Series editor’s note: Throughout 2022, “Deeper understandings” will feature biblical scholars sharing some of their favorite books of the Bible. —Kathryn A. Kleinhans, dean of Trinity Lutheran Seminary at Capital University, Columbus, Ohio, on behalf of the ELCA’s seminaries

I am endlessly fascinated with the Letter of Paul to Philemon in the New Testament. The letter is very short, but there are so many different details that matter enormously when we try to tell its story. Some of these details are things interpreters have brought to the text, and some are things the text omits. But they all fuel our imaginations, and sacred imagination is the only way to make sense of this letter.

First, who wrote it? The answer may seem obvious: Paul did. But the details make the story more interesting. Verses 1-2 read as if Paul and Timothy wrote the letter together, but by verse 4 the letter switches to first-person singular: “When I remember you in my prayers, I always thank my God.” Then, in verse 9, comes this strange statement: “I, Paul, am writing this with my own hand.” Wasn’t Paul writing the letter all along?

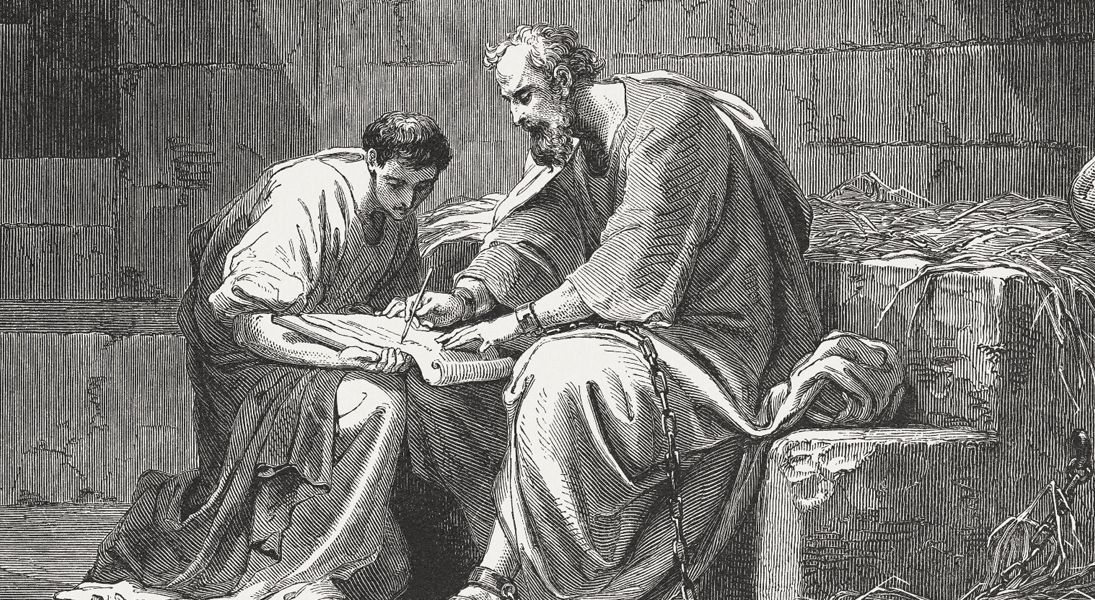

Paul’s letter, physically written by an enslaved person, was also written to enslaved people in the church.

One historical detail absent from the text: physically writing something wasn’t a skill every “writer” in antiquity had. Most writers spoke their words out loud to an enslaved scribe who knew how to mix ink, make pens and draw letters in the correct order on paper. Maybe Timothy was the scribe for this letter, but we know Paul used other scribes (Romans 16:22). Knowing this historical fact, we can imagine Paul awkwardly taking the pen from the scribe, writing a few words, then handing the pen back. They’re Paul’s words, but he wasn’t the only person who shaped the letter.

Another important detail is whom the letter addresses. Verses 1-2 address Philemon, Apphia, Archippus and the church in their house. This letter is written not to one person but to a house church—a household that welcomes other Christ-followers.

Whenever Paul’s letters mention a whole household of people, we can assume that enslaved people were part of that household. Enslaved people were everywhere in the ancient world. Even the lowliest tradespeople enslaved a person or two—and many owners hired their slaves out to others. So we can imagine that Paul’s letter, physically written by an enslaved person, was also written to enslaved people in the church.

Who was Onesimus?

A third detail is the matter of Onesimus. The letter negotiates for his return to the community, pleading on his behalf. Paul, in his own handwriting, offers to pay any debts Onesimus carries. The letter tells us that Onesimus is enslaved, not just in verse 16 but also in the meaning of his name—“Useful One.” Here is where missing details matter most.

We know very little about why Onesimus was away or why Paul was sending him back with this letter. Some commentators speculate that Onesimus was a runaway slave. (The letter is even quoted in the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 to justify the brutality of slavery.) The letter never suggests that Onesimus was trying to get away from the community, though interpreters assume as much.

Some interpreters take the master’s point of view and presume ill intent or dishonesty on Onesimus’ part—some wonder if he stole from Philemon and that is why Paul pays his debts. But adding these details reveals the interpreter’s biases—enslaved people are lazy, deceitful or ungrateful; masters are kind and benevolent and know best how to care for them. These are common stereotypes about enslaved people and enslavers. But why must Onesimus’ story be told only through the lens of those who could not, did not and would not imagine freedom for him?

Why must Onesimus’ story be told only through the lens of those who could not, did not and would not imagine freedom for him?

What if the details our imaginations added were from Onesimus’ perspective? Perhaps slavery was so intolerable that Onesimus was willing to risk everything for the chance to escape. If that is the case, we find ourselves in a very uncomfortable imaginative space. The letter is clear that Onesimus will return to the community. But why would Paul want to return to the community an enslaved person whose life was miserable enough for him to risk flight?

Some might suggest that Paul’s plea to the community to treat Onesimus as a beloved brother was heeded and that everyone lived happily ever after. But we know from our siblings in Christ who experienced slavery in the United States or live with its legacy that “happily ever after” isn’t possible as long as slavery and the impulse to dominate still exist.

Sometimes, living with the uncomfortable details of our Christian Scripture can free our imaginations to read the Bible beyond our own experience, wrestle with its tensions and love more freely the neighbors in our world who call for justice.