When you think about technology in the church, does projecting song lyrics onto a screen for worship come to mind? Or is it something bigger in scope—like a live Twitter conversation discussing real-life events and how they tie into faith?

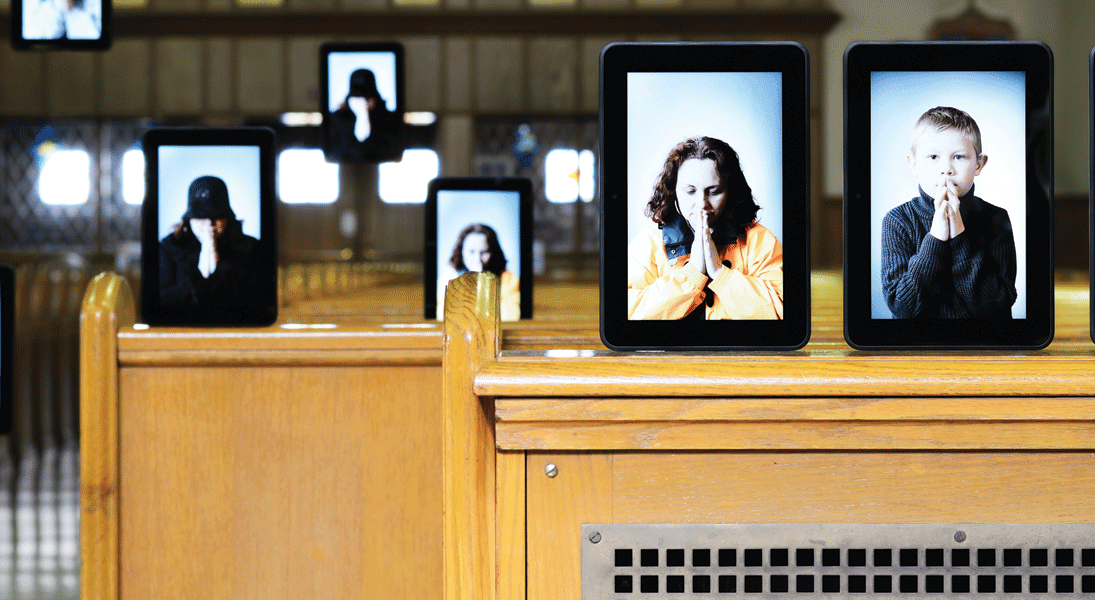

In today’s digital age, ELCA communities are experimenting with new worship formats as congregants embrace innovative ways to form faith groups, often in ways that look nothing like the church of the 20th century.

Take the Slate Project. Founded as a mission of the Delaware-Maryland Synod by Jason Chesnut, an ELCA pastor, and Jenn DiFrancesco, a Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) minister, the project is what they describe as a “radical” movement to reimagine the church.

“A lot of the online content I had seen … was trying to get people to go to a church, with livestream services, free Wi-Fi, ‘Come to our worship here!’” said Chesnut. “I was sitting at Starbucks, and everyone online was on Facebook,” he said. “[I thought], ‘I want to be there. I want to create content that they can see while they’re scrolling.’”

Many people have been to churches that bored them, abused them or told them they’re not worthy, Chesnut said. The project name came from a question he asked: “If we could start Christianity with a blank slate, what would that look like?”

Although based in Baltimore, the group exists entirely online, using the Twitter hashtag #SlateSpeak for a “progressive Christian tweet chat” on Thursday evenings; the hashtag #SlateReads for a live book club discussion on Wednesday evenings; weekly images posted on Facebook to engage 21st-century Christians; and a monthly video and podcast.

“The way things have been done the last two or three generations in the church doesn’t make sense now.”

“The way things have been done the last two or three generations in the church doesn’t make sense now—[this belief that] the only way to be churched is to go to a building and have worship on Sunday morning and have confirmation and Bible study and that’s it,” Chesnut said. “It’s not bad; I’m just saying, we’re doing small things to try to make the church more interesting.”

One way the Slate Project aims to keep things interesting is by broaching topics that might typically be seen as controversial or sensitive in many churches, including pop culture, politics or relevant real-world tragedies. An online platform can be a more comfortable space to contemplate and discuss such issues, said Chesnut.

“There are certain things I can type and I can text that I cannot say in a conversation because I’m not comfortable or it wouldn’t be received well. But I can [type] it on Twitter and take my time and say it in a way that’s meaningful to me,” he said.

