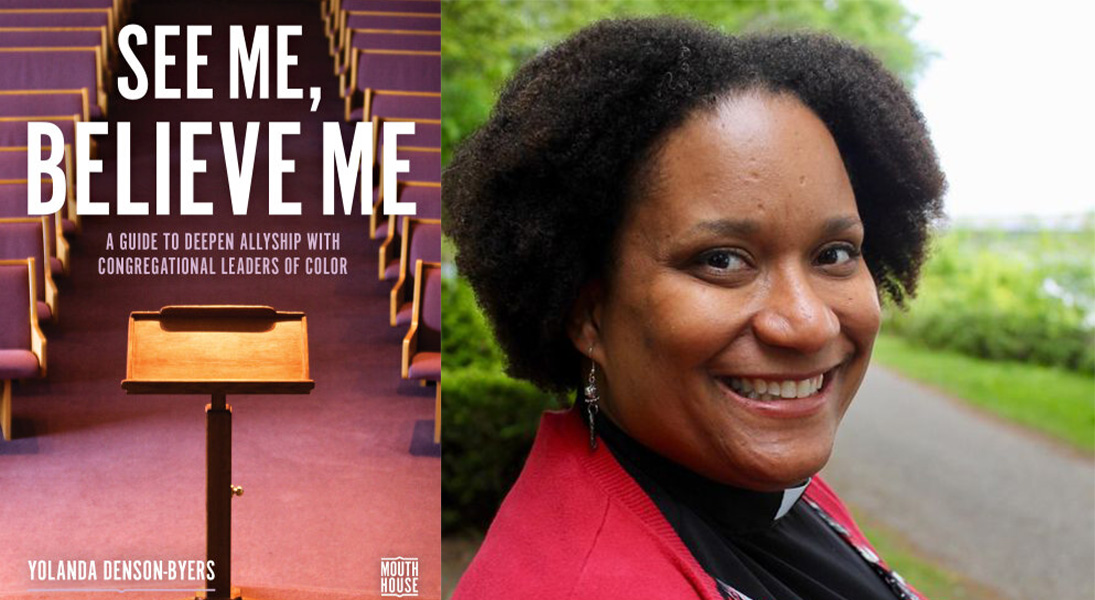

In her new book See Me, Believe Me: A Guide to Deepen Allyship With Congregational Leaders of Color, Yolanda Denson-Byers describes two kinds of wounds often experienced by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) leaders serving in predominantly white churches. The first wound comes from outwardly hateful behavior directed at them all too often in the church. The second occurs when their supposed white allies don’t believe them when they share their experiences.

See Me, Believe Me offers the stories of these hurtful incidents and patterns of behavior experienced by Denson-Byers—pastor of Shepherd of the Hills Lutheran Church in Edina, Minn.—and other leaders, as well as discussion questions and next steps for readers in living out true allyship to their BIPOC congregational leaders and taking anti-racist action in their contexts.

Living Lutheran spoke with Denson-Byers about See Me, Believe Me, part of Augsburg Fortress’ “Mouth House” series and a follow-up to Call to Allyship for readers continuing their allyship journeys.

Living Lutheran: Could you tell readers about See Me, Believe Me?

Denson-Byers: See Me, Believe Me is a guide to successful relationships with BIPOC leaders in the church and elsewhere. Frankly, I believe it would be beneficial for any European American to read if they want to be in any kind of relationship with a person of color. At the end of each chapter, there are practical steps one can take to enhance allyship.

It is also a storybook. In it, I and other BIPOC leaders share authentically about the racism that we have faced in the church. I have found that white folks often want to minimize the reality of racism in our congregations, but these stories make it clear that there is much work to do together to rid ourselves of this grievous sin, both in the individuals and institutions, that make up the church.

As you said, the book highlights your own experiences in ministry, as well as others’. What was the process of synthesizing these stories like?

