Editor’s note: In this article, the terms Anishinaabe, Ojibwe and Chippewa are used interchangeably. To learn why, visit whiteearth.com/history.

For some the concept of “reparation” is a troubling one. How can it be done? What is fair and equitable? It involves money and grappling with history, which makes it a complex and emotional topic, one that many individuals and organizations shy away from. For the leaders of the Northeastern Minnesota Synod, it was just the next step in a yearslong commitment.

On Oct. 6 the synod announced that it would give $185,400 plus $100 plus $1,100 to the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, which includes leadership from the tribe’s six reservations (White Earth, Bois Forte, Grand Portage, Mille Lacs, Fond du Lac and Leech Lake), as an act of reparation. “This number has meaning,” Matt McWaters, chair of the synod finance committee and pastor of Hope Lutheran Church in Walker, Minn., declared on the synod’s Broken Lands podcast. “It has meaning for our shared narrative in this place with our Native American neighbors.”

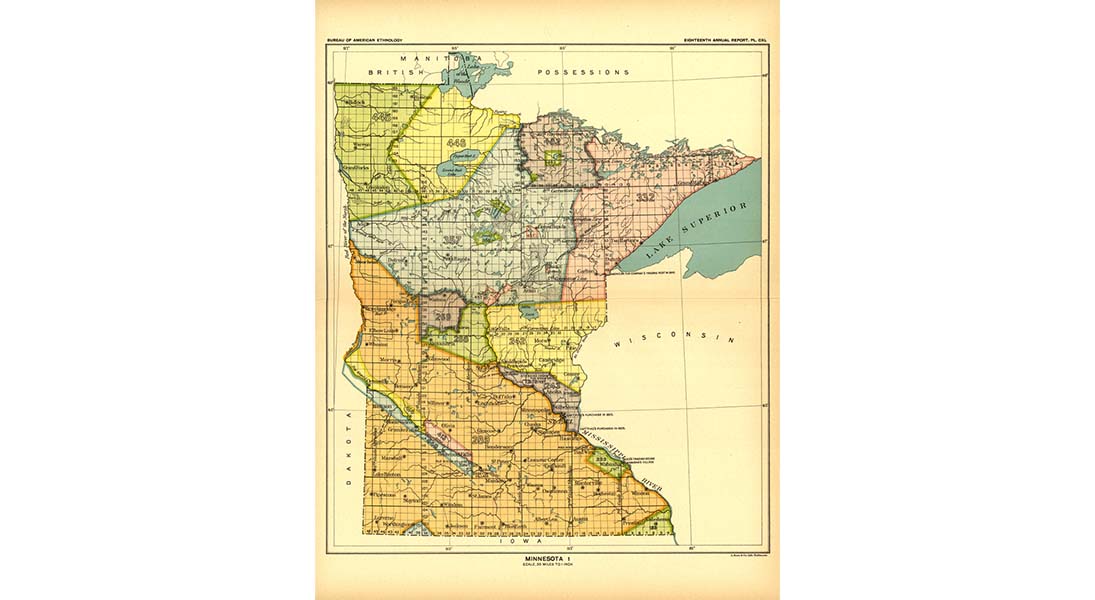

In 1854, 1855 and 1866, treaties were signed between the Anishinaabe and the federal government in which the tribe ceded nearly 10 million acres of land in Minnesota and Wisconsin. The years of these treaties coincide with the reparation made by the synod: 1854(00) plus 1(00) year plus 11(00) years.

Colleen Bernu, the synod’s director for evangelical mission and minister for diversity, equity and inclusion, said, “Our hope was that [the number] would be meaningful to the tribal community and that it would encourage people who may not know the story to say, ‘What is with this figure?’ And that’s exactly what it’s done. It’s provided the opportunity for us to say, these are treaties by which you are allowed to build the community that you live in.”

“Deep learning leads to a commitment to building a relationship, and it’s all about the relationship.”

The synod’s initial press release described reparations as “re-pairing: a bringing back together that which was violently separated.” For Bishop Amy Odgren, “re-pairing” begins with listening. “We have a lot to learn about storytelling,” she said. “Storytelling with us being the receiver and listening. When we learn story, we start to see one another in each other’s stories, and I feel like that’s the beginning of the relationship.”

As far as actually giving the money to the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, the synod didn’t want accolades or notoriety. “There was absolutely no ceremony,” Bernu said. “There was absolutely no pomp and circumstance. This was a gift given with a commitment to start re-pairing the broken relationship and breached trust. The check was presented between Bishop Amy and President [Cathy] Chavers at dinner.”

Odgren said the dinner with Chavers, president of the executive committee of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe and chair of the Bois Forte Reservation, was “just a fun meeting.” They immediately connected over a shared fashion sense and the experience of being grandmothers. Odgren shared the work the synod had done and its hopes to return land to the tribe in the next few years. They both committed to more frequent conversations over dinner. “We had all these connections with each other, and I think that’s what happens when you build a relationship,” Odgren said.

The reparation from the synod was welcomed by the tribe, which voted unanimously to accept the gift at its Oct. 28 executive meeting. Gary Frazer, executive director of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, expressed gratitude and shared that the leadership discussed how they might use the gift “to help our children currently in foster care to be reunited with their families.”

He added, “We appreciate the honesty that the Lutheran church has shown for the past mistakes that were made and look forward to a closer relationship in the future.”

“Know your context”

Reparation is a big conversation happening all over the country, including in our churches. Bernu, a direct descendant of the Osaugie Community in the Fond Du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, shared some thoughts about churches and synods wanting to make reparations to Indigenous communities: “Know your context. Understand the culture and the community of the Indigenous people with whom you plan to enter into this work. Understand the priorities of that community and what’s important to them and what feels like reparative work for that community.

“For us, to do a reparation or a land return without relationship and a commitment to figuring out how to live well together going forward would’ve been just an act.”

Odgren added, “Deep learning needs to happen before you rush into a reparation. Because that deep learning leads to a commitment to building a relationship, and it’s all about the relationship.”

Synod leaders plan to continue to live out their commitment to building relationships with their Ojibwe neighbors. “It’s a beginning,” McWaters explained. “It’s not the last step. We are just starting to find our place here together and to write this narrative together again.”

Listen to the Broken Lands podcast.