While an online presence is the backbone of the Slate Project, the group hosts a weekly dinner liturgy, #BreakingBread, at the Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation in Baltimore. It also hosts #WakeUpWordUp, a weekly Bible study hosted at a local coffee shop.

“We’re using the technology of our day to supplement the institution,” Chesnut said. “There’s this amazing world out there. We’re unbelievably connected, [like] no other generation has been. We’re trying to take advantage of that.”

Reaching new people

Digital technology can also be a crucial avenue for the church to reach people who have previously been, for a variety of reasons, unreachable.

Staying connected with people from foreign countries, for instance, is much easier with online platforms than it has been in decades past.

“We have partnerships with congregations in El Salvador and Tanzania,” said Danielle Miller, a pastor of Advent Lutheran Church in New York City. “There’s community that can be built digitally in those places when we can’t be there.”

But even on a local level, technology can bring together those who might not fit the mold of a traditional church service.

Advent hosts a weekly lunchtime Bible study in person, with the option of chiming in via Google Hangouts, a free text, voice and video chat service.

“We found that, [for] people here in the city, work hours are ridiculously long,” said Danielle Miller, a pastor of Advent. “And to get from one place to the next, the day is gone pretty quickly. But during lunchtime, [there’s] time for a break. Or, at-home parents have an hour during nap time. They can’t leave the kids, [but they can join us online]. … Some of our older members, it’s harder for them to get out of the house. And with Google Hangouts, it’s simple. They can call in by phone or call in with video.

“The reality is, people are incredibly busy, and their hearts are here, but their bodies can’t always be. We’re trying to break down barriers.”

Breaking down barriers is what ELCA pastor Joseph Castañeda Carrera set out to do in 2016 when he started ADORE LA in Los Angeles.

This synodically authorized worshiping community specifically reaches out to LGBTQ+ people of color, with digital communication a major component of its footprint.

“We’re trying to break down barriers.”

“So often in our church, we don’t have very many queer people of color,” Carrera said. “Community can’t build around them because we’re all spread out all over the place. … People from all over have joined [ADORE LA] because it’s creating a community that doesn’t exist in their own neighborhoods.”

Like the Slate Project, ADORE LA doesn’t have a physical address or building for worship. Instead, it connects with members via several digital means, including a weekly livestreamed, interactive video gathering, “Made by Prayer,” that focuses on challenging faith questions.

To connect with members on a frequent basis, ADORE LA utilizes GroupMe, a group messaging app that allows users to share texts, videos, images and documents. Instead of using email, ADORE LA sends group texts for reminders and as a way to organize documents.

“We actually don’t have an email list at all,” Carrera said. “It’s way more effective when we do text reminders.”

When ADORE LA does hold in-person gatherings—like Hike Church, a group hiking ministry that incorporates Scripture reading, conversation and communion at the summit—events are posted on Meetup, a social platform that helps people with similar interests connect.

“We post our gatherings there so people can find us that way, and they do,” said Carrera. “We’ve had a lot of our leaders come and say, ‘Why wouldn’t other churches post [their events]? Of course we want to find you. Meetup groups have hundreds and hundreds of people; people are so curious about churches that are willing to be in these different spaces.”

ADORE LA also produces the “Queer Faith” YouTube series, designed for LGBTQ+ people from across the country and from all walks of life to share life and faith experiences.

“Technology is one space where you get a really diverse cross-section of various cultures and living situations,” Carrera said. “It’s a real beautiful thing having people [from urban areas] do prayers about traffic, then have prayers about animals in rural areas suffering from floods. Those prayers don’t often come together, but … they sit before the same God.”

“There’s no secret”

Communities that have embraced new ways of interacting have a message for those wary of following their lead: You don’t have to be tech-savvy to join in.

#SlateSpeak, the primary ministry of the Slate Project, is a fairly simple initiative, Chesnut said. “We’re online Thursday, 9 to 10 [p.m.] Eastern; we start with prayer and have conversation around a specific topic,” he added. “That doesn’t require any tech-savvy, that just requires you to be on Twitter. There’s no secret to it.”

Carrera doesn’t consider himself a “techy” person. He simply downloaded several interface tools on his phone, then practiced until using them became second nature. “You can be such a quick learner if you click on a button [and] put aside that fear,” he said.

Age is no more a barrier than technological sophistication—you don’t have to be a millennial to embrace digital change.