Dawn Rundman, my editor, allowed me to write as I saw fit. I wrapped the practical application around the stories that I knew I needed to share. I put out a request to BIPOC leaders I respected, inviting them to interview with me. Most of them were willing to do so. I was honored because I know that we often don’t have capacity, or the emotional “spoons,” for these types of conversations on top of the work of being a pastor in the ELCA.

The BIPOC folks in your life don’t have the privilege of only doing anti-racism work when it is convenient. For us, it is often a matter of life and death.

Our BIPOC leaders are amazing! No matter how exhausting it is to tell our stories and to continually be teaching, most of us are willing to do so in an attempt to make things better for those who will come behind us. I’m so grateful for the elders who blazed a trail for me, and I feel compelled to do the same for others.

Here, I would like to encourage actively anti-racist white folks to do the same. There are those who need to follow in your footsteps as well. My book encourages white folks to persevere, even when it is hard or uncomfortable. This is because the BIPOC folks in your life don’t have the privilege of only doing anti-racism work when it is convenient. For us, it is often a matter of life and death.

There is a trauma involved in reliving and sharing the experiences you cover in the book. But you also describe the catharsis and healing it sometimes afforded. Could you describe the experience of writing the book?

For myself and other BIPOC leaders, the hardest thing about serving in a predominantly white church is that the trauma is never a “one and done” type of thing. Even as we are trying to recover from one egregious incident, another one occurs. So, it is not something that we can talk about as history. It is something that we experience in the present, on a recurring basis.

Recently, an [older] white male questioned my credentials for administering my congregation as the senior pastor. Despite almost 29 years of pastoring, in many different contexts, [a Master of Divinity degree] from Harvard University and a doctoral degree in congregational mission and leadership, he felt he had a right to do this. It is astounding that this happens to me and others on a regular basis in our church. I recently saw a meme on Facebook that said, “If you wanted me to talk about you better, you should have treated me better,” and I felt that in the depth of my soul. My story is mine to share and I will do so with impunity. This is a part of what healing looks like for me.

Many readers may come to the book thinking of themselves as allies. But you suggest that if one’s allyship has never caused them discomfort, dissociation or pain, theirs isn’t a true allyship. Could you say more about what being a faithful ally looks like?

Someone once said to me, if you’re not standing close enough to your BIPOC friends to be hit by the stones hurled at them, you are not actually an ally. In other words, being an actively anti-racist individual is costly work. If one is never uncomfortable at the Thanksgiving table, water cooler at work or the annual congregational meeting, then it’s a good chance that you are offering “thoughts and prayers” rather than actions and behaviors that bring about real and lasting change.

We don’t need performative allies, we need real allies committed to change, no matter what the cost.

As BIPOC folks, we don’t need performative allies, we need real allies committed to change, no matter what the cost. One only has to look at the American civil rights movement to see white folks who were willing to put themselves, their bodies and lives on the line to change our nation. That’s what real allyship looks like.

See Me, Believe Me is written primarily to white members of the ELCA. But much of it is also applicable to other predominantly white churches and spaces. How do you hope readers, inside and outside the ELCA, engage with it?

The good thing about truth is that it is universal. Not only would this book be applicable to other denominations, but I believe it contains wisdom and information applicable to any space where people of color work and live. I hope that people will read the book and utilize the parts that are applicable to their life experience.

In the Black community we say, “Eat the meat, spit out the bones.” In other words, take what you can use and leave the rest. While it may not all apply to your life experience, some of it will. Not only that, but I hope that people will share this book with friends, family, neighbors and colleagues, using it to open up courageous conversations with folks who may not otherwise do so. It’s my experience that many white folks—particularly in the ELCA—want to know and do better, but don’t have the slightest idea where to start. This book could serve as a starting place for many people.

I am grateful to those who are reading and sharing my work. Together, with the leadership, inspiration and equipping of the Holy Spirit, we can bring about positive change for us all. Anti-racism work is not just done to enhance the life experiences of our BIPOC neighbors. It is necessary soul work for white folks as well.