Editor’s note: This post was originally published on the ELCA Racial Justice blog.

I was 4 years old when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. I was too young to understand the import of his words while he lived. Yet I remember the importance of those words, his struggles and his assassination to the Black community as I grew up in Chester, Penn. The community felt he was one of theirs. Not only was he a marvelous young African American preacher and civil rights leader, but he was also educated at Crozer Theological Seminary, just up the road in Upland, Penn.

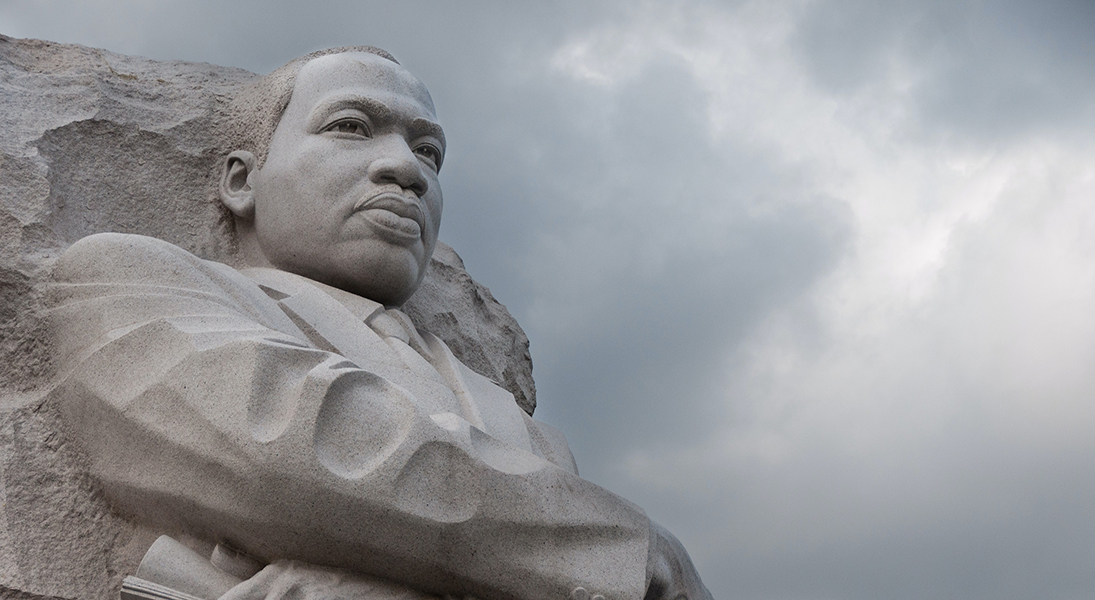

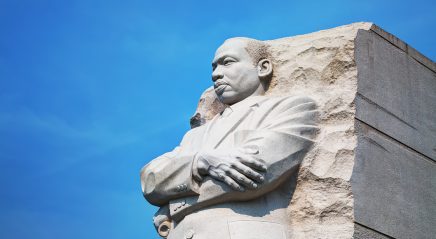

In the late 1960s and ’70s a framed picture of the civil rights leader hung in almost every Black home—at least in every one that I entered. His picture hung in a prominent place in Granny Bettie’s kitchen. There was a picture in Granny’s best friend’s home, in my Aunt Lucille’s home and in all the homes of my family members. King’s words and legacy were celebrated in our community long before his birthday was designated a national holiday.

Many in the community took to heart the words he preached, the speeches he made. I especially remember hearing the words, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character” on my grandmother’s television. I sat on a stool in a corner of the kitchen as Granny and her friends sipped instant coffee and talked about the possibilities. What would it look like for Blacks to be seen as brilliant and beautiful and capable—as equal to whites? My granny wanted King’s words to be true for me and my siblings.

After all these years, mothers of Black children still worry about how their children are perceived.

Granny Bettie was born in the 1920s, when Calvin Coolidge was president. She grew up in the South at a time when grown men were referred to as “boy” and grown women could only be “gal.” Her mother, whom I called Grandma Essie, was the daughter of a slave. My granny picked cotton when she was a young girl and had only a sixth-grade education. When she moved north, she did domestic work. Often referred to as “gal” well into her 50s, she did not know what it was like to be judged by the content of her character.

When Barack Obama was declared the Democratic nominee for president, many believed that King’s words had come true. I was so hopeful and yet afraid to believe. Some 45 years after MLK’s speech, on the night of the 2008 election, I sat alone watching the results. When Obama was declared president-elect, with tears in my eyes, I thought, “I wish Granny were here to see this.”

The community was so hopeful; I was so hopeful. Many would say that as pastor of a white congregation, I am evidence of the dream becoming real. Yet at the dawn of 2023, King’s words have yet to be realized. After all these years, mothers of Black children still worry about how their children are perceived. I worry as my 16-year-old grandson gets his driver’s license, as he travels with his track team, as he walks in this world; will the prayers of his pastor-grandmom be enough to keep him safe? My grandson stands six feet tall and has an athletic frame, and though he has a baby face and the cutest dimples, I do not know if he will be judged by the content of his character or be thought of as a threat because of his beautiful brown skin.

My prayer for all children in 2023 is that Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream will soon be their reality.