In Montgomery, Ala., Tiffany Chaney leads Gathered by Grace, a synodically authorized worshiping community that intentionally serves those 18 to 40 years old. That demographic played a role in the congregation’s choice to use technology for hosting an online Bible study.

You don’t have to be tech-savvy to join in.

But Chaney, a bi-vocational pastor who serves as mission developer for Gathered by Grace and as a business development director at a Montgomery hospital cooperative, said she’s noticed something interesting in the hospital’s demographic data.

The hospital conducts patient surveys that can be completed either on paper or online. One of the biggest groups of online responders is 18- to 30-year-olds, which doesn’t surprise Chaney. But the 65- to 74-year-old group also generates a large email response.

“When I thought about that, it makes plenty of sense,” she said. “[Many in that age group] have just retired from the workforce. They’ve been working for decades with computers and are computer-literate; they’re using smartphones and are very comfortable doing so.”

Carrera doesn’t believe age figures prominently in people embracing technology. How we use technology in church has more to do with personal preference and how we wish to worship, he said.

“My grandfather is 89, and he has the latest iPhone and will engage in everything,” he said. “[Technology] is not bound generationally by ability … but I think it’s possible that specific generations will decide it’s not what they want their church experience to be. And that’s OK.

“[But] technology is always an undercurrent of how we live our lives. Whether or not you like traditional or contemporary music or contemporary worship styles, I think technology, for bringing in the world, is still important. Traditional or conventional church doesn’t need technology as much, but you won’t be encountering the world.”

Finding balance

On Tuesday evenings, members of Gathered by Grace meet for worship in person. But on Sunday evenings, they connect using Zoom, a popular videoconferencing service, for online Bible study.

“One of the things that sort of surprised me is [that] we ended up with a totally different set of people than the people who gather in person, so it allowed for a second community to form, which has been really nice,” Chaney said.

“Some people who are part of the online community live in other cities, an hour away. So it’s formed a community that’s not just geographically centered. … You no longer need to be within driving distance to experience community.”

While Chaney appreciates her online community, she has no intention of ever replacing face-to-face gatherings.

“At a certain point, you have to consider what is the mission of ministry,” she said. “I believe it’s important that we not forsake our being together in person. From a sacramental standing, we share the sacrament in our gathering meal. I value our in-person gathering, and I value our online gathering, and I think we use those forms of gathering in two different ways.”

Even the most pro-technology church leaders agree that person-to-person interactions are vitally important. It’s one reason Chesnut and DiFrancesco teamed up to form the Slate Project: Chesnut generates online content; DiFrancesco is the pastor on the street who coordinates gatherings.

The way to navigate technology, most agree, is to find balance.

The way to navigate technology, most agree, is to find balance.

Chaney intentionally chose Zoom as the digital platform for Bible study because it provides two-way communication, allowing all users to see and respond to each other.

Similarly, the mixed-medium Bible studies at Advent—hosted in person and through Google Hangouts—were specifically chosen to keep individuals as visually connected as possible.

“At Advent, we push for people to be present in the room and for their face to be present in video,” Miller said. “[Otherwise], you lose facial expressions, you lose opportunities to see the way your statements are landing. That’s a point of emphasis for Advent: let us still see you.”

Carrera feels similarly: “So much of pastoring is sharing the word and seeing the face and seeing reactions.”

He does so in person and digitally, through video chats. “We have all these beautiful ways to interact with people,” he said.

Budget impact

The utilization of technology can also have an enormous impact on church budgets, which many congregations struggle to balance.

Most of the apps that tech-savvy churches use on a weekly, if not daily, basis are free, said Carrera. That includes Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, FaceTime, GroupMe and even Zoom and Meetup, to an extent (the latter two charge fees for organizers or services beyond basic levels).

Carrera said he has saved potentially thousands of dollars by utilizing Canva, a free graphic-design tool website, to create images, posters and other graphics himself instead of hiring a designer or paying for an expensive software program he’d need advanced skills to navigate.

For faith communities without a brick-and-mortar location, costs are a fraction of those of traditional churches with buildings to maintain. And that may need to be the way churches operate in the future, said the Slate Project’s DiFrancesco.

“I don’t think [many] can afford to pay a pastor and keep these buildings,” she said. “Unless you have a major … endowment, you won’t be able to raise enough dollars.”

Eventually, future generations, including Millennials and Generation Z, may demand the embrace of technology—financially, socially and spiritually.