-racist work?

In Christian faith, we talk about a God of abundance, we talk about a God in whose love we are all drawn, and that love draws us toward each other. And one of the things about seeing racist structures is understanding how they have stopped us from following that love.

For me, this work grows deeply from my faith. I don’t know how to do this work without being nourished by a God who draws you into relationship. That’s what gives me hope and it’s what gives me energy and it’s what gives me a sense that healing can happen.

Are there things you think are especially important for Lutherans to understand as they engage in this work in their contexts, including congregational settings?

One of the things that’s interesting to me about the ELCA … is how deeply involved [members are] in things like Lutheran social services and all sorts of powerful and profoundly meaningful work that takes place that’s actually putting your feet on the ground and doing stuff. [But] there seems to be a disconnect of sorts between the work that so many Lutherans all over the country are doing and our worshiping spaces.

Congregations can ask bigger questions. They don’t have to ask, “Who’s not here on Sunday morning?” They can say, “Where should we be out in the community? Where is God drawing us out in the community?”

What are your hopes for your readers?

I want people to get energized and to feel like there are things we can do. … There’s not an endpoint, it’s something we’re constantly working on—and in working on it, there’s energy. It’s hard work, but it’s life-giving work.