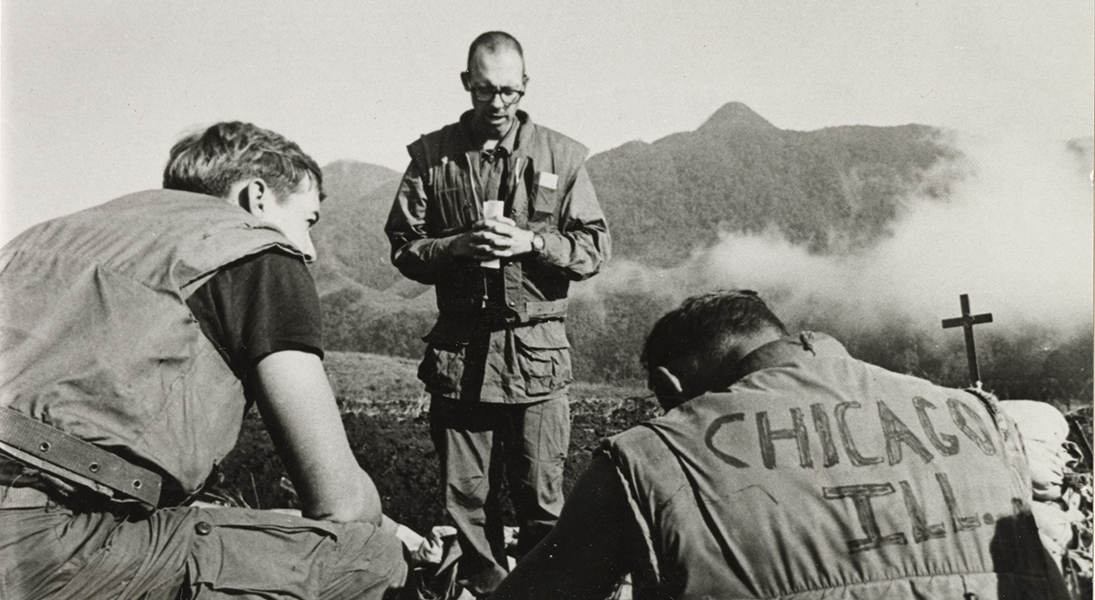

Instead of preaching inside pristine chapels, Ray Stubbe preached outside in foxholes. Instead of worrying about low attendance on Sunday morning, the 20-something chaplain conducted impromptu sermons to no more than seven at a time—mostly teens—who were hungry and a long way from home.

More than 50 years have passed since Stubbe, now a retired ELCA pastor living in Milwaukee, served as a Navy chaplain in 1968 during the Battle of Khe Sanh, the longest and deadliest combat of the Vietnam War. But, like many others who survived that monthslong confrontation, Stubbe often feels as if it happened yesterday.

Still dealing with the impact of his spiritual call, Stubbe believes it’s important to remember those who died as well as those still feeling the effects of that war, many from post-traumatic stress disorder. At the time, he was simply trying to be an effective spiritual presence for the other men in uniform.

“I felt a real sense of calling to go to Vietnam to basically be a friend,” Stubbe said. “I felt at the time that one proclaimed faith by living and not by words so much. It’s what you do that matters. I wasn’t the cool, professional chaplain in an office where people came to him to sort out their problems. I just wanted to be there as a friend.”

Stubbe was a few years older than most of the men serving, so some thought of him almost as a big brother, he said. He talked, preached and got to know them. He also had to help in times of crisis, including removing from a bunker the bodies of men who had died.

“I felt a real sense of calling to go to Vietnam to basically be a friend.”

This all took place thousands of miles from home and far from where his life had seemed to be headed.

Born in Wauwatosa, Wis., Stubbe had planned to attend St. Olaf College, Northfield, Minn., but instead joined the U.S. Navy Reserve in 1955 during his senior year in high school. He served two years’ active duty. “At that time, my minister told me I ought to join the ministry,” he recalled. “I don’t know why.”

After that, Stubbe did attend St. Olaf, where he earned a degree in philosophy, before moving to Luther Seminary, St. Paul, Minn. (then called Northwestern Lutheran Theological Seminary and located in Minneapolis). While there, he joined the Naval Reserve Chaplain Company and then attended the Naval Chaplaincy School.

Still, his career appeared headed in another direction. He was ordained in 1965, started All Saints Lutheran Church in suburban Milwaukee and then entered a doctoral program on ethics in society at the University of Chicago. Instead of staying, though, he volunteered for active duty, received a quick training for chaplains and was sent to Vietnam.

A ministry of presence

Though Stubbe had lost touch with many of those who served with him at Khe Sanh, he believed it important for veterans of the battle to have a way to communicate with one another, so in 1983 he formed the Khe Sanh Veterans Association.

“That group has continued to exist and even to grow,” he said. “But a lot of those people [at Khe Sanh] are dying or have died. … I founded [the association] and kept it going for the first five years. But I was aware that if an organization is going to exist for long, it needs a change of the leadership.”

Stubbe wrote books and essays about Vietnam and collected photos and artifacts, most of which he has donated to the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in Madison. He retired from the Navy in 1985 and began a ministry of visiting homebound people in Milwaukee.

At the time, Stubbe believed that “one proclaimed faith by living and not by words so much. It’s what you do that matters.”

While Stubbe prefers not to talk about himself, several people who know him believe his service to the armed forces shouldn’t be forgotten.

“He’s such a modest man,” said Brian Stamm, a captain in the Naval Reserve chaplaincy. “I said, ‘Ray, I think people in Christ would be strengthened by your story. And he said, ‘I’d be willing to do it if it helps others.’”

Part of that story is how Stubbe found a way to share his faith while in Vietnam. “When I was walking around from bunker to bunker, trench to trench, there were times explosions were happening all around me,” he said, “but I just knew that God was with me.

“As I was going around the base, I felt like I wasn’t representing God to people—but maybe I was representing God, making it clear that God cares about their welfare and is with them. That was more important to me than anything else I could say or do.”