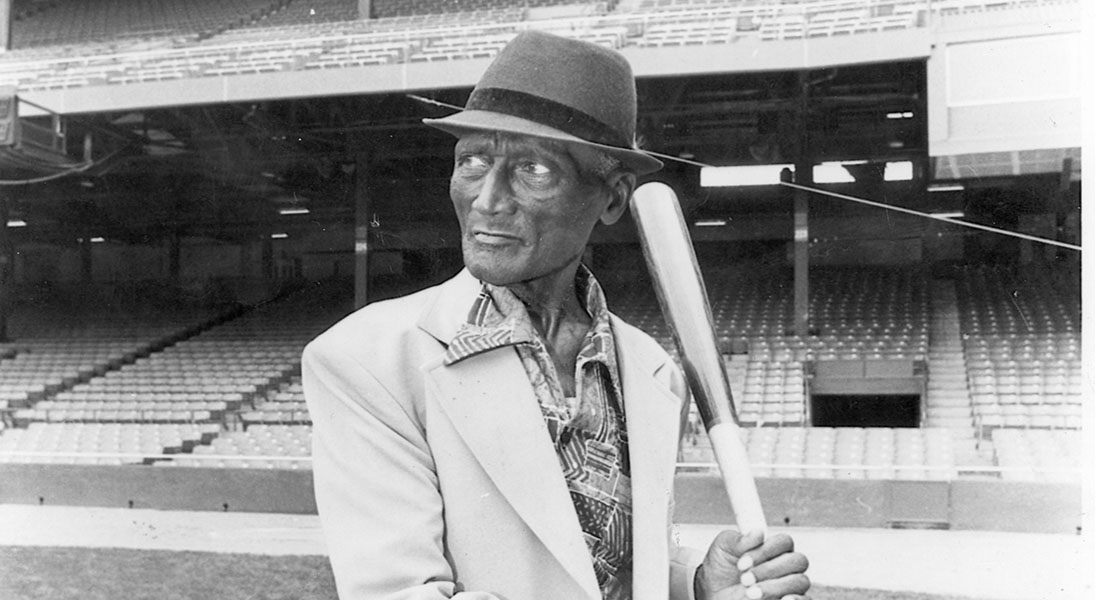

Across 18 years in the Negro Leagues, Norman Thomas “Turkey” Stearnes parlayed power and speed into enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

But his daughter Rosilyn Stearnes-Brown, the choir director and organist of Amazing Grace Lutheran Church in Warren, Mich., is just as impressed by what her father achieved through force of will as an older-than-average schoolboy.

“He was a big believer in education, but he had to drop out of high school to help his family after his dad died,” said Stearnes-Brown, a professional musician and retired teacher for Detroit Public Schools. “But he went back and graduated high school at 21.”

Stearnes-Brown shares her father’s many accomplishments in her book Fans Called Him “Turkey,” I Called Him Dad: A Daughter Remembers Baseball Hall of Famer Norman Thomas Stearnes (McFarland Books, 2022).

“He was a great all-around man with a great personality,” she said. “He loved people, and he never had a bad word to say. Some people thought that because he was quiet he didn’t have much to say. But he did—he just chose his moments carefully.”

Stearnes retired from baseball in 1940, seven years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball (MLB), and died in September 1979 at age 78. His nickname arose either from his distinctive running style, with arms flapping like a turkey’s wings, or, as Stearnes himself told it, because of the potbelly he had as a child.

The recognition they deserve

A 5-foot-11, 175-pound center fielder, Stearnes played primarily for the Detroit Stars in a career that began in 1923. It wasn’t until almost 100 years later, in 2020, that MLB announced that it was officially “correcting a longtime oversight in the game’s history” by recognizing the Negro League players as major-league caliber and including that league’s statistics as part of the sport’s record and history.

Stearnes played in 986 league games (not including barnstorming tours and other exhibitions) and batted .349. A five-time All-Star, he is credited with a Negro League-best 186 home runs and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 2000.

Born in 1946, Stearnes-Brown learned of her father’s baseball exploits by listening to front-porch conversations between Stearnes and legendary pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige, and also from a maternal uncle who starred in the Negro Leagues, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe.

“The players in the Negro Leagues were great men in baseball and in their personal lives,” she said. “You would have thought that with all that they endured, all of the prejudice, that they would have been bitter, but they did not concentrate on the negative, only on the positive that they could do.”

“I wish it would have been done for them while they were still living, but I’m glad now they’re recognized as major leaguers.”

Lutheran roots

Describing her father as a humble, generous, gracious and dependable man of faith, Stearnes-Brown said her family’s Lutheran roots trace to her maternal grandmother, Olga McArthur.

When Stearnes-Brown was 4 years old and her sister Joyce was 3, the girls went to Birmingham, Ala., to live with their grandmother for two years while their mother, Nettie Mae, underwent treatment for an intestinal blockage.

McArthur’s love of music rubbed off on the girls as it had Nettie Mae, who would play the piano in the Stearnes home while Turkey and his daughters would sing as a trio.

Both Rosilyn and her sister—Joyce Stearnes Thompson—sing professionally with the renowned Brazeal Dennard Chorale, based in Detroit. For the past 13 years the sisters also have been invited by the Detroit Tigers to perform the national anthem at Comerica Park during the team’s annual celebration of Negro League baseball. This year they also were asked to sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” commonly referred to as the Black national anthem.

“Rosilyn is just a remarkable person,” said friend and Amazing Grace member Sandy Burgess, citing her “massive musical talents and the strength of her faith.”

“She is such a blessing to our congregation and our whole community,” said Burgess, who assisted Stearnes-Brown with Fans Called Him “Turkey.” “This is a remarkable story that she’s told. She put her heart and soul into writing it.”

“A celebration of diversity”

Susanna Muzzin, pastor of Amazing Grace, describes the book as a story of perseverance, resilience and excellence, as well as a celebration of diversity.

“He just sounds like a wonderful, wonderful man—and I can personally attest, knowing his daughters, what a great father he must have been,” Muzzin said. “Our church is 100% behind Rosilyn, cheering her on. We’re a real community, and Rosilyn is such a fundamental part of that community.”

And though it came two decades after her father’s death and long after his playing days, Stearnes-Brown is thrilled that pioneering ballplayers of African descent such as her father have finally been welcomed into the MLB community.

“I wish it would have been done for them while they were still living, but I’m glad now they’re recognized as major leaguers,” she said. “Dad and Double Duty are finally getting the recognition they so deserve.”