Naomi Mbise knows what it’s like to move between places, spaces and cultures.

Mbise grew up in Tanzania but now finds herself on the campus of California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, as an International Women Leaders (IWL) scholar. IWL—an ELCA initiative that provides education and training opportunities to women from around the world—offers her not only the chance to experience a different culture but the opportunity to study how such adjustments transform young people.

A junior double-majoring in political science and in theology and Christian leadership, Mbise has always been curious about cross-cultural exchange and how it can both enrich and challenge young people. At age 9 she began attending a Seventh Day Adventist boarding school, a faith context markedly different from the one she’d known as a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania. Navigating these two worlds, Mbise said, showed her how experiencing different faith practices can lead to better understanding one’s faith.

Mbise began observing the ways in which missionary children in Tanzania had to move between cultures on a daily basis. She started seeing the many layers of our cultures—societal norms, family structures, faith practices, music, food. “No one culture has all the answers,” she said. “There are positives to take from each one. I can see what the West has and what my African culture has and integrate them together to help us grow into our best possible selves.”

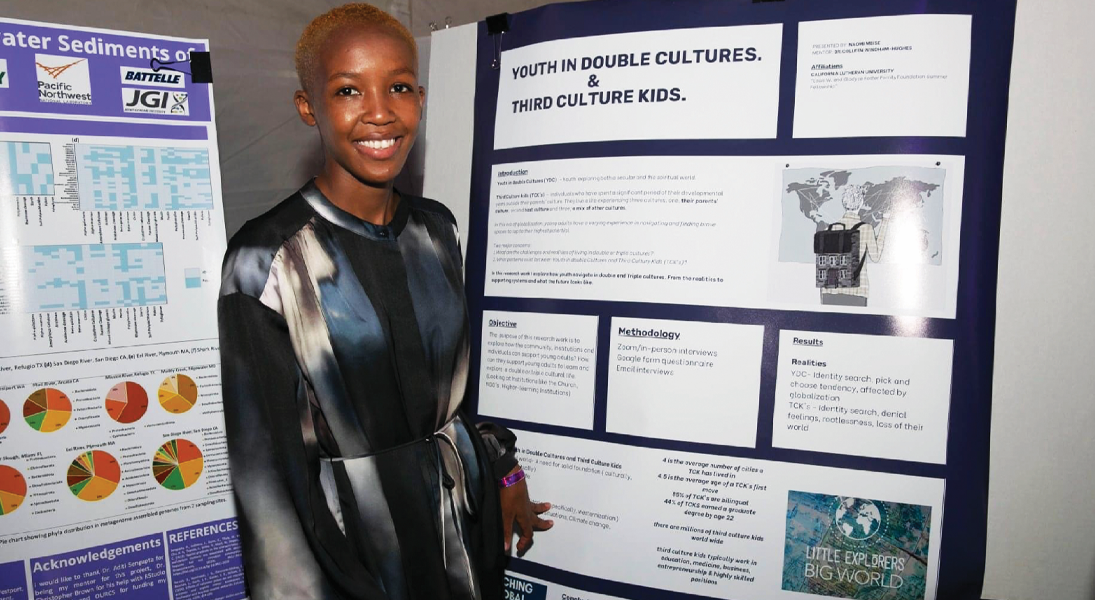

When Mbise arrived in the United States to study at Cal Lutheran, she was faced with another multicultural formation experience. But this time she wanted to study it. With the university’s support, she spent summer 2021 immersing herself in a research project titled “Youth in Double Cultures and Third Culture Kids.” Through her research she began to uncover the various ways young people navigate multiple cultures and how those experiences are carried into adulthood.

In our globalized world, young people’s experiences are driven by connectivity and cultural exchange.

As part of her project, Mbise examined both youth in “double cultures”—the secular and spiritual worlds—and “third culture kids,” a term coined by sociologist Ruth Hill Useem to define individuals in their developmental years who have spent a significant amount of time outside their parents’ culture. “They live a life experiencing three cultures,” Mbise wrote in her project—their parents’ culture, the host culture and a mix of other cultures.

Mbise interviewed adults who were raised as immigrants in the United States but felt they were unable to articulate their experiences growing up. She came to believe that providing young people with a platform to share such experiences is paramount to developing a society that can nurture them.

Now Mbise hopes her research will initiate conversations on the subject so that communities and institutions, such as the church, can better support double-culture and third-culture youth.

“Doing coursework in children, youth and family ministry, Naomi was drawn to bi-vocational and cultural translation across spheres of life,” said Colleen Windham-Hughes, a professor of religion at Cal Lutheran and one of Mbise’s mentors. “Her research can help churches expand the capacity to receive and welcome our neighbors.”

Mbise has found that, in our globalized world, young people’s experiences are driven by connectivity and cultural exchange, which afford them formation from a vast array of contexts. This type of multicontextual formation requires both openness and the ability to adequately process what one is experiencing.

“I feel like this generation of young people [is] very open to our multicultural world,” she said. “They are shifting as the world is shifting.”

Mbise believes that if the church truly wants to move into a new era of growth and connection with youth, it must become truly welcoming—not only to people but to their diverse ideas, experiences and cultural contexts.

Mbise concluded from her research that churches and other institutions can play an active role in helping young people navigate these new realities so they feel equipped to share their experiences with the world. She believes that piecing together a more complete picture of multicultural youth in our ever-expanding world is a way to ensure that young people’s experiences are not only heard but lifted up and valued.

“Youth development in double and third cultures is not a one-person job,” she explains in her project. “Families, the community, the church and primary caregivers all play a very important role in spiritual development.”

Mbise said the feelings of isolation reported by many young people today mean that they seek opportunities to connect with communities. She believes that if the church truly wants to move into a new era of growth and connection with youth, it must become truly welcoming—not only to people but to their diverse ideas, experiences and cultural contexts.

“Learning how to adapt to new things, new cultures and new experiences in order to better carry out God’s work in the world needs to be the focus of the church,” she said.

This, she added, is something the church can learn from third culture kids—and young people in